PEARISBURG, Va. – Nearly 12 years ago, in the aftermath of the shootings at Columbine High School, officials quietly posted the Ten Commandments on the walls of the Giles County public schools. It was a natural reaction, said residents of this rural county peppered with churches, to such an alarming moral breakdown.

There the commandments stayed, within nondescript frames that also featured the first page of the U.S. Constitution, stirring little controversy until December. That’s when an anonymous complaint prompted the superintendent to order the removal of the displays. The decision sparked such passionate community backlash that the county school board voted to post them again in January.

Now the fight appears headed to the courts as residents of Giles County, along Virginia’s rugged, southwestern spine, fight what they call mounting pressure from Washington and Richmond to secularize their public institutions. The district also runs a so-called “Bible Bus” so that students can get privately organized Christian instruction off site during the middle of the school day.

“The commandments have been a compass for our lives,” said Jared Rader, principal of the county’s Macy McClaugherty Elementary School. “It’s something that the county feels strongly about, something we think our children should learn from.”

ACLU PLANS TO SUE

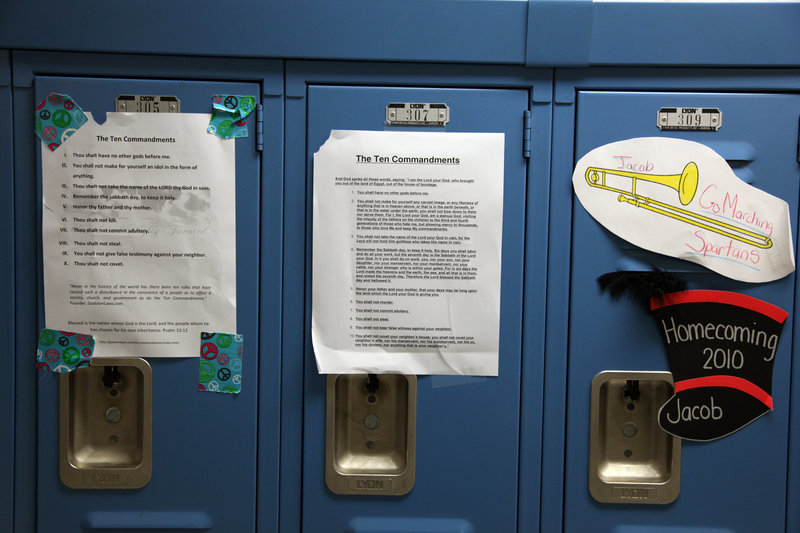

The commandments are featured on 8 1/2- by 11-inch pieces of paper in six schools, generally hung on white cinderblock near main entrances and hallways.

School officials say the displays should be legal because the commandments are a historical document, included as part of a monument to the principles — some of them religious — on which the country was founded.

The American Civil Liberties Union and the Wisconsin-based Freedom From Religion Foundation disagree. They plan to file a lawsuit on behalf of two plaintiffs, who have asked the court to withhold their names for fear of retribution.

“The school board is ignoring a core principle our country was founded on. Apparently they’ve never heard of the First Amendment or the Bill of Rights,” said Annie Laurie Gaylor, co-president of the Freedom From Religion Foundation, which describes itself as a national organization of atheists and agnostics. “And they’re using our schoolchildren as pawns.”

The displays were the idea of a Giles County pastor, and they have generated objections on at least one other occasion. In 2004, Sarah McNair, Giles High School senior, sent letters to county politicians, calling the display of the commandments an infringement on her rights and a “serious issue that cannot be ignored.”

Both Virginia’s secretary of education and the superintendent of public instruction dismissed her concerns, said McNair, now 23, who moved from Manassas, Va., to Giles County.

But when the issue flared again, in December, school officials consulted with legal counsel and decided to remove them. When students learned that the commandments had been removed, they distributed hundreds of photocopies of the edict, pasting them on lockers around the school. Weeks later, the halls were still papered with makeshift scrolls, next to photos of football players and fliers advertising sketch comedy routines.

“This whole thing just makes me feel small,” said Kearsley Dillon, 16, a sophomore who helped distribute the commandments. “I have my faith, and that’s the most important thing to me. But this is really discouraging. What can a 16-year-old do?”

UNANIMOUS OFFICIAL APPROVAL

The turning point was a raucous school board meeting attended by more than 100 Giles County residents. Hanging the commandments is “a right” and “a blessing” and “a moral obligation,” residents said in the public forum.

By the end of the meeting, the school board had voted unanimously to restore the Ten Commandments. And the Board of Supervisors soon after decided to support the decision, agreeing to help fund the district’s legal defense.

“We would rather fight the ACLU or whoever would come up than have one anonymous coward who would not even sign the letter come in and tell us how to run our schools,” said Eric Gentry, chairman of the county’s Board of Supervisors.

Public displays featuring the Ten Commandments have caused legal clashes for decades.

The Supreme Court ruled in 1980 that a Kentucky policy requiring the commandments on the walls of public school classrooms violated the First Amendment. But in 2005, the court upheld the inclusion of the commandments as part of a monument that included 16 other historical documents on the Texas State Capitol grounds.

Scholars say that the 1980 case, Stone v. Graham, will probably preclude the school board from legally displaying the commandments on school grounds.

“The school board is making a bet that the Supreme Court will overrule that decision,” said Douglas Laycock, a professor of constitutional law at the University of Virginia School of Law. “For a little school board down in the mountains, it’s an expensive endeavor.”

Although court decisions have underscored the line between church and state, many residents — who are quick to call Giles a “Christian county” — have expressed a desire to fight back against federal and state intrusions.

Some of the county’s government buildings feature posters reading “In God We Trust” near their entrances. After the Supreme Court ruled that prayer in school was unconstitutional, the district introduced its weekly Bible Bus, which facilitates religious classes for most of the county’s elementary school students. That initiative is legal, according to local officials, because it’s voluntary, and the bus is privately owned and operated.

Elsewhere in the nation, schools are trying to keep religion in public schools — including prayers at high school football games and in classrooms, and nativity scenes on school property. The Freedom From Religion Foundation every year receives about 300 formal complaints, many involving school districts, according to Gaylor. Yet she called the Giles County case “one of the most egregious we’ve seen.”

LOCALS SEE SOLID SUPPORT FOR DISPLAY

In Giles, residents say the Ten Commandments display enjoys nearly universal support among those who grew up in the county. They say only outsiders, such as legal organizations in Richmond and Wisconsin, would question such a core aspect of the culture.

Some consider Jonathan Jochem to be such an outsider. An ACLU member, he moved to Giles County from Chicago 11 years ago and quickly fell in love with the open spaces and the generous people. “They’re good Christians in the best sense of the word,” he said. “But their knowledge of the Constitution is distorted.”

Jochem was shocked when he first heard about the county’s Bible Bus, and bothered by the school board’s refusal to remove the commandments from public schools. Like several other community members, he supports the ACLU’s lawsuit.

But with the current controversy spurred by an anonymous complaint, and a lawsuit expected to be introduced with two anonymous plaintiffs, Giles County residents say they have little reason to believe that there is much of a local fracture.

The debate, said Shahn Wilburn, the pastor who first suggested displaying the Ten Commandments after Columbine, is “Giles County versus Washington. David versus Goliath.”

“I know that story,” he added. “And I know who won.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.