WATERVILLE – Sharon Lockhart, a conceptual artist from Los Angeles, delved into the bowels of Bath Iron Works for her latest exploration, “Lunch Break.”

With film, photography and a collection of labor-related items and artifacts created by the workforce at BIW and from across Maine over time, “Lunch Break” celebrates the skills and commitment of Maine’s labor force. It focuses on the activities of present-day blue-collar workers at the ship-building giant in Bath, and presents the workers in a heroic light, setting them up as conquerors against the odds and, to a lesser degree, defenders of the nation.

“‘Lunch Break’ is a project that recognizes Maine workers for their skills and creativity, as well as their self-reliance and dignity,” says Elizabeth Finch, the Lunder Curator of American Art at the Colby museum. “It also acknowledges the long local history of those qualities and, by extension, a sense of community, past and present.”

The show is on view at the Colby College Museum of Art through Oct. 17.

Lockhart, who was born in Massachusetts in 1964 and has family in Maine, spent the better part of a year at BIW and other plants and factories in Maine in 2007 and 2008. Her purpose was to observe, talk to and hang out with the workers during their shifts and breaks.

She was interested in getting to know them individually and collectively, and then using her friendships and knowledge to illuminate the lives of these laborers in such as a way that the rest of us gain a measure of appreciation for their daily grind.

WINNING WORKERS’ TRUST

On a more basic level, “Lunch Break” offers viewers a glimpse inside the plant. Access to BIW is highly restricted, and Lockhart worked hard to gain permission to spend time inside the yard. After receiving permission, she had to win the trust of the workers.

Her exhibition is smart and sophisticated and, perhaps its greatest triumph, not at all pedantic or didactic, and certainly not pretentious. With her photography and two captivating films, as well as her complementary choices from the Colby collection and loans from other museums in Maine, she offers a humanistic portrait of the Maine workforce, devoid of drippy romanticism.

“What she is trying to show is a continuum of the skills and artistry and creativity of the past to the present day among workers in Maine,” Finch said.

She does so in several ways.

The bookends of “Lunch Break” are two films, one checking in at 80 minutes and the other at 40 minutes. In the first, also titled “Lunch Break,” Lockhart’s camera moves ever-so-slowly down a long corridor in the plant’s Assembly Hall, which is marked by fluorescent lights, industrial tubing and wires, and rows of lockers.

The hallway extends down an endless narrow path, and is populated by men and women on break. Some are seated reading newspapers; others stand while talking in clusters. Some eat snacks. Others nap.

The other film, half as long at 40 minutes, is titled “Exit.” Lockhart fixes a static camera at the yard exit and captures the workers as they depart the grounds after their shift. She films for eight minutes on consecutive days, Monday to Friday.

Patterns of human repetition present themselves instantly. The workers, mostly burly men, walk with a laborer’s gait. Many have pronounced limps. They swing their lunch pails in unison and talk in measured, hopeful tones. Their pace is quick; most bolt from the yard like students released from school. Others move slowly.

But all are focused on the single purpose of leaving work.

UNIFYING THEME

The photography in this show comes in three varieties. In several large-scale color prints, Lockhart simply captures men during their breaks. They are seated around a picnic bench, smoking cigarettes beneath a hand-written sign that once said “No Smoking,” but the word “No” is painted over. One guy sits off on his own, working on a newspaper crossword puzzle.

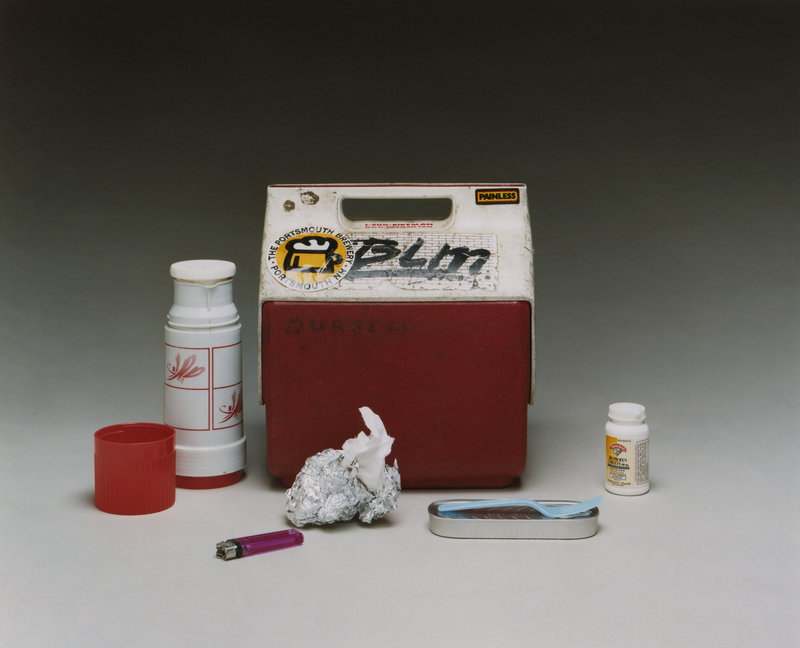

A second series includes still-life color images of the workers’ coolers and lunch pails. A unifying theme of the workers’ days is their common break, and the central element of their break is their food.

We can tell a lot about the men from studying the contents of the coolers. Case in point: Gary Gilpatrick’s black lunch pail is adorned with stickers bearing the name of completed Navy ships. We know that Gary is a long-term employee, because his pail displays stickers from many ships.

Among the items he has in his box are the daily newspaper, with a bold headline proclaiming economic doom. The paper is folded in quarters, so we cannot read the entire headline, but the implication is ominous: “Wall Street have fallen,” it partially reads. He’s got a sharpened pencil and magnifying glass, both presumably for the crossword puzzle. He also carries three plastic bottles of prescription drugs and a pack of Marlboro Ultra Lights.

Stephen Bade, an electrician at the plant, uses his cooler as a billboard for his humor. He’s got one sticker that says, “Work is the curse of the drinking class” and another that says, “Save a cow eat a vegetarian.”

Perhaps the most revealing element in Lockhart’s show are her photographs of many private independent businesses that operate within the BIW complex. Many workers have outfitted their lockers to serve as private convenience stores.

During breaks, co-workers drop coins into a cup on the honor system to buy candy bars, bottles of water, even steamed hot dogs.

These businesses operate entirely independently of BIW itself, and are the sole responsibility of the individual workers who choose to double as proprietors. They have names like “Dirty Don’s Delicious Dogs” and “The Pipecoverer’s Cafe.”

ALSO IN THE EXHIBIT . . .

To supplement the show, Lockhart has borrowed heavily from Colby’s collection and other museums, including the Maine Maritime Museum in Bath and the Maine State Museum in Augusta.

She was interested in showing Maine-related crafts made by laborers, and has included ashtrays, smoking pipes, a cribbage board, a pair of stainless-steel barbells and a box of fishing lures, among other things.

In a nod to the workers she honors, Lockhart and co-collaborators Frank Escher and Ravi Gunewardena created a series of display cabinets for the material, and decided to put the workers’ creations under glass along with the pieces on loan from other museums so they are presented equally.

She also displays a lot of artwork by established artists. There’s a Winslow Homer illustration from Harper’s Weekly in 1868 showing New England factory life. The engraving shows workers — in this instance, mostly women — departing a Massachusetts mill after the work whistle signals the end of the shift. Most are holding lunch baskets in their arms.

Although they were made almost 150 years apart, Homer’s static image very closely resembles the action in Lockhart’s “Exit” film.

There are photographs by Chansonetta Stanley Emmons of early-20th century farm life, drawings by Andrew Wyeth and Alex Katz, paintings by Marsden Hartley, George Bellows and Neil Welliver, and sculpture by Louise Nevelson.

Appropriately, the final image in the show is a 17th-century engraving by Israel Henriet, depicting a lone figure seated on the ground.

It is simply titled “Man Resting.”

Staff Writer Bob Keyes at 791-6457 or at: bkeyes@pressherald.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.