In 1984, John Lane stuffed 4-year-old Angela Palmer into an oven at an Auburn apartment and turned on the dials. Cynthia Palmer, Angela’s mother, was in the next room with her other daughter, Sarrah, at the time.

Lane said Angela had turned into a devil, and he had to get rid of her. The case received worldwide attention.

Elliott Epstein is a lawyer who lives in Auburn, about a mile from where Angela Palmer died. Epstein had a minor role in the trial in which Lane was convicted of murder and sentenced to life in prison, and Palmer was acquitted of any crime.

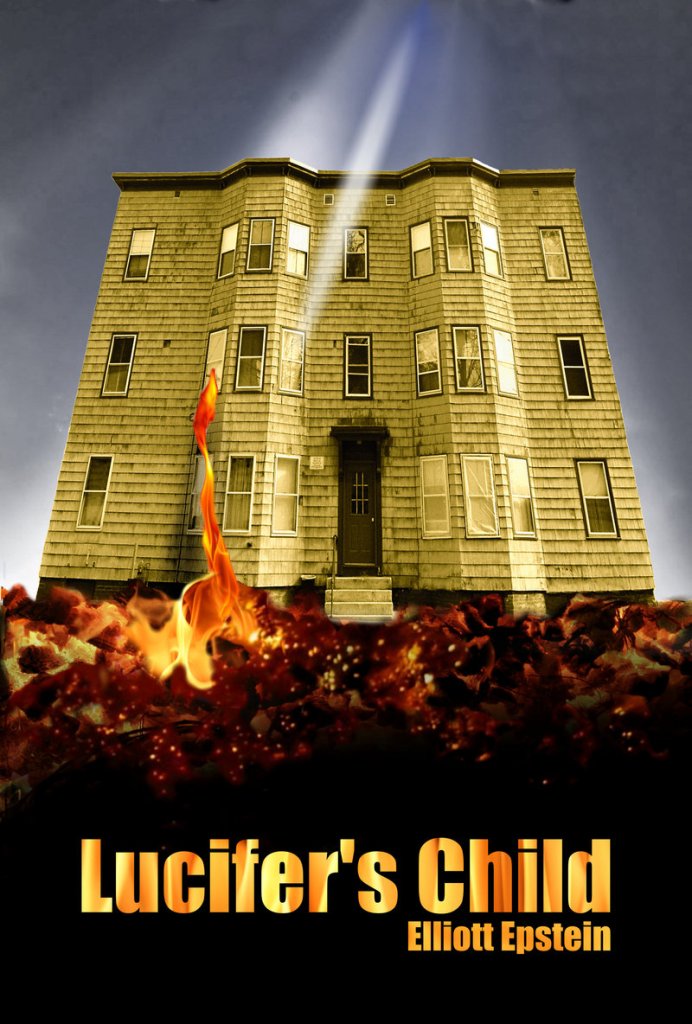

Epstein has written a book that tells about that case and looks at the causes. While “Lucifer’s Child,” published by Author House, tells the story of the crime and the trial, it also looks at the early lives of Lane and Cynthia Palmer, the abuse they suffered, and how Lane could come to commit such an act and Palmer would be powerless to stop it.

Epstein practices law in Portland and was a reporter for The Portland Press Herald while attending law school.

Q: At first glance, this is a book about a horrific crime, but it’s really a book about child abuse, isn’t it?

A: That is correct. I wasn’t intending to be the next Stephen King. I wasn’t writing the book about the murder of a little girl to be a horror story, but instead to highlight the problem of child abuse.

Q: What changes should be made to prevent something like this from happening again?

A: A lot of things have already changed over the past 26 years since this happened. Angela’s murder was a catalyst for some of them. For instance, more victim advocates were hired in the days immediately after this case, more child protection workers were hired. Police departments instated officers who were trained to investigate child-abuse cases, particularly sex-abuse cases.

So in some sense things have changed for the better, but there still is a lot that needs to be done. For instance, I think that one of the things highlighted by this book is that when children are abused — particularly sexually abused by their father, stepfather (or) mother’s boyfriend — that very often the mother will be passive or turn a blind eye, and that tends to be linked to the abused-woman syndrome. These women have been so beat down emotionally and physically that they don’t have the psychological ability to do something to protect their own children.

One of the things that has to be done is to make a better effort to reach out to abused women. This isn’t something that necessarily has to be done by the government. It can be done by private organizations. These women need to be reached, given treatment, educated and given a support system so they are able to protect their own children.

Q: My family members and people at the office looked at the cover and title of your book, found out what it was about, and reacted with disgust. You can tell they are not really interested in reading this. Is it selling OK, do you expect it to sell OK, and what is the audience?

A: The audience in part are the people living in the community where it happened. The memory about this incident runs very deep. Secondly, I think it is a book for professionals in the field, not strictly as an academic-type book — there are no footnotes. It is a kind of case study for people in the field, who work for abused-women’s shelters, social workers and psychologists. I also would like to see it offered as an educational tool for abused women undergoing treatment so they can see what the probable result is of failure to change their patterns.

A lot of people told me they were reluctant to read the book because of the horrific nature of the crime, but having read it, understand the reason that I wrote it.

I was contacted by some people about a year ago when a story first appeared in the Lewiston paper about the fact I was writing a book. A woman named Jan Whitt attended the trial and wrote a story in the Maine Times in February 1996, which talked about the impact the case had on a number of reporters who covered it. She quoted Roberta Scruggs, who was working for the Sun-Journal at the time, who said the people of Maine “were stunned. It was beyond anger. It wasn’t a conspiracy of silence, but no one ever talked about it.” Scruggs also said, “There is no end to it.”

And that is true. Few people talked about it. They buried it inside of themselves. But I’ve slowly been getting contacts from people who were involved one way or another, but now understand that it needed to be resurrected.

Q: Did you try to get in touch with Cynthia Palmer or Sarrah (Palmer’s surviving daughter) to find out how they turned out? You did write that John Lane was still in prison.

A: Well, the book took me through the end of the trial, and that is where I stopped. I certainly was curious about what happened with the people, and some of them have slowly been getting in contact with me, including John Lane, who has written to me. It is possible that I may do some kind of newspaper or magazine article on what has happened with the major personalities in the trial. I did learn that Cynthia Palmer died in 2005.

Q: What was your role in the trial?

A: It was very minor. I was a representative of a large mental health agency, Tri County Mental Health, and several of their therapists were subpoenaed to testify My entire part took about a half an hour, and I ended up staying there for at least a week of the trial.

Q: Is there anything else you would like to say?

A: One of the things that occurred to me as I was writing the book is that what made this case unique was the horrific nature of the murder. It is hard to get more brutal than shutting a child in the oven and then turning on the dials. Children are injured and killed all the time in a variety of different ways. Sometimes they are shaken to death, sometimes they are drowned and sometimes they are beaten to death.

But what this case did particularly well was to explain why people act the way they do. It was one of the basest examples of the abused women’s syndrome. People were angry at Lane — he is the one who actually killed Angela — but they are mystified at Palmer’s failure to protect her daughter, her inability to react to what was going on in the very next room. And that is what this book explains in detail.

I think also it is a testament to the individuals who investigated and tried the case. Despite the fact that it received all sorts of media attention all over the world it was all handled with dignity and decorum, unlike, say, the O.J. Simpson case.

Tom Atwell can be contacted at 791-6362 or at:

tatwell@pressherald.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.