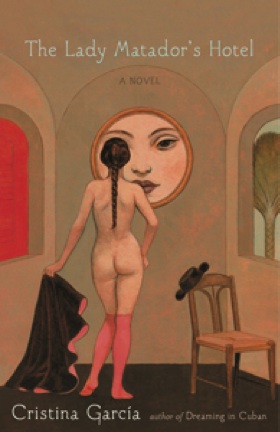

On the first page of Cristina Garcia’s new novel, the lady matador stands naked before a mirror, rolling on a pair of long pink stockings as part of her preparatory ritual for the bullfighting ring.

The ceremony has other steps, too: lighting candles for her mother, eating a single sliced pear — seeds and all — and, for extra luck, having silent sex with a stranger two days before a fight.

When she finally steps into the ring, she repeats three words in Spanish and Japanese.

Arrogance. Honor. Death.

“The Lady Matador’s Hotel” is filled with those elements, plus hefty doses of lust, violence and bad intent. It’s a ruthless romp through an anonymous Central American capital buffeted by the winds of political turmoil. Suki Palacios — she of the pink stockings and unusual appetites — has arrived with her all-male entourage to compete in the first Battle of the Lady Matadors.

Sweeping through the lobby to a news conference while dressed in yellow — “the color of accidents and ill omens, of bold overtures to gorings, and worse” — the Japanese-Mexican-American “matadora” inflames reporters with her casual contempt for them even as she inflates her own image as a dangerous breaker of rules and tempter of fates.

And her fate is entwined with those of others in the hotel: a waitress who used to be a guerrilla, a lawyer arranging controversial international adoptions, a suicidal Korean manufacturer and his pregnant mistress, a Latin American colonel, a Cuban poet.

Brought together for a week, the hotel guests’ lives intersect in unexpected and explosive ways that shake the foundations of their beliefs and identities.

Garcia, whose novels include “The Aguero Sisters,” “Dreaming in Cuban” and “Monkey Hunting,” writes with an artist’s eye that serves the story well: The poet watches a nurse waddle off, white pantyhose rubbing together, almost giving off sparks. The colonel strolls through the night, defying his enemies, under a moon that mocks him and trees with ominously bare limbs. The manufacturer hears the hollow sound of grapefruit snapping from a tree as he searches for butterflies, wishing he could return to childhood days. The ex-guerrilla smoothes her pink-and-white apron, serving a general his pork chops on a round tray, imagining how — if the edges of the tray were serrated — she could decapitate him with the flick of a wrist.

Elegant death is everywhere in this book — poetic, graceful, contemplated almost as an art form. And those who dispense it accept the task as something ordained from on high. The ex-guerrilla plans a final mission. The manufacturer takes careful steps toward his own demise. The “matadora” worships at the altar of the ring where she must fight or die.

As Suki faces a demonstration fight — her female supporters waving signs saying “A woman’s place is in the ring!” and “Make tamales, not war!” — Garcia muses: “Without the bull, the matador is nothing. There’s no drama, no spectacle, no poetry. Without the bull, there is no glory. No immortality. In giving the bull the chance to fight for his life, everyone is redeemed. This passion Suki has for the bulls, their majesty, is paradoxical, she knows; a passion that must kill to achieve its highest expression.”

Garcia has created a half-magical world in which blood runs close to the surface and flesh is transitory, opening the door to the big questions of existence: Who am I, and what is my purpose in life? The answers she offers — such as they are — come with a sly wit and strong visual style that explodes with color and life.

She — and Suki — salute bravery in all its forms, quiet, flamboyant or somewhere in between. Facing your fears, in the form of a thundering bull or a fluttering butterfly, is the greatest triumph, she writes.

And then there’s Suki’s take on such matters: “We fear what we love most,” she tells the reporters at the news conference, as they crowd around her with their white hot lights. “And we especially love what we fear.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.