In late July, when word came down that the Maine Charitable Mechanic Association intended to sell 17 rare hand-painted silk banners made by Portland tradesmen in the 1800s, panic and anger spread quickly throughout Maine’s cultural community.

Outrage might be a better word.

Within an hour of the news breaking, I had three phone calls from bigwigs in the art world. They felt blindsided by the news, and were desperate for a solution.

I cannot recall another time since I began covering the arts in Maine in 2002 when their tone was more pointed or resigned. The idea of preventing the banners from going to auction seemed remote, and they had little hope of mounting a fundraising campaign in time to emerge as highest bidder.

But here we are five weeks later, and the banners are safe and sound. The Maine Historical Society in Portland owns them, offering up $125,350 to emerge as the victor in a late-August auction at the James D. Julia auction house in Fairfield.

A coalition of museums, foundations, corporations and individuals banded together and amassed a pile of money that was large enough to keep the banners in Maine.

It’s one of the great success stories of the year, and says a lot about the level of cooperation among the state’s museums, first and foremost. Lord knows, in any small community there are divisions and differences of opinion, but all were set aside to achieve a common goal. Their success speaks well about the level of cultural leadership in Maine.

Credit goes to seven institutions: Maine Historical, which led the effort; Portland Museum of Art; Maine State Museum in Augusta; Maine Maritime Museum in Bath; and a trio of private college museums, Colby, Bates and Bowdoin.

Most remarkable, perhaps, is the fact that the museums each gave a significant amount of money for something they never will own. Everyone agreed that for the sake of a clean ownership record, it would be best if one institution owned the banners outright, rather than all participating in a shared ownership situation.

Thus, the banners now belong to the Maine Historical Society, although it seems likely they will be exhibited across the state in some sort of cooperative way.

“I think that sort of approach is going to be more common nowadays,” said Amy Lent, director of the Maine Maritime Museum. “Very few museums have six-figure budgets for acquisitions. If we can collectively acquire something that we could not do on our own, we all benefit.”

J.R. Phillips, director of the Maine State Museum, said his institution gave $20,000 from its Heritage Endowment, which was set up with private money to keep state treasures from leaving Maine. “That normally means we buy things to keep in our collection, but it was entirely appropriate to use this money for this project,” Phillips said.

“The thing that strikes me,” said Thomas Denenberg, chief curator at the Portland Museum of Art, “is how fast we got this done. In other states I have worked in, you could not get this level of cooperation, and you certainly could not get it done this quickly.”

Never mind the fact that they got in done in August, the prime month for vacations.

It began with those frantic phone calls, and morphed into a series of meetings to build a strategy and amass funds. Within a few weeks, they had a small pile of money that grew larger almost by the day. building a solid coalition, the group proved to potential funders that they were serious and committed.

Eventually, L.L. Bean became involved, as did the Libra Foundation and a host of individuals.

Their efforts grabbed the attention of the Smithsonian Institution, which sent a political history specialist to the auction in Fairfield just in case. In the event that the Maine museums did not have the financial wherewithal to keep the collection of banners together — some were sold separately, others in a group — the Smithsonian was prepared to play the heavy and scare off private bidders.

But it never came to that. In the end, Harry Rubenstein, chairman of the division of the political history at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History, participated as an interested onlooker.

He praised the effort, calling the result “a wonderful outcome, a perfect outcome.”

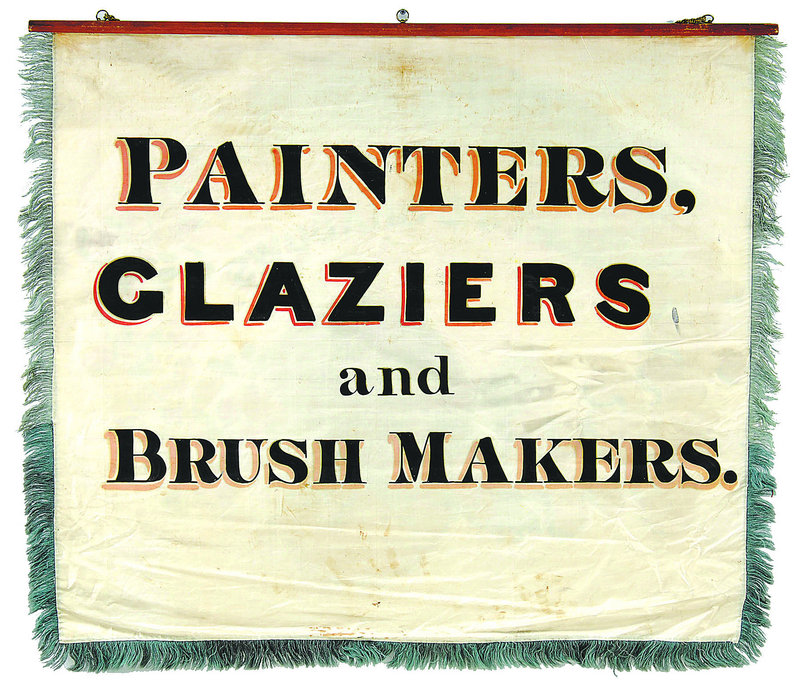

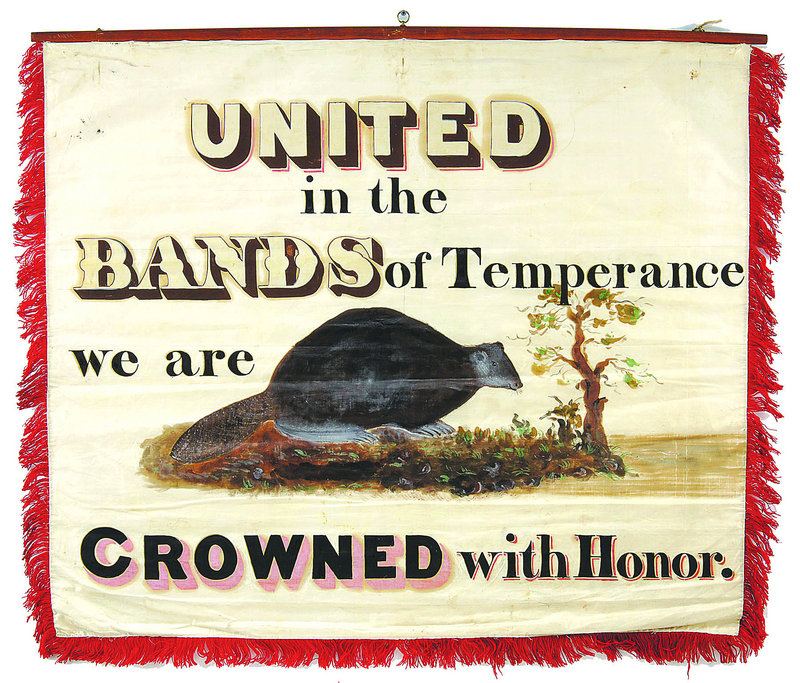

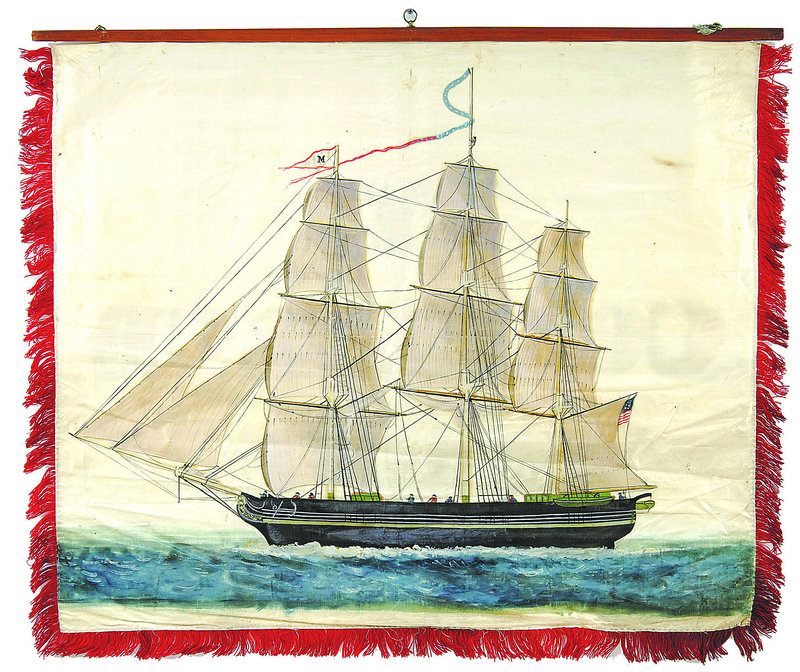

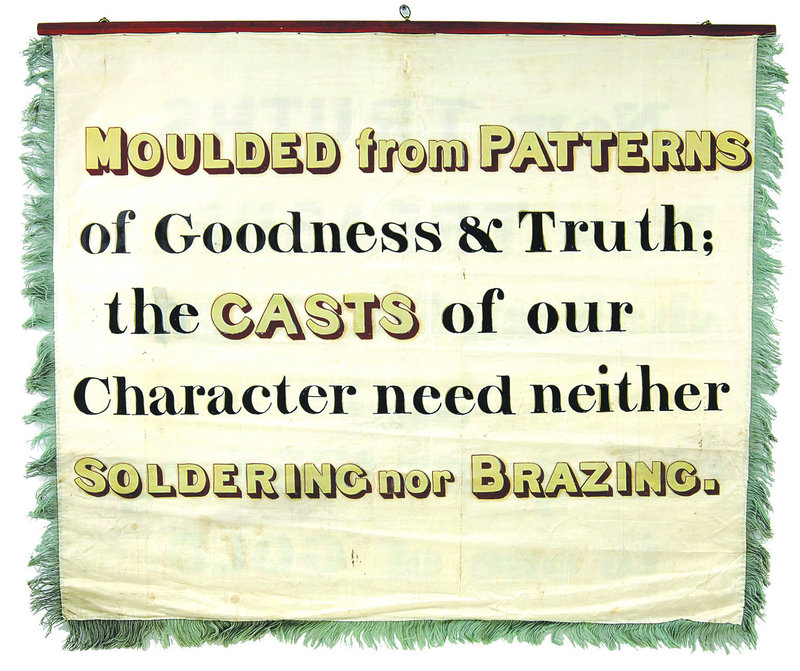

The banners are significant for three reasons. One, because they are rare. Collections like this simply do not exist anywhere. They were made for a Portland labor fair in 1841, with each of the 17 representing the pride and virtues of a particular group of tradesmen.

Two, they are beautiful. They are hand-painted on silk, and the designs are both inventive and stately. Some are laced with humor; each is unique and full of detail that represents a high level of craftsmanship and care.

And third, they represent a uniquely American perspective during the height of the Industrial Revolution. Portland was full of proud workers, and these banners make a bold statement about the workers’ self-worth and their stature in the community.

The fact they’re still here is cause for celebration.

Staff Writer Bob Keyes can be contacted at 791-6457 or at:

bkeyes@pressherald.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.