Since 2010 is the centenary of Winslow Homer’s death, a spate of exhibitions was inevitable. After all, Homer (1836-1910) was not only Maine’s greatest artist, but for a time was also the most acclaimed artist in America.

Homer was enormously influential as an illustrator, printmaker and painter. Largely self-taught, he was tremendously successful at a time when painting was ruled by rigorous convention.

Thanks to his vast professional range, unique standing in American history and unusual subject matter, Homer defies simple understanding. His predilection for depicting popular and domestic culture might make him seem like an intellectual lightweight, but Homer was a figure of singular depth and complexity.

The most important show is the Portland Museum of Art’s “Winslow Homer and the Poetics of Place.” The quiet but luscious installation showcases about 30 works from the museum’s collection.

The most significant portion of the PMA’s holdings are the watercolors that will be given a rest when this show ends Monday. The PMA has also launched a Web site featuring 250 of Homer’s illustrations and published a catalog with a fine (if fancy-worded) essay by curator Tom Denenberg.

“Weatherbeaten” is the star of the show. It is a large seascape in oil on canvas. Under a gray sky, a windswept viridian sea claps its white-tipped waves onto the stolid boulders of the rocky shore. Seething foam recedes to be tossed again as waves to the breakers.

Homer’s nature is wizened but alive with cold fury. He finds beauty not in the picturesque, but in the authentic boldness of the awesome and terrible Maine coast.

“Weatherbeaten” is the Homer we know — the hermit of Prouts Neck. But a few steps away is a painting that leads us towards his roots as the best-known artist in America.

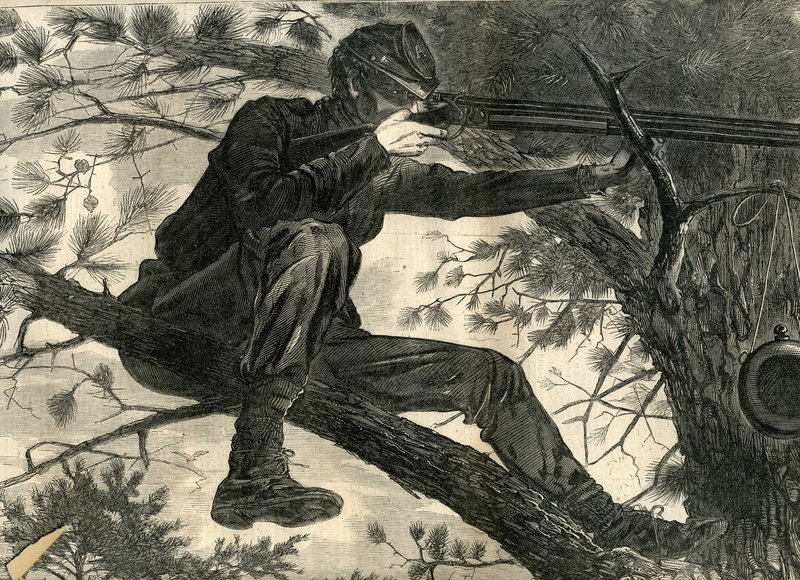

“Sharpshooter” is a small oil painting depicting a Union soldier perched in a tree and aiming through the scope on his sniper rifle. While it was Homer’s first oil painting, it echoes a wood engraving he published in Harper’s Weekly in 1862.

The engraving features the encyclopedic clarity of journalistic illustration: The weapon is seen in perfect profile with the precision of a blueprint. In the painting, however, the rifle is recognizable but vague.

Homer was probably tweaking the abstract qualities of the print’s strong composition. The engraving turns on a pendant-like canteen, whereas the painting solves the balance more elegantly by focusing on the crook of the tree so your eye can travel back up the branch instead of bouncing around. It’s also more human: 1862, Americans were realizing that weapons technology was turning the rebellion into a bloodbath. The print features a gun that could make short work of men, while the painting shows a soldier at his post.

The Saco Museum’s “In a Place by Himself: The Graphic World of Winslow Homer” is illuminating. It features more than 110 prints and books illustrated by Homer. It instantly makes the point that Homer was an extraordinarily prolific artist whose two decades of graphic work was seen by millions. Harper’s Weekly alone had 120,000 subscribers in 1861 when it sent the 25-year-old Homer to camp with the Union army for six months.

We see dozens of Homer’s depictions of soldiers, at war and at play. A violent bayonet charge is shown with the requisite energy, but Homer seemed more excited by soldiers battling in a frenzied game of football. His images of war are myriad, but they reveal an artist more concerned with life than the culture of death.

Many of the 16 works in the exhibition at Colby College depict women either reading or waiting for men to return from sea. A girl reading in a hammock is the very image of self-contained repose.

These sound the universal note of Homer’s work — the subject absorbed in thought. This is why Homer’s illustrations are unusual. Rather than depicting resolving actions, Homer shows moments when the balance might tip either way. In “Tense Moments,” several sailors spy another ship: Is the other vessel in trouble, or is it a menace?

While these exhibitions give us a tremendous portrait of Homer’s talent, they don’t do enough to help us understand his work in context. Did Homer know Baudelaire’s “Painter of Modern Life” published four years before he spent a year in Paris? Was Homer responding to Edouard Manet’s sea paintings? Bastien-Lepage? British watercolorists?

It is easy enough to enjoy Homer’s work as it is, but he shines even brighter in the context of his contemporary culture. Homer’s complexity reveals genius, and we’re often too shy to admit that reality is so complicated.

Colby’s small show features some fresh new donations from the Lunder Collection. The Saco exhibition — although frayed at the edges — presents a compelling view of Homer the graphic artist. The PMA’s show is gorgeous, and should not be missed if you can make it in the next two days.

Freelance writer Daniel Kany is an art historian who lives in Cumberland. He can be contacted at:

dankany@gmail.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.