ATHENS – John and Linda Chapman started feeding deer 20 years ago after a bad spring when dead deer surrounded their rural home.

Most winters they see 12 to 20 deer from their living room window at the feeding stations set apart in the woods.

They spend up to $20 a week for a bag of farm feed, the kind used for cattle.

Two winters ago, they saw only two to three deer and worried. Now these hunters boast of taking bucks with thick antlers during deer season, whitetails that benefit from their winter buffet.

They say the feeding helps the local herd and the bucks they tag are proof.

“When you see them jump and carry on like dogs, with a full belly and feeling good, you know you’ve really helped something. If you have strong, healthy deer, you know,” Linda Chapman said.

Next week in Augusta, Sen. David Trahan, R-Waldoboro, is going to unveil a massive whitetail deer plan to help bolster the failing deer herd in western, northern and eastern Maine.

Trahan promises more will be done in the Legislature this session concerning deer yards, supplemental feeding and the overall protection of whitetails.

Part of that plan involves teaching and helping sporting clubs across the state to feed deer, Trahan said.

This legislative nod to the deer feeding practice will delight the Chapmans in Athens, but may challenge biologists.

In Maine, feeding deer can hurt whitetails more than help, and biologists view the custom — even tradition — with frustration.

“It’s a very emotional debate,” said state deer biologist Lee Kantar in Bangor. “People do it and swear it’s positive for the deer and it doesn’t matter what the science and the department say. That is a battle we are not going to win.”

The Maine Department of Inland Fisheries and Wildlife recommends feeding through herbaceous seeding along logging roads.

The department discourages winter feeding with handouts, because, if done wrong, the artificial food source can hurt deer, even starve a herd, biologists say.

Deer need protein, which they get from browse, particularly maple trees. Grain kernels empty of protein will leave a deer malnourished.

In addition, deer prefer room to eat. When crowded together, deer will fight, even with their offspring.

Finally, deer traveling across busy roads to get to feed invariably result in road kill.

All of these problems make deer feeding a practice that requires consideration and money, not just corn thrown in the backyard.

And the kind act can spell peril if it stops.

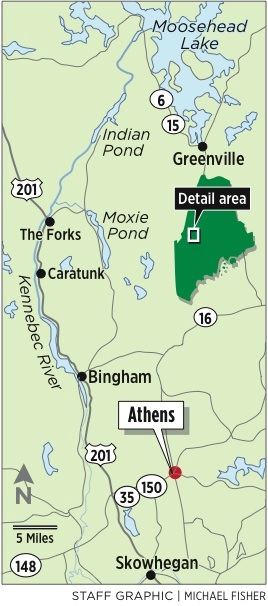

“If they are fed eight to 12 to 15 years and all of a sudden that stops, there is a fairly significant chance they won’t survive, even though they have an innate ability to seek out the best cover,” said state wildlife biologist Doug Kane in Greenville.

But Kane and Kantar concede, the practice — and problem — of feeding deer is here to stay.

“It’s difficult for me to find a large concentration of deer wintering that are not influenced by artificial feeding,” Kane said. “When we fly over our deer herd, they concentrate almost exclusively where there is artificial feeding.”

Given the widespread practice, Trahan said the time has come to teach Mainers how to feed deer.

“IFW should play an important role in teaching how to do it properly. They are trying to discourage deer feeding in the winter. I’m at the point, I want to teach people how to do it responsibly,” Trahan said.

The Chapmans do a lot of what the state recommends: feeding a grain mixture full of protein; feeding far from a road; feeding in small stations that are set apart and near a water source.

They feed the deer near their home with a mixture they buy at a local feed store.

The grain bag is full of molasses, apples and flaked corn.

Once a day, John Chapman dumps a 5-gallon bucket of feed on 10 to 12 raised wooden pallets in his yard, spreading out the feed so the deer do not congregate.

He tries to keep the feeding area clean and the food dry.

“It helps them get through the winter. They are not so starving. And this year we are seeing a lot more,” Chapman said. “During the bad winter, we found seven dead deer. When you see the deer playing, you see you’re putting back into nature.”

Still, Kantar warns that if other people begin feeding deer, and do it wrong or stop, the deer will be worse off than if they were left to their forage.

“So this ‘doing it right’ deal is an important point,” Kantar said. “Somebody like John Chapman may be doing it right. But just because John is doing it right, doesn’t mean the next person is. And it’s a cost to people. And right now, everyone is strapped economically.”

Staff Writer Deirdre Fleming can be contacted at 791-6452 or at:

dfleming@pressherald.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.