– By BRENT SNAVELY

Detroit Free Press

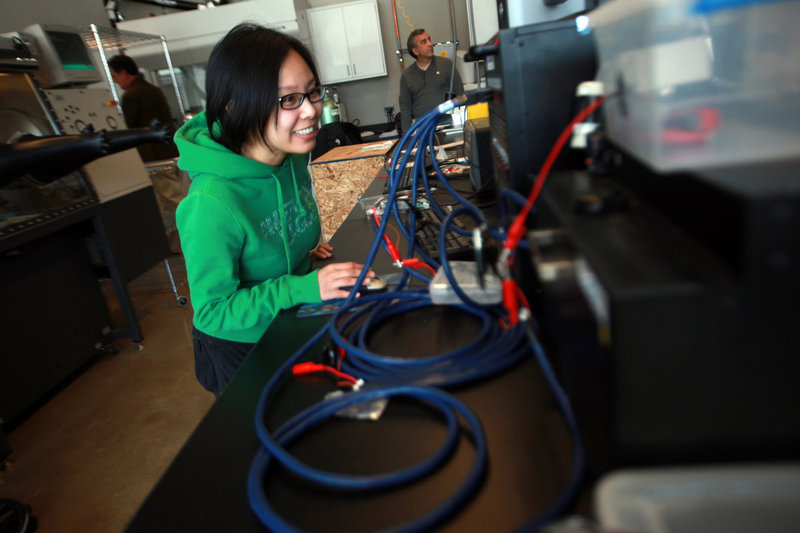

DETROIT – Engineering students and newcomers to the auto industry are unfazed by the deep job cuts and troubles the industry has suffered in recent years — especially those looking to become tomorrow’s electric vehicle engineers.

“Electric and hybrid vehicles are for the future — they can be for any part of the world — but also in the U.S.,” said Krishna Jasti, 24, a graduate student in Wayne State University’s electric vehicle drive engineering program.

Domestic automakers – on the cusp of emerging from nearly a decade of job cuts and market-share losses – are scrambling to fill thousands of engineering positions after shedding thousands over the past 10 years through job cuts and early-retirement offers.

GM, Ford and Chrysler are working with colleges and universities to develop courses to train and retrain the engineers who will be expected to develop tomorrow’s electric and hybrid cars and are trying to recruit from other industries.

But automakers face the challenge of recruiting people to join an old-guard manufacturing industry after years of job cuts and salaried buyouts.

“For me, it’s a minor bump right now. The industry has a long, rich history,” said Rhet De Guzman, 26, a Ph.D. student at Wayne State University. “I can see that this is a solid industry.”

This year, U.S. auto industry sales are expected to increase about 10 percent to 12.5 million. But that’s still a far cry from the 16 million or more sold annually for most of the last decade.

“I have confidence that the auto industry will come back,” said Rihong Mo, 50, who left General Electric’s locomotive division in November after more than 11 years with the company to lead a team of engineers at Ford. “This is the frontier of electric motors.”

That’s good news for automakers, said David Cole, chairman emeritus of the Center for Automotive Research in Ann Arbor, Mich., who has been warning of a coming talent shortage in the auto industry for years.

“There are a lot of companies looking for people with certain skill sets,” Cole said. “It’s creating a dilemma and it is just the start.”

De Guzman, who is from the Philippines, could have pursued an engineering career with the oil and gas industry.

Instead, De Guzman is trying to figure out how to improve the conductivity of lithium-ion batteries and hoping to work for the domestic automotive industry.

“When I was working in the refinery, I could see what it was doing to the environment,” De Guzman said. “So, I went from non-green to completely green.”

De Guzman is among the new engineers who view the auto industry as a place where fuel-efficient technology is advancing at a rapid pace and an opportunity to improve the environment.

And, after years of scaling back, General Motors and Chrysler are hiring 1,000 engineers each while Ford wants to hire engineers to fill many of the 750 salaried positions it plans to add over the next two years.

In most cases, the automakers are looking for engineers with hard-to-find skill sets and sometimes want years of experience. That has the companies scouring the country for talent and universities working rapidly to retool their courses to meet the demand.

“We need more students going into engineering and into the automotive industry,” said Leo Hanifin, dean of the University of Detroit Mercy’s college of engineering.

Despite a surge in hiring, engineers who lost their jobs over recent years may find it difficult to get jobs without additional training in electric vehicles.

A three-credit retraining course in advanced propulsion technology offered by Michigan Technological University fills every semester, said Jennifer Donovan, spokeswoman for the university. The course is only open to out-of-work automotive engineers with degrees.

It’s also difficult to find college programs that provide electric-vehicle engineering courses, said Kevin Snyder, 40, who works at Chrysler as vehicle testing engineer.

Ten years ago, when Ann Marie Sastry, an engineering professor at the University of Michigan, started teaching courses in advanced batteries, fewer than 20 would sign up. Several years later, it was drawing more than 100 per class.

Still, Sastry said universities must strike a balance between curricula that train students for the future without getting ahead of the industry.

Send questions/comments to the editors.