AUGUSTA – Civil War 2nd Lt. John W. Dana spent a safe — and apparently uneventful — July 4 in 1862 while stationed in New Orleans as a member of the 12th Regiment, Maine Volunteer Infantry.

“We enjoyed the dullest Fourth yesterday that I ever knew,” he wrote to his father. “Oh! You’ve no idea of it. But I suppose you had great times in the North.”

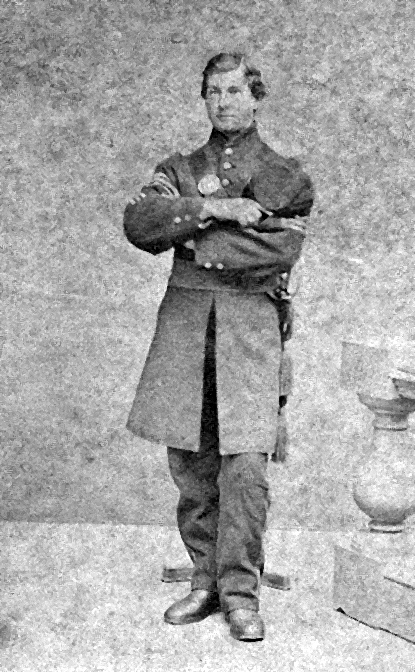

At age 18, Dana, a distant relative of Maine Gov. John W. Dana (1847-1850), enlisted as a sergeant major. It was Oct. 1, 1861, and the sandy-haired, blue-eyed soldier from Maine spent the next three years as a Union soldier serving in the South.

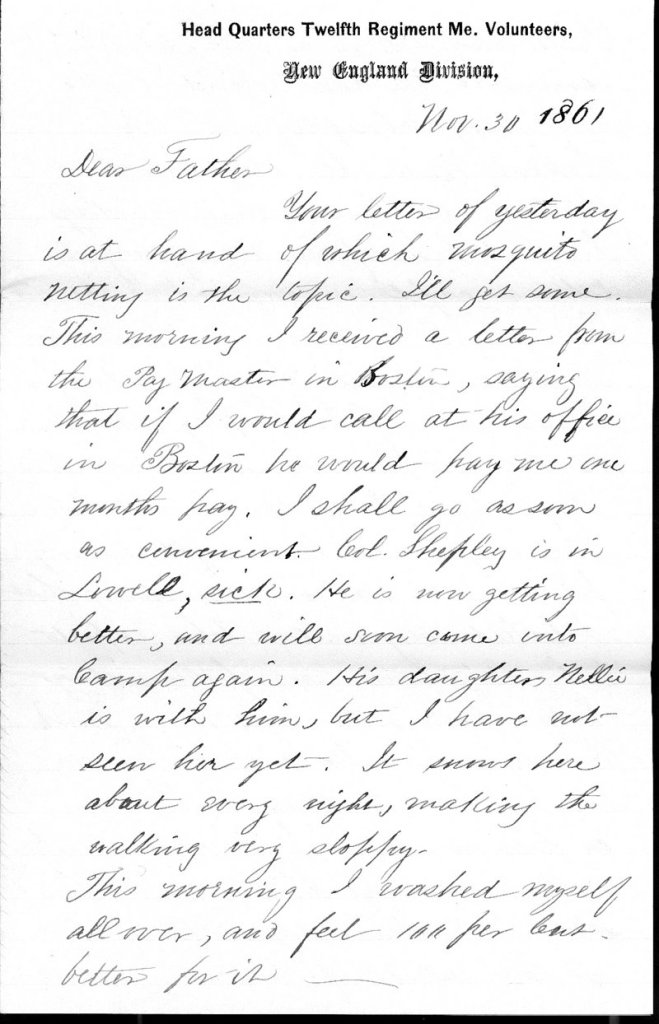

Although his service didn’t include major battles fought in Virginia and Pennsylvania, his detailed letters home paint a picture of what it was like to be a young man in the war — from time spent as a prisoner to tales of gambling, drunken nights and speculation about how long they would be at battle.

The Maine State Museum bought the collection of 163 letters and documents at auction in April for $9,660. The state used endowment funds that come from donors to make the purchase.

Laurie LaBar, chief curator of history and decorative arts, said that, to collectors, the letters may seem less valuable because they don’t highlight well-known battles.

But to the museum, Dana’s insights offer something different.

“In a lot of ways, to my mind, it makes this collection more desirable that it was about his daily life and what he thought about and was feeling. It wasn’t just the battles,” LaBar said.

The letters also show just how far Maine soldiers were sent during the war, said Kate McBrien, curator of historic collections.

“There were so many of them being sent to war, and who were willing to fight, they were scattered across the country,” she said. “This helps to show an area of service in the Civil War that our collection doesn’t show yet.”

Part of Dana’s story includes time spent in a prisoner-of-war camp.

“Partway through the war, he was captured by the Confederates,” McBrien said. “He wrote letters during that period, maybe slightly cleaned-up letters, because the Confederates would have been reading them before he sent them out.”

LaBar said Dana would have been treated better as a prisoner than enlisted men because at that point he was an officer — a second lieutenant.

“For the enlisted men, the camps were pretty horrific,” LaBar said. “They were really concentration camps. When you factor in mosquito-borne illnesses and all that, it was really horrific for the enlisted men. The officers had it a little bit better.”

Records in the state archives show 239 members of the 12th Regiment died of diseases such as yellow fever or malaria while only 52 members were killed or died of wounds.

The museum has hired an intern — Colby College senior Jennifer Babb — to make copies of each letter to preserve the information, should anything ever happen to the originals.

The museum will eventually make the collection available to researchers, and it will be part of an observance of the 150th anniversary of the war that begins in 2011.

In late June 1862, Dana wrote a letter to “Aunt Derring” that described his work as a member of a signal party.

“Think of standing all day in a terribly hot sun, looking through a telescope at a flag waving 10 or 15 miles off,” he wrote. “Several lieutenants of our regiment were jealous of me because they thought me too young, but that makes no difference. I intend to show them if chance offers that I’m not too young — I was out most of last night signaling with torches, and today am slightly fatigued.”

He then goes on to say he likes New Orleans.

“The citizens have become perfectly docile now, and a federal officer can walk the streets without being insulted, though we still have to wear our arms, whenever we go out. It is awfully hot, but I stand in first rate and have not had a sick day in the South, tho’ I’ve often felt mizerable.”

He signed the letter “Ever your affectionate nephew.”

Dana was eventually promoted to the rank of captain and resigned from service in July 1865. He died 46 years later in Falmouth Foreside.

The collection includes a large discharge certificate signed by Gov. Samuel Cony.

In his letter dated July 5, 1862, Dana further describes what his holiday was like in New Orleans.

“Cannons were fired at sunrise, midday, sunset and the band played in the morning, evening, but there was no such feeling as is manifested in every city of the North,” he wrote.

MaineToday Media State House Reporter Susan Cover can be contacted at 620-7016 or at:

scover@centralmaine.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.