PORTLAND — Maine’s two semiconductor makers have appealed to the administration of Gov. Paul LePage to ease what they call overly burdensome regulations covering the treatment of solvents used in manufacturing.

National Semiconductor and Fairchild Semiconductor, which both have operations in South Portland, have asked the administration to align the regulations of Maine’s Department of Environmental Protection more closely with those of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, which they say are more practical.

At issue is how Maine regulates the disposal of some solvents, including isopropyl alcohol, used to make semiconductors. The solvents, which can be flammable, corrosive and toxic, are classified by the DEP as “hazardous waste.”

Federal law, however, doesn’t go that far. The EPA, and some states, exclude some of the solvents from the “hazardous waste” designation.

“The EPA allows you to do certain things that Maine’s DEP does not,” said Anne Gauthier, spokesperson for National Semiconductor. “Even (California) has accepted the federal exemption.”

“Maine’s DEP definition for a hazardous waste is much stricter than the federal EPA standards,” said Fairchild spokesperson Patti Olson in a statement. Changing to federal standards, she said, would let them resell or recycle the solvents.

Olson said Fairchild’s disposal costs can top $50,000 per year. The company could earn $200,000 by selling a year’s worth of the chemicals, she said.

Gauthier said National submitted paperwork about the issue to the administration of then-Gov.-elect LePage, which had asked companies for input as part of LePage’s regulatory reform efforts.

And Fairchild raised the issue at a recent Red Tape workshop held in Portland.

In a statement, Dan Demeritt, LePage’s communications director, called the solvent issue an “excellent example of the type of opportunities Governor LePage was looking for when he launched his red tape audits.”

Though the regulatory reform package is still under development, he said the administration is “aware of the costs and the opportunities that may exist to recycle and reuse some items safely and at a significant savings.”

Olson said the administration has listened to their concerns and suggested follow-up meetings.

Maine law requires companies to pay 3 cents per pound for hazardous waste. But the companies say they pay related hazardous-waste costs, such as tank cleaning, shipping and handling expenses.

Les Gardner, an environmental engineer at National, said his company spent roughly $62,000 per year dealing with hazardous materials in 2009.

“It is a tax, and it doesn’t help Maine industry,” he said.

Gauthier said classifying the solvents as hazardous waste dissuades efficient use of materials. After National pays all the fees and completes its reporting, there is little incentive to have the materials recycled.

“You are already paying for it. Why would you put more effort into it?” she said.

Gauthier said the industry has a record of being “conservation-minded.” National, she said, continually seeks ways to reuse materials. For instance, she said the plant reuses water to make steam, which humidifies the factory floor.

“Our mentality is to think about how we can use something two or three times to keep costs at a minimum,” she said. “This flies in the face of our own thinking.”

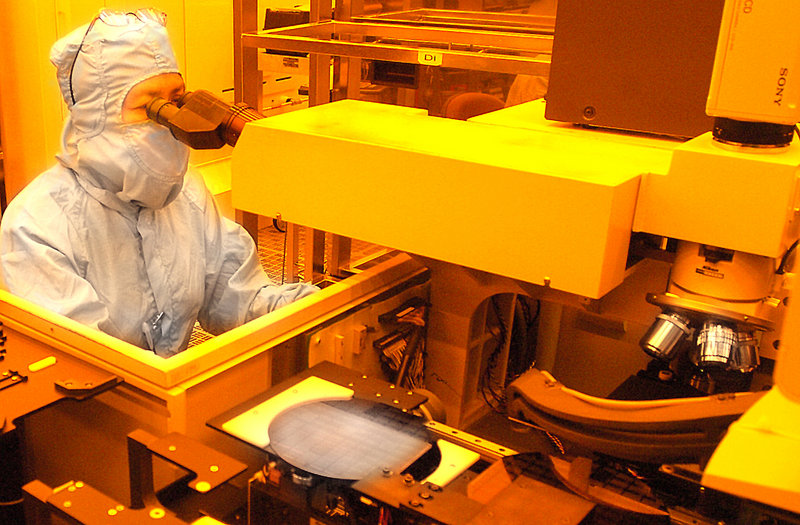

Semiconductor makers are tight-lipped about the solvents, which help strip away the chemicals manufacturers use to etch lines in the silicon chips. Gauthier said the chemicals are a critical and proprietary part of manufacturing.

But hazardous-waste reports from the DEP give details.

According to the DEP, in 2009 Fairchild paid roughly $16,000 in state fees on some 600,000 pounds of hazardous waste.

National’s fees totaled some $34,000 on some 1.1 million pounds of waste.

Each company also paid the maximum $1,000 in fees for the state’s toxic-use-reduction program.

Among the chemicals in the reports are isopropyl alcohol, acetone, fluoride solution and glycol ether mix.

DEP Division Director Scott Whittier said the regulations ensure that waste is properly contained and disposed of. They also ensure it is carried on special trucks to avoid contamination with other products, like food.

And Whittier said the materials are, indeed, hazardous — toxic, reactive, ignitable and corrosive.

“Those qualities exist in the unusable materials,” Whittier said. “The hazardous characteristic of the waste doesn’t change whether it is going for recycling or not.”

Still, he understands why manufacturers want changes.

The companies have specific specifications for chemicals, he said, and slight changes make them unusable for chip making but still valuable. Also, materials designated hazardous waste are hard to resell because buyers avoid them, he said.

And though Whittier said “some amount of regulation is needed,” he added that his agency is willing to talk to chip makers about changes if they have a proposal.

Staff Writer Jonathan Hemmerdinger can be reached at 791-6316 or at:

jhemmerdinger@mainetoday.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.