AUGUSTA – There were early signs within the John Richardson for Governor campaign that it might not qualify for public funds, a review of e-mails released by the state shows.

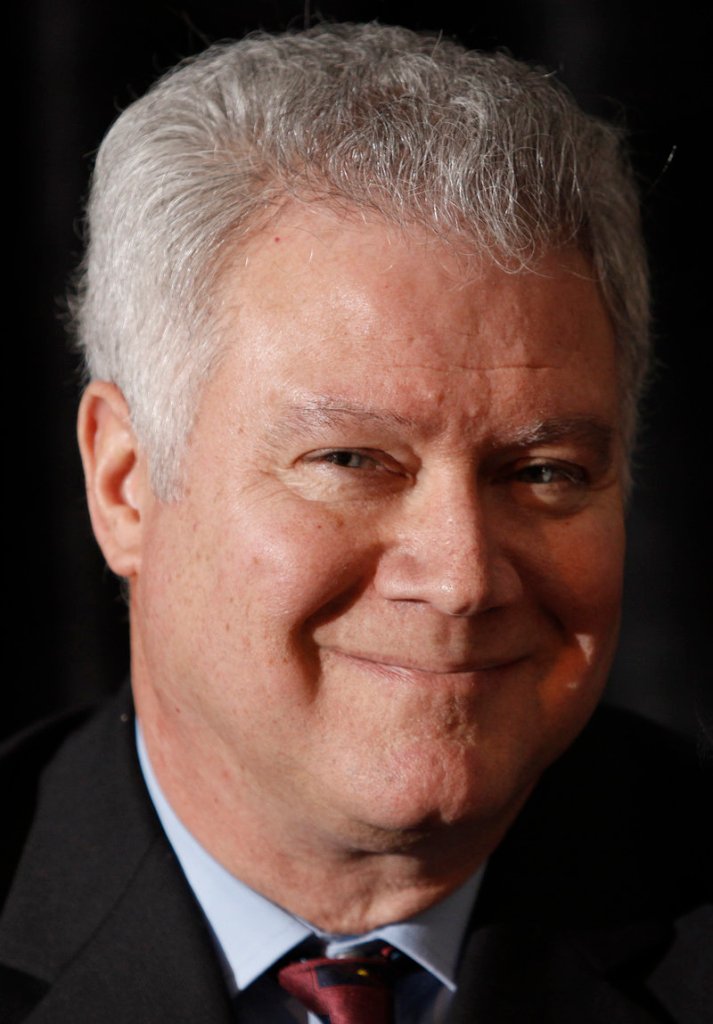

Richardson, a Democrat and former House speaker from Brunswick, was one of four gubernatorial candidates who sought to participate in the state’s Clean Elections system prior to the June primary. If successful, Richardson would have received $600,000 in taxpayer funds for the primary, or a total of $1.8 million through the general election.

Ultimately, he was denied the funds, and charges have been levied against four campaign volunteers who allegedly falsified documents while collecting $5 contributions required to qualify for the money.

Dozens of e-mails released by the Maine Commission on Governmental Ethics and Election Practices in response to a Freedom of Access request by the Kennebec Journal help fill gaps about how the process unfolded for the campaign.

The state has yet to release additional e-mails that related directly to the investigations into the Richardson campaign by either the ethics commission or the Maine Attorney General’s Office.

Flags were raised about the Richardson campaign as far back as February — two months before the ethics commission rejected its bid for funding.

In an e-mail to answer various questions from the campaign about how to collect seed money — one of two requirements to receive full public financing for a gubernatorial campaign — an ethics panel staffer sent a brief message to the commission’s executive director, Jonathan Wayne:

“FYI. It makes me wonder if they will be able to qualify. Only 42 days to go.”

Also in February, Wayne notified the campaign there was reason to believe one of its volunteers was violating Maine law by telling potential donors he would cover a $5 contribution if they simply signed the required paperwork.

Wayne refused to tell the campaign which volunteer was suspected. Later, Richardson said not knowing that information left the campaign at risk of submitting “tainted forms,” which is exactly what happened.

This week, Richardson said he is uncomfortable talking about the case while charges are pending against his former volunteers. Richardson has not been accused of any wrongdoing.

Despite his staffer’s e-mail, Wayne said this week he didn’t feel Richardson lagged far behind the other campaigns in its application for funds.

“The commission staff didn’t have serious concerns Richardson was running late as early as February,” he said. “We encouraged all candidates to start early and submit stuff in batches for us to review.”

While the campaign did collect the $40,000 in seed money required by state campaign finance law ahead of the deadline, it was a mad dash to the finish to meet the other, tougher standard: 3,250 qualifying contributions of $5 each.

“Richardson turned in a larger proportion of contributions on April 1 (than the other campaigns),” Wayne said. “There was a higher level of disorganization with those.”

In the end, the commission not only determined the campaign did not meet that requirement, it also suspected four Richardson workers of cutting corners while collecting donations.

Earlier this month, the Attorney General’s Office filed charges against the volunteers, accusing them of falsifying certification forms for the $5 contributions. The individuals facing charges are Joseph Pickering, 54, of South Portland; Denise Altvater, 51, of Perry; Lori Levesque, 46, of Fort Kent; and William Moore, 46, of Brunswick.

On April 26, after he was denied the funds, Richardson dropped out of what was then a five-candidate Democratic primary.

In a statement to supporters, he talked about his deep disappointment at having to end his run for governor.

“Every one of our circulators was given specific instructions from me or campaign staff as to how to collect contributions,” he said. “And everyone was told — and expected — to follow the letter of the law at all times.”

Two other Democrats — Libby Mitchell and Patrick McGowan — used the system to pay for their campaigns. So did Republican Peter Mills of Cornville.

Richardson, a labor lawyer and former head of the state’s Department of Economic and Community Development, had often touted the importance of keeping corporate money out of Maine politics.

The Clean Election system is an attractive option, because once a candidate qualifies, it eliminates the need for fundraisers or dialing for dollars — a time-consuming and uncomfortable pursuit for many.

For perhaps these reasons, 76 percent of legislative candidates are using Clean Elections funding this year, and three of the gubernatorial candidates used it in the primary.

But it’s not easy to qualify for it.

In the race for governor, candidates who wish to use public funds must collect the $40,000 in seed money to prove they have viable support. That money can come only from individuals who are registered Maine voters and must be in increments of no more than $100. Then, candidates must collect the additional 3,250 contributions of $5 each.

All these donations must come from registered Maine voters. Checks and money orders collected by a campaign circulator must come with a “receipt and acknowledgment” form signed by the donor and circulator.

signing the form, the donor swears the $5 came from personal funds in support of the candidate, and that they did not receive anything of value in return for the contribution.

The circulator swears he or she collected the contribution personally and did not provide anything of value in return for the $5, according to the 102-page guide published by the ethics commission.

Candidates who have used the system say the qualification process requires a tight, coordinated effort with direct oversight, attention to detail and numerous calls to ethics commission staff.

E-mails released by the state last week show a trail of questions from the Richardson campaign, including a last-minute request on fixing “problems with qualifying contributions” after the April 1 deadline.

After a meeting with Juanita Phillips, deputy treasurer for the Richardson campaign, candidate registrar Sandy Thompson reported this to her colleagues on March 17:

“When I met with Juanita yesterday to review the Richardson campaign’s submittal of seed money documentation and batch 1 of qualifying contributions, she commented that ‘candidates’ for governor (John Richardson) do not understand the amount of work it takes to qualify for public funds. She thought that Peter Mills understood because he ran as an MCEA candidate in 2006 but that the others did not.”

That prompted a reply from a fellow staffer who wrote:

“Maybe we can collect some testimonials (warnings?) for the 2014 candidates. “

Thompson replied: “That’s a good idea.”

At 2:07 p.m. on March 31, the day before the deadline, Wayne e-mailed staffers and Assistant Attorney General Phyllis Gardiner with an update on the progress of the Richardson campaign.

The e-mail said the campaign planned to submit more than the required number of “contributions by the 5 p.m. deadline on April 1.”

Wayne also issued a four-page memo to the campaign that outlined what the campaign could and couldn’t do once the deadline had passed.

It would not be acceptable, for example, to submit documents past the deadline, he wrote, but in “limited circumstances,” documents could be amended.

The campaign met the deadline. That started the clock on a review by ethics staff to make sure all the documents and contributions were in order.

On April 5, an e-mail from Thompson to other staffers gives an update on “Batch 5” of the Richardson submission:

“281 Accepted, 31 pending (correctable) and 29 rejected. Rejected number includes some contributors who were entered in wrong address/town on the Excel list. I added these contributors to the correct town and accepted them.

“It’s another example of hasty work,” she wrote.

On April 8, Phillips wrote to the commission to clear confusion about multiple contributions from F. Lee Bailey — the noted criminal defense attorney who contributing seed money online through a software provider.

But instead of charging his card only once, a third-party payment processor withdrew $100 in January, February and March. The campaign caught the error and returned the funds.

A few days later, the e-mails suggest the campaign had concerns.

On April 13, Monica Castellanos, Richardson’s campaign manager, sent a note to Wayne with the subject line “checking in.”

“I just got off the phone with Juanita, who seems concerned after talking with you. Would you please give me a call as soon as possible? Thanks.”

A day later, Castellanos was working to clear up paperwork issues and asks for time with Wayne “to better understand the process.”

Castellanos, who is now working on the campaign for independent Eliot Cutler, declined comment for this story.

April 20, three weeks after the deadline, reporters were calling Wayne regularly to find out why no determination had been made on whether Richardson had qualified. He indicated that he planned to finish up the staff recommendation that day — April 20 — but that it likely would not be by 5 p.m.

On Thursday, April 22, at 6:11 p.m., Wayne sent the campaign the final version of his staff determination rejecting Richardson’s application.

The 13-page memo detailed staff concerns that Richardson campaign volunteers “engaged in unacceptable activities such as falsifying qualifying contributions and forging signatures on money orders.”

It also let Richardson know he could appeal the decision, with a hearing held within five days.

In his speech to supporters the following Monday, Richardson explained that he considered an appeal, but decided against it.

“An appeal to the ethics commission and the time involved to further investigate the questionable forms — even if we were to prevail — wouldn’t leave any time for us to address the real issues in this race,” he said.

“And that would not be a good use of public funds.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.