MALAGA ISLAND – It was, in all likelihood, a record crowd. Never before in its documented history had anywhere near 90 people gathered at the same time on this craggy, wooded island at the mouth of the New Meadows River.

Yet here they stood Sunday afternoon — elected officials, archaeologists, journalists, human rights activists and, most notably, descendants of the mixed-race families who once called this 41-acre island home — all to hear two simple words.

“To the descendants of Benjamin Darling, let me just say that I’m sorry,” said Gov. John Baldacci as a late-summer breeze whispered through the spruce trees. “I’m sorry for what was done. It wasn’t right and we were raised better than that. We’re better people than that.”

Maybe you’ve heard the story of Malaga Island — and then again, maybe you haven’t.

It’s not pleasant.

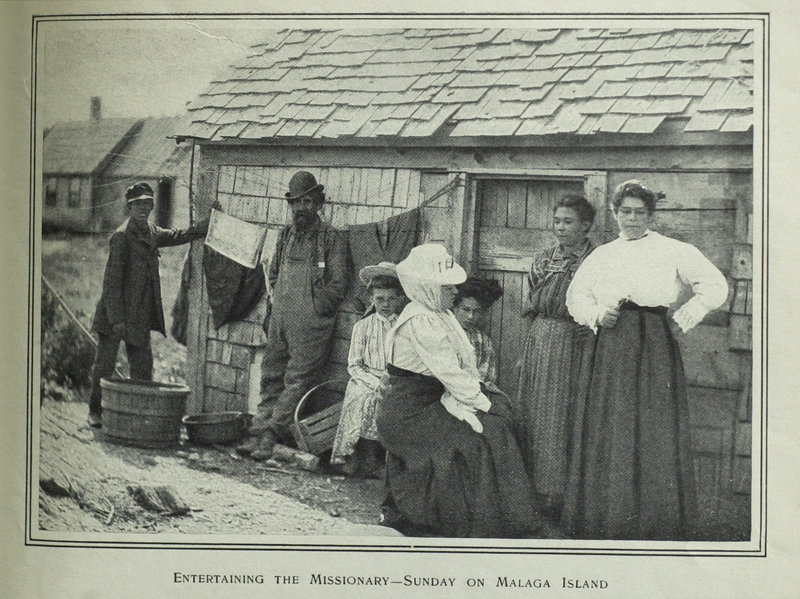

Just a few hundred yards from Phippsburg’s western shoreline, Malaga Island was home in the late 19th and early 20th centuries to anywhere from 25 to 40 people who lived in dirt-floor, ramshackle homes and eked out a living fishing the tides in the New Meadows River and doing whatever menial work they could find on the mainland.

Most traced their lineage to Benjamin Darling, a black man who had bought and settled on a nearby island in 1794. Some were black, others were white, still others were a mixture of the two.

Therein lay the problem, as reported in a 1902 edition of the Bath Independent under the headline: “Not fit for dogs. Life on Malaga.” An excerpt:

“Poverty, immorality and disease. Disgusting and pitiable. A population of 35, and 26 of them sick with measles. No food, no beds, no fuel and scant shelter all winter long. Ignorance, shiftlessness, filth and heathenism. A shameless disgrace that should be looked into at once. The town of Phippsburg disowns these creatures and they are made outcasts.”

Ten years later, amid widespread racial prejudice against the few blacks in Maine, a burgeoning eugenics movement that attributed poverty and low intelligence to interbreeding, and growing pressure to clean up the Maine coast and make way for well-heeled, out-of-state vacationers, Gov. Frederick Plaisted took action.

“I think the best plan would be to burn down the shacks with all of their filth,” he told a newspaper reporter. “Certainly the conditions there are not credible to our state. We ought not to have such things near our front door.”

On Plaisted’s order, everyone on the island was summarily evicted. Those houses that weren’t removed by their owners were burned. Islanders deemed to be “slow-witted” were carted off to what was then the Maine Home for the Feeble-Minded in Pownal, where they would remain for the rest of their lives. (According to press reports from the time, at least five died within months.)

And, in what was perhaps the most glaring indignity, state workers exhumed all 17 graves in Malaga’s tiny cemetery and unceremoniously reburied the remains among nine plots in the graveyard of the facility in Pownal. They remain there, at what is now Pineland Farms, to this day.

Over the decades, the story of Malaga has been kept alive by a small-but-persistent procession of historians, journalists, documentarians and descendants, many of whom still bear the telltale surnames of Darling, McKenney and Tripp.

But for years, it appeared there would be no formal accounting by the state, no acceptance of responsibility for this erstwhile sign of the times that would linger for almost a century as a stain on Maine history.

That changed this year.

On April 7, the final day of its session, the Legislature unanimously passed a resolution expressing its “profound regret” for the “tragic displacement of the Malaga islanders in 1912.”

Drafted by Rep. Herb Adams, D-Portland, the resolution went virtually unnoticed outside the State House — Adams said this week it was all he could do to get it voted on by the House and Senate in the hectic final hours of the session.

But it was a start.

“I feel like I’m on hallowed ground,” Marilyn (Darling) Voter of South Portland, the great-great-great-great-granddaughter of Benjamin Darling, said Sunday after setting foot on Malaga Island for the first time. “When I first stepped on it, I thought I was going to fall down and cry.”

Sunday’s gathering had two purposes.

The first was to formally dedicate a marker installed this summer by Maine Freedom Trails Inc., a nonprofit organization that commemorates the anti-slavery movement in Maine and, with this latest addition, its early African-American history.

The second, explained Rachel Talbot Ross, president of Maine Freedom Trails, was to persuade Maine’s current governor to come to the island and help close a near-century-old wound.

“We don’t know what he’s going to say,” an anxious Talbot Ross said as small fishing boats ferried the dozens of descendants and other visitors out to the island, which remains uninhabited and now belongs to the Maine Coast Heritage Trust. “We’re hoping for an apology, but we’ll just have to see what happens.”

The steady stream of visitors ranged from 80-year-old June McKenzie of Portland, a direct descendant of Malaga Island’s McKenney family, to 17-month-old Benjamin Darling of South Portland, the only Darling in nine generations to share the name of the family patriarch.

Truth be told, many of the three dozen or so descendants who made the trip had never met before Sunday. But that didn’t matter. All knew the story — and all knew that on this day, they needed to be there.

“What does this mean?” said Bill Fisher, June McKenzie’s 69-year-old nephew, who came all the way from Connecticut. “It’s like the pope apologizing for the Holocaust, that’s what it means.”

Finally, one of the last ferries nudged its bow up to the smooth granite rocks. Baldacci disembarked and walked slowly up a winding path to where archaeologists from the University of Southern Maine say the ramshackle homes once stood.

Along the way, the governor paused repeatedly to speak with descendant after descendant, shaking their hands and nodding sympathetically as they told him what it meant for him to be there.

“You don’t realize the impact until you see the tears streaming down people’s faces,” said a visibly moved Baldacci. “And then it really hits you — all the things that have gone on and all the things that have not been said and not done over such a long period of time.”

Then, with neither script nor formal proclamation, Baldacci did what most needed to be done. As he spoke, some in the crowd wiped their eyes, while others muffled their sobs.

“It’s reprehensible what happened to your families,” Baldacci said. “The spirit you bring today is a spirit that others can learn from. Because it isn’t about retribution and revenge and hate and violence. It’s about trying to find hope and opportunity.”

“Most important,” he said, “is to say that we’re sorry.”

There was no talk, nor will there be, of damages or settlements or reparations. Because the islanders never owned the land on which they lived, such claims would lack any legal basis.

And as deep as Malaga Island’s emotional currents still run after all these years, Baldacci later said the decision to make the apology was hardly a difficult one.

“Responsible officials did this to people who wouldn’t stand for it today,” he said. “So what is the only thing you can say? You can say you’re sorry.”

The Maine Freedom Trails marker, unveiled at the end of Sunday’s ceremony, will bear silent testimony in the years to come to the people who once lived here and the weight of an entire state government that came crashing down upon them.

But leave it to the historian Adams, flanked by three fellow legislators, to deliver Malaga Island’s benediction.

“Peace, at last to Malaga,” Adams bellowed in a voice loud enough to be heard over the ages. “May scientists explore its secrets. May students study its histories. May Mother Nature reclaim her own. And may the old ghosts find peace at last.”

Amen.

Columnist Bill Nemitz can be contacted at 791-6323 or at:

bnemitz@mainetoday.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.