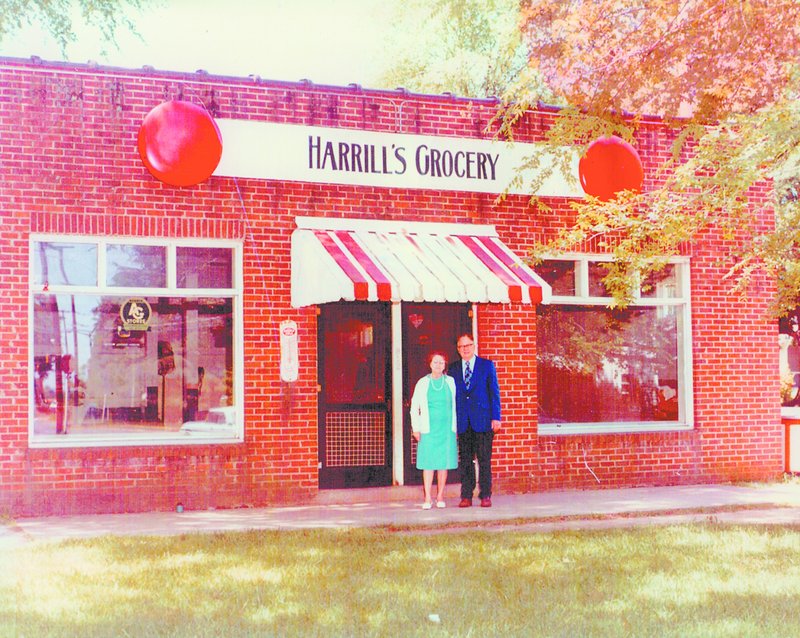

GAFFNEY, S.C. – Harrill’s Grocery, located just across East Frederick Street from the Harrill family home, was a big part of life in this small town.

It’s also where, in the 1950s, a woman who would become one of Maine’s most powerful politicians learned about hard work, interacting with the public and helping those who were struggling to make ends meet.

These skills shaped Elizabeth “Libby” Harrill from an early age, and helped her become who she is today: Senate President Libby Mitchell, the Democratic candidate for Maine governor.

Libby — nobody ever called her Elizabeth — stocked shelves and waited on customers. She traveled with her father as he made his rounds to supply other small stores with items like gum and aspirin. She watched her parents allow certain customers to put items on a charge slip, even though they knew some would never come back to pay.

“It was truly an honor system,” Mitchell said. “Nobody did without. If you were on hard times, my father always made sure you did not do without. You do not go hungry. I will not let you go hungry.”

Growing up in Gaffney, Libby Harill did all the usual things. She sorted peaches at the Sunny Slope peach shed in the summer. She cheered Gaffney High football on Friday night, went to the movies on Saturday and to church on Sunday.

Libby did some unusual things as well. She was student body president, Miss Homecoming, and was named “most popular” in the high school yearbook. Friends say she was a natural leader, even at a young age.

“Libby really had a very, very strong calmness about her,” said Mike Daniel, a former high school sweetheart and fellow 1958 Gaffney High School graduate. “She had really strong convictions.”

Libby Mitchell, born in 1940 to Charlie and Lula Mae, hasn’t lived in Gaffney since she graduated from high school in 1958. She hasn’t lived in South Carolina since working as a college admissions counselor at her alma mater, Furman University, in the mid-1960s.

In speeches in Maine, she has often said she “didn’t have the good fortune of being born in Maine but I came here just as quickly as I could.”

Yet her formative years in the 1950s — with sock hops, soda fountains, segregation and Sunday morning services at the First Baptist Church — framed the woman who hopes to be the first female governor in Maine’s history.

Her sister, Joyce Childers of Gaffney, has stayed close to the sibling she calls “Lib,” despite the distance between them, and the fact her little sister stole the show at Joyce’s seventh birthday party.

EARLY YEARS

Over a glass of sweet tea at her Gaffney home, Childers recalled the day — June 22, 1940 — her younger sister Elizabeth Anne was born.

“They kept saying you’re going to get a baby for your birthday,” she said. “They didn’t really think they would, so they bought me a doll.”

The doll was Princess Elizabeth.

“I was really upset because my mother had to leave my birthday party (to deliver the baby),” she said.

When her parents returned home, they asked what she wanted to name her little sister.

“I picked Elizabeth from that doll,” she said. “She was my birthday present.”

Her younger sister was born seven years to the day after she was, and the women to this day continue to celebrate their mutual birthday together whenever possible, as they did in Maine this past June.

A photo of the sisters taken that day now adorns Childers’ refrigerator in Gaffney.

With a seven-year age difference, though, the sisters didn’t become close friends until later in life. Childers remembers her baby sister tearing up her paper dolls and telling on Joyce when she misbehaved.

The girls’ father, Charlie, was a traveling salesman of household items to grocery stores. Later, he worked with his wife to open Harrill’s Grocery in the late 1940s.

Looking back, Mitchell said she loved working in the store, and her sister offered to do the housework so she could spend more time across the street with customers.

“The ultimate triumph was to get to operate the cash register myself,” she said.

Childers said their father, a member of the county election commission, strongly encouraged his girls to vote. She recalls going to the town square on election night to see the results being posted.

Politics was part of the family’s life. Their mother’s father, Jesse G. Wright, served as the elected Cherokee County sheriff in the 1920s and 1930s and served in the state House of Representatives in 1918 representing Gaffney.

According to the Journal of the General Assembly of South Carolina from 1918, Wright — whose occupation is listed as a farmer — chaired the Incorporations and Engrossed Bills committees and served on the Fish, Game and Forestry Committee.

Another relative, their mother’s cousin Julian Wright, was county sheriff from 1951 to 1970. (He’s noted in local history for apprehending the notorious Gaffney Strangler, Leroy Martin, who murdered four women in the late 1960s).

HIGH SCHOOL

In addition to the store, Mitchell worked at V. Caggiano & Sons Sunny Slope Farms peach shed, a low-slung building on the outskirts of Gaffney where high school students sorted peaches.

Just as most Aroostook County teenagers help when the potatoes come in, teenagers in Cherokee County would work long hours in the summer when the peaches were ripe.

“If you were a grader, you picked out the bad peaches,” said childhood friend Vicki Roark of Gaffney. “Or you were a ringer, and you would take the prettiest peaches and they would put them on top of the basket.”

Sometimes they worked until 1 or 2 in the morning during the busy season. The girls would come home itchy from the peach fuzz, Roark said.

Mitchell also worked at the counter of a local jeweler during the winter to earn money for Christmas presents.

“I worked because my father expected us to work,” she said. “We were really expected to do our part.”

When she wasn’t at work, Mitchell and her friends spent time at the soda fountain downtown at City Pharmacy and drank cherry Cokes, said Carolyn Gregory, a fellow member of the Gaffney class of 1958.

Gregory remembers “the best barbecue sandwiches for a quarter that you have ever put in your mouth.”

They say Mitchell was a standout student.

“We would be in an English class where we would have to write essays and she would use words I had never heard of before,” Gregory said. “I can bet you I remembered them.”

Football was king, and the girls wore wool skirts and sweaters to every game, even if it was still hot. Rivals Spartanburg and Gaffney played every Thanksgiving.

It was a time of unlocked doors, when parents would yell from the porch when it was time to come home. The downtown, which is now a series of payday loan shops, vacant stores and a few businesses, was safe and bustling.

“It was a time of innocence,” Roark said.

Daniel, who was senior class president when Mitchell was head of the student body, said it was also a time when parents — particularly the Harrills — looked after all children, not just their own.

“Even as a kid, getting to go to Mr. Charlie’s store, that was big,” he said. “(Libby’s) mother and Charlie were just two grand people. They were practically the parents to most of the kids that came in there. They didn’t mind calling your mother or daddy if you misbehaved.”

The Harrill sisters grew up among large extended families, with aunts, uncles and cousins all living nearby.

“If we didn’t have what we needed, we didn’t know it,” Childers said.

COLLEGE YEARS

The Gaffney schools and Furman were still segregated when Mitchell attended. Integration would come to Gaffney a few years after she graduated.

While at Furman — about an hour by car from Gaffney — the school “united” in 1961 by spending more than $2 million on women’s dorms to bring male and female students onto the same campus, according to a September 1961 story in The Furman Paladin, the college newspaper.

“When I started, I started on what was called the women’s campus,” she said. “By the time I graduated, we were fully co-ed.”

It was part of a series of changes at the then-1,600-student college, which was considered one of the top liberal arts universities in the state.

As she was in high school, Mitchell was active in college politics, as vice president of the student body and president of the junior class.

She said the positive experience in high school, where she felt students could make a difference in how things were run, led her to continue to be involved in college. And at Furman, she was able to shape the future of the co-ed university by helping to write the guiding document for student government.

“When we were writing a student government constitution for the new campus, women were so afraid they’d be shut out we wrote ourselves into a second class position,” she said. “We said a woman would be vice president and I was the vice president.”

Three months later, a poll of students showed them closely divided on the question of whether to admit “all properly qualified applicants regardless of race or color,” the newspaper reported. The student vote was 512-432 in favor, while faculty overwhelmingly supported the idea of admitting blacks.

Mitchell said she doesn’t remember the student vote, but does recall that college administrators met with student leaders, including herself, to ask their opinion.

“There wasn’t a single student leader who said anything but we’re totally supportive,” she said.

One summer while in college, Mitchell traveled to Fishkill, N.Y., to serve as a camp counselor for the Fresh Air Fund camping program that was then sponsored by the New York Herald Tribune. The program gave city children, nearly all of them black, a chance to experience the outdoors.

Before she was accepted, she was asked to answer the question: Are you prejudiced?

“I said no,” she said. “And then when I got there I was put to the test because my three roommates were black. The minute we began interacting with one another, I began to see they were more concerned about my reaction to them than I was concerned about their reaction to me.

“All of a sudden we were counselors trying to figure out how to take care of these kids who had never been out of the city. We lived together and worked together all summer. It was a life-changing experience. It wasn’t just a theoretical approach to integration. I was living it and seeing how these young black counselors had been held back.”

Today, that chapter of Southern history is still difficult for people of her generation in Gaffney to discuss.

“This is the part that is so painful to many of us who grew up (in the South),” Mitchell said. “It was the way things were and you didn’t always find it odd. It took a while for you to become sensitive, that this wasn’t right. Why is there a whites-only water fountain? Why are there places that black children can’t go or eat?”

It was also a time when womens’ roles on campus were defined in much different terms than today. For example, here’s an excerpt from the college paper about Mitchell’s crowning as Homecoming Queen:

“Brunette beauty Libby Harrill will be crowned Homecoming Queen, 1961, at halftime ceremonies today …,” the Paladin reported. “The vivacious Gaffney native holds the office of vice-president of the student body this year; she is an active member of Pep Club, serves on President’s Cabinet, and was elected last year to the honorary Senior Order.”

An English major with a political science minor, Mitchell told the college newspaper she wanted to be a teacher or guidance counselor after graduation.

She got her first teaching job in North Carolina, where she taught for two years. She wanted to travel to Europe, so she pursued and landed a job at an international school for girls in Switzerland.

She taught English, U.S. history and civics for a year as the only American teacher at the school.

While she was there, her soon-to-be husband Jim Mitchell was teaching in Beirut, Lebanon. The couple had met months earlier in Washington, D.C., at a “belly dance restaurant” called Port Said, Mitchell said.

The couple married in 1965 and honeymooned in Bar Harbor. After he served in Vietnam, they headed to New Haven, Conn., where Jim was enrolled in Yale Law School.

They came to Maine because a law school professor’s wife was a native of China, Maine. The professor suggested that the couple consider Maine and Mitchell landed a job with Gov. Ken Curtis.

‘SMALL TOWN GIRL DOES WELL’

Mitchell’s high school friends Daniel, Roark, Gregory and Lana Mahaffey of Spartanburg say they weren’t surprised when they heard their classmate was running for governor of Maine.

“It’s been really interesting to hear about her life,” Mahaffey said. “A small town girl does well.”

In 1996, Mitchell became the first woman in state history to be chosen by her peers as House speaker. Twelve years later, she was the first woman in the country to have been chosen both House speaker and Senate president, the second highest political position in the state.

She also went back to law school while in her 60s, and has since passed the Maine bar exam.

Daniel, who served as lieutenant governor of South Carolina from 1983-1987 and ran for governor as a Democrat in 1986, is a lawyer who now works as a lobbyist. He shook his head in disbelief when he thought of Mitchell getting her law degree when she was in her 60s.

“That’s the only thing I would question her on, her sanity,” he said.

“That’s Libby. If there’s something she hasn’t done and she wants to do it, she’s going to try to do it.”

MaineToday Media State House Writer Susan Cover can be contacted at 620-7015 or at:

scover@mainetoday.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.