NEW YORK — Doris Kearns Goodwin has read a lot of upbeat material about American presidents, but some of the entries on the White House website were so sunny that they reminded her of the happy talk at Boston Red Sox games.

“When we go to the ballpark, they’ll put on the scoreboard the statistics of the players who are coming to bat and they’ll always find something good to say,” says the Pulitzer Prize-winning historian. “Maybe the guy has a .150 batting average, but they’ll say, ‘In the last six games, he hit .367.'”

The White House site, offers one-page summaries of all 44 presidents, granting equal time to sluggers and bench-warmers. Much of the material is taken directly from a companion book by the White House Historical Association first released in 1964 and last reissued in 2009. “The Presidents of the United States of America” is a glossy, illustrated paperback that includes a foreword by President Barack Obama, who writes: “I hope it not only teaches you about America’s past, but also ignites a passion to build America’s future.”

But the White House biographies offer an unusual history lesson. Some are examples of blatant boosterism and outdated scholarship. Others are oddly selective or politically incorrect.

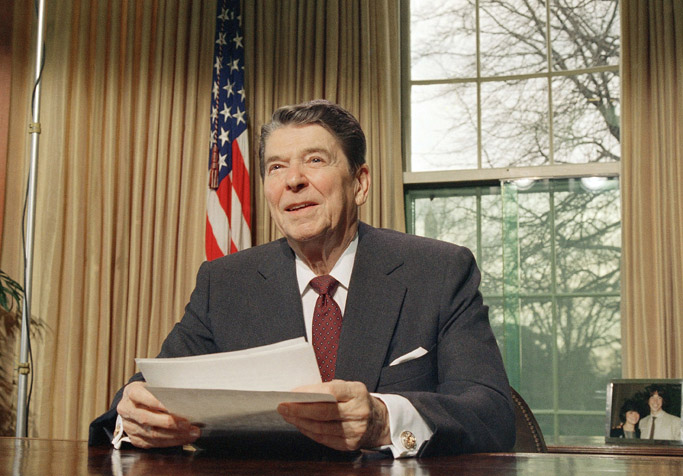

George W. Bush’s entry, for example, makes no reference to Hurricane Katrina or the economic collapse of 2008, but does find room for the names of his dogs. Ronald Reagan’s biography does not mention the Iran-Contra scandal, which made headlines during his second term. Gerald Ford’s 1974 pardon of Richard Nixon is noted in a few words, with nothing about the fierce criticism it received. Vietnam is included on Lyndon Johnson’s page (and spelled “Viet Nam”), but not his fateful decision to send ground troops.

Thomas Jefferson is introduced as a “powerful advocate of liberty” who “inherited some 5,000 acres of land,” but is not identified as an owner of slaves. Andrew Jackson’s page says virtually nothing about his advocacy of slavery or harsh treatment of American Indians. The life of William Henry Harrison, a military commander who became the ninth president, is narrated as a valiant crusade against Indians.

The White House declined to comment on the site, but spokesman Josh Earnest said the administration would consult with the historical association about updating it.

The biographies were commissioned during the Kennedy administration and were meant to complement the paintings of presidents that hung in the White House. According to historian and White House aide Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr., Kennedy “took a keen personal interest in the project” and would often check on the book’s progress. (On the White House site, the Kennedy administration is credited for raising “new hope for both the equal rights of Americans and the peace of the world.”)

“He saw the book not just as a portrait gallery, but as a distillation of the public history of the American democracy,” Schlesinger, who died in 2007, wrote in the introduction to the 1964 edition.

The White House Historical Association, an independent nonprofit established 50 years ago by then first lady Jacqueline Kennedy, said in a statement that “The purpose of the biographies … was to provide a brief, popular historical sketch to accompany the images of the official White House portraits and meant to enhance the public’s enjoyment of their White House tour.”

Historian Michael Beschloss, a member of the historical association and an editor of the 2009 companion book, would not comment directly on the biographies. He did say that one of the goals of the country’s revolutionary leaders was to bring a more democratic spirit to scholarship.

“The Founders felt that one of the most important things that differentiated us from the European regimes they wanted to get away from was that Americans would be and should be as relentlessly self-critical as possible and learn from both the successes and shortcomings of earlier generations of leaders and citizens,” Beschloss says.

The essays from George Washington through Kennedy that appear online were written by Frank Freidel, a Harvard University scholar and biographer of Franklin Delano Roosevelt who died in 1993. Paul Finkelman, author of a recent and disapproving biography of Millard Fillmore, thinks the early entries date back to the “consensus” theory of American history, when slavery was minimized and the most impassioned supporters of Reconstruction — Radical Republicans — were regarded as extremists.

The White House portraits of Fillmore and other presidents sympathetic to the South are softened and Lincoln’s assassination is regretted because it makes the alleged excesses of Reconstruction possible. “For with Lincoln’s death, the possibility of peace with magnanimity died,” the entry concludes.

“That’s a moronic statement,” says historian Eric Foner, author of “Reconstruction,” the acclaimed 1988 release that helped change thinking on the post-Civil War era, and winner this year of the Bancroft Prize and the Lincoln Prize for “The Fiery Trial,” a Lincoln biography.

“One would have to think about the purpose of the White House biographies. If the purpose is simply to instill admiration for all American presidents, it’s working. If the purpose is to give citizens a realistic sense of the presidents, it’s not working.”

Some of the most poorly regarded presidents receive the gentlest treatment. Herbert Hoover was simply a “scapegoat” for the Great Depression who became “a powerful critic of the New Deal, warning against tendencies toward statism.” Andrew Johnson, Lincoln’s immediate successor, is described as an “honest and honorable man” outsmarted by “Radical Republicans in Congress, brilliantly led and ruthless in their tactics.”

A new book about Johnson, by Pulitzer Prize winner Annette Gordon-Reed, shows him very differently. Gordon-Reed, winner of the Pulitzer for “The Hemingses of Monticello,” writes that Johnson was not a victim of the times, but a stubborn participant, an advocate of restoring white domination in the South. He was committed, in his own words, to “a country for white men” and a “government for white men.”

Gordon-Reed called the Johnson biography on the website “a pretty positive assessment” that “follows the line that the Radical Republicans were the villains.” She also noted that the entry twice referred to blacks as Negroes.

“What’s with the use of ‘Negroes’ in a modern document?” she said. “Very strange.”

Some essays leave out seemingly essential information. Harry Truman’s does not mention his upset victory over Thomas E. Dewey in 1948, while George W. Bush’s offers no detail about the prolonged election of 2000. Ford’s includes some of his comments upon succeeding Nixon, but leaves out the most famous words: “Our long national nightmare is over.”

Other entries are oddly personal. James Buchanan, Lincoln’s immediate predecessor, presided over the rapid dissolution of the country. But his page begins with a seemingly more meaningful detail: He was the nation’s only bachelor-president. James Madison’s story opens even more intimately. He was “a small, wizened man,” who appeared “old and worn,” and might have pleased no one but for the charms of his “buxom” wife Dolley.

Recent biographies, their authorship undetermined, suggest a competition for who made the country most wonderful. Reagan’s notes that “the Nation was enjoying its longest recorded period of peacetime prosperity without recession or depression” at the end of his second term, in 1989. Clinton’s page boasts that “the U.S. enjoyed more peace and economic well being than at any time in its history.” President George W. Bush’s tax cuts “helped set off an unprecedented 52 straight months of job creation.”

Not all presidents are judged successes. Ulysses Grant “provided neither vigor nor reform,” his biography reads. “Looking to Congress for direction, he seemed bewildered.” Franklin Pierce had hoped to ease tensions between North and South, but his policies, “far from preserving calm, hastened the disruption of the Union.” The wrongdoings which would define Warren G. Harding’s administration are noted, as is the Watergate scandal which brought down Nixon, and Clinton’s affair with White House intern Monica Lewinsky.

The companion book is much more balanced on the past few presidents, with the newer essays written by Beschloss. Katrina is noted in the Bush entry and Iran-Contra for Reagan. Subtle changes are made elsewhere. “Negroes,” in Andrew Johnson’s entry, becomes African-Americans. “Buxom” is gone from Madison’s biography.

The Obama page, written just after he took office, is highly favorable. He is presented as a gifted and civic-minded politician facing “the gravest economic crisis since the Great Depression.” The entry states that the country’s founders would not have expected an African-American president and cites Obama’s election as proof “the American system was still open to fresh talent.”

Online, Obama’s biography is equally positive, but quite brief — just six paragraphs — with no details about the historic 2008 campaign. It ends with his inauguration.

Send questions/comments to the editors.