Seeing John Whalley’s paintings for the first time can be an astonishing experience. They have all of the details of photographs and yet none of the distortions of the photographic process: no lens flares, no burned-out or underexposed areas, no overarching circular bend caused by a round lens.

Whalley’s “At Hand” is an oil on panel from his exhibition, “Timepieces,” at Greenhut Galleries in Portland. It features an ancient and well-experienced screwdriver placed on a wizened metal case once covered with denim. The fabric has been completely worn away at the edges of the small shaving kit for so long that the once-covered metal has now been alternately dinged and burnished. These objects are seen centered on a similarly-aged metal surface that ebbs and flows between rusted metal and the paint that once covered it completely.

What is shocking about this — and pretty much every other work by Whalley — is the sense of detail. The strength of his drawing usually leads viewers to think Whalley’s virtuosity lies in his draftsmanship, but we too often confuse brilliant mark-making with teachable technique. And Whalley’s gifts cannot be taught.

When we look again at “At Hand” to consider the extent to which drawing drives the painting, we see draftsmanship is minor in this work, while texture is virtually everything. The tool is so worn that the only way to feel the different materials is through the coolness of the metal as opposed to the wood. We feel the fabric on the case, the roughness of the rusted surface and the smoothness of the worn edges. Observation for Whalley is hardly photographic opticality; it is physical reality.

One of my favorite works from “Timepieces” is a graphite drawing of three forks on a worn plate. Once again, the work is centered symmetrically and seen from directly above. The center fork is the largest with four tines, while the bracketing others each have three. All four objects are ancient and outdated, and they were clearly used for decades on end. To this end, they hint of a simple poverty that would value such basic objects for so long. Yet by being so arranged, we see them as objects of quiet meditation rather than the utensils of our own dinner.

The angle of the image, however, is oddly close to the perspective of looking down on one’s own plate. The distance is personal, but the view is more like that of a microscope.

I think people are usually so blown away by Whalley’s technique and the sheer beauty of his compositions that they almost inevitably miss the fundamental conceptual point of his work: observation is an issue of cultural philosophy.

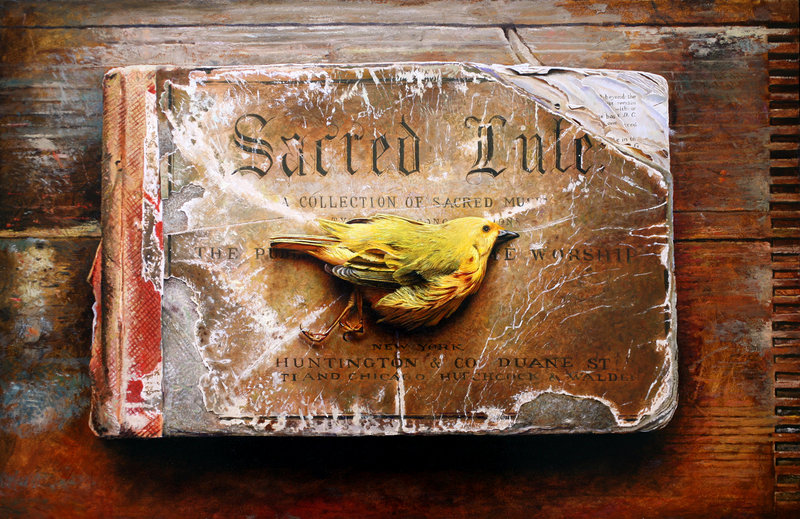

Some of my favorite new works by Whalley are the three that feature small birds lying on books. In the spirit of James Audubon, they appear to be dead but are lovingly rendered. But whereas Audubon’s goal was the scientifically objective information of the Enlightenment, Whalley’s takes the opposite tack and infuses his birds with a Romantic spirit. Two are sweet little finches placed on musical texts; one on a score titled “Farewell” and the other gently laid upon a book for “Sacred Lute.”

Surprisingly, these pieces are free of nostalgia. Their melancholy is bittersweet, respectful and somehow uplifting, as though we might sense goodness in ourselves for caring about these tender bits of nature past.

We often forget that Romanticism is deeply concerned with observation. It differs from Enlightenment/scientific observation by valuing the personal (the subjective) observation over the impersonal (objective) oculus of scientific method. Whalley is undoubtedly a Romantic.

One interesting twist of “Timepieces” is that in addition to his pictures, Whalley presents many of the actual objects depicted in the show in a single glass display case at Greenhut. While I wish he hadn’t done that, it absolutely clarifies Whalley’s affinity with the master of assemblage, Joseph Cornell, as opposed to the trompe l’oeil champions like Harnett or Peto. Cornell’s gorgeously delicate sensibilities flowed quietly through seas of obsession and powerful insistence. The same must be said of Whalley. His work is memory-worn and perfected through seemingly countless hours, but it is so often even heartbreakingly beautiful.

With the calm and patient mastery of his craft, Whalley respects the viewer, and we cannot help but be charmed or even flattered. This has always been the case with Whalley. Associated with a 1981 tempera painting, his graphite drawing of a carpenter — one of his three works in a fabulous drawing show at the University of New England’s Portland campus — is huge (20 by 30 inches), and took him more than a month to complete.

Time will always be an issue for Whalley. It can take him a month to make something seemingly momentary. He puts in so much work that you get it in the blink of an eye.

Or do you? While I believe all you have to do to understand Whalley’s paintings is look at them, the ease of this experience does not mean they are anything less than brilliant.

I have been looking at his work for a long time, and it only gets better.

Freelance writer Daniel Kany is an art historian who lives in Cumberland. He can be contacted at:

dankany@gmail.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.