The Colby College Museum of Art has a particularly interesting slate of shows on view. Sharon Lockhart’s new “Lunch Break” is an enormous installation of unusual scale and range that includes film, photography and found and borrowed objects. There is a gem of a Whistler show. There is also a show of 16 works by Winslow Homer.

Considering the star power of Colby’s other exhibitions, I was surprised to be most impressed by a small exhibition of sketches along with related prints and copper plates made by Will Barnet in the 1930s.

Barnet is best known for his elegantly stylized and calmly reposed portraits and domestic scenes rather than his earlier representational works, which tend towards brooding — unlike this body of work with its romantic, even passionate, demeanor.

Although they were previously published, the sketches on view at Colby are being displayed for the first time. They are loose and quick drawings mostly made in New York’s Central Park, where Barnet spent a great deal of time. They float between observation and constructed compositions.

The sketches show Barnet making stylistic decisions in the wake of Picasso, Matisse and Fernand L?r (who, through the 1920s, was the most famous artist in Paris). “Repose” (1934) unabashedly follows Matisse’s light and flickering draftsmanship.

Barnet is less successful in employing a Picasso-esque graphic style in “Luncheon” and his “Family” sketches. This is not surprising. Picasso’s style looks classical, but seeks to establish a complicated relationship between simple-appearing lines and darker areas of weight and density.

Barnet’s most successful of these drawings are those in which he follows the clarified volumes of L?r. While Barnet switched to focus on flat shapes instead of volumes in his later works, the simpler works here achieve a calmer feel and more balanced compositions.

Several of the sketches come together in groups to reveal the artist’s thought process. A particularly interesting group starts with a sailor and a young woman. In a later sketch, another couple — kissing — appears between them, probably as a phantom of the pair’s desires.

the final print of “The Kiss,” the sailor and the woman have been relegated to secondary importance to each side of the embracing couple. Alone, “The Kiss” is a little strange because of the claustrophobic proximity of the onlookers to the lip-locked pair. But in the context of the drawings, it is sweet and interestingly complex.

Romance is the major theme of the show, as most of the titles tell us: “The Kiss,” “Passion,” “Affection,” “The Couple” and so on.

The images related to the L?resque “The Lovers” include a highly finished sketch (complete with notes on colors, which proves it to be a sketch for a painting rather than a finished drawing) as well as an etching and the copper plate from which it was pulled. The set reveals the odd fact that Barnet’s early images are almost always weaker when reversed as prints because of the left-to-right reading logic of these sketches.

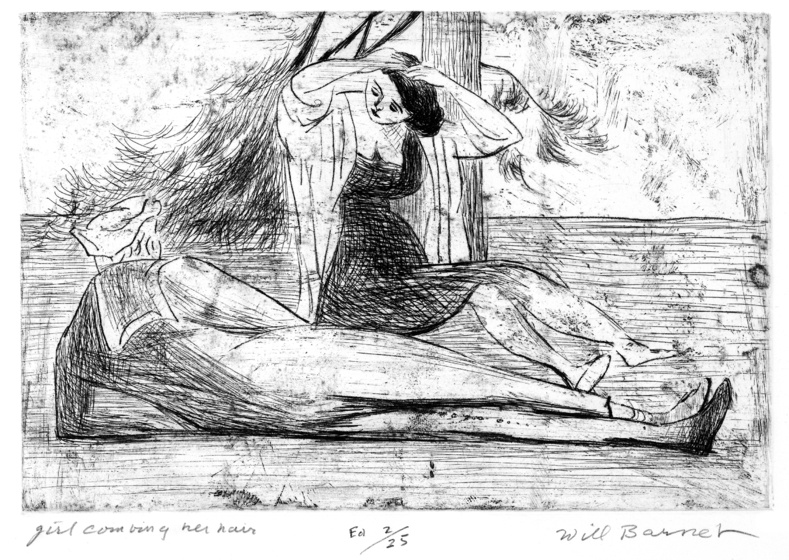

In “Girl Combing Her Hair,” the recumbent sailor would far better anchor the etching if it were not reversed. In the “Affection” works, the drawing has a far warmer feel when the woman appears from the left. In the print, in which she appears on the right, she seems stilted or even stiff.

One of my favorite works in the show is “Father and Carriage.” The father is turned to his right over a baby carriage. The outline of his head, neck, shoulder and arm is not only divine, but it sets the logic of the entire composition: The voluminous figure of the mother is comfortably reclining on the grass in the right side of the image, and within her form is a tilted parallelogram that illustrates the geometrical mapping shift in the piece from stylized outline on the left to recumbent volume on the right.

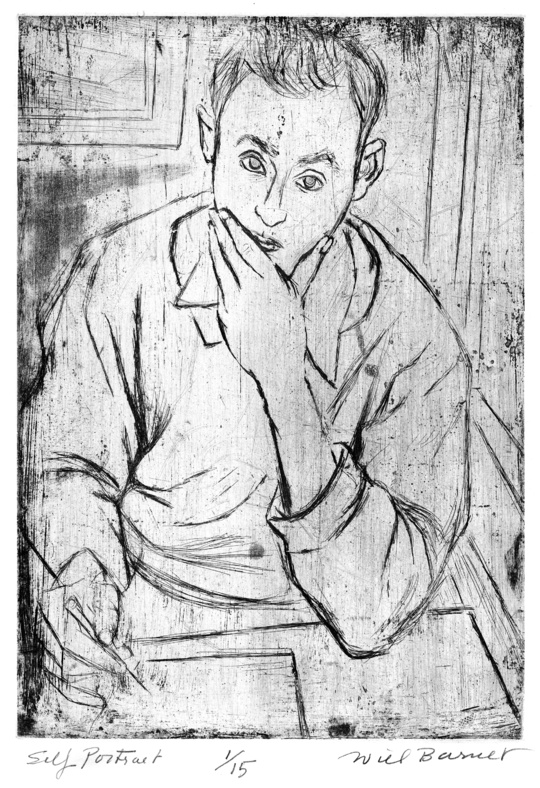

The show also features a self-portrait etching. A young Will Barnet examines himself in the mirror, for which the viewer is now substituted. The idea is terrific: He sees himself reversed in the mirror and makes a direct drawing on a copper plate that will be reversed when printed.

With all the big-name shows at Colby, it would be easy to pass by the Barnet show. Don’t.

Freelance writer Daniel Kany is an art historian who lives in Cumberland. He can be contacted at: dankany@gmail.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.