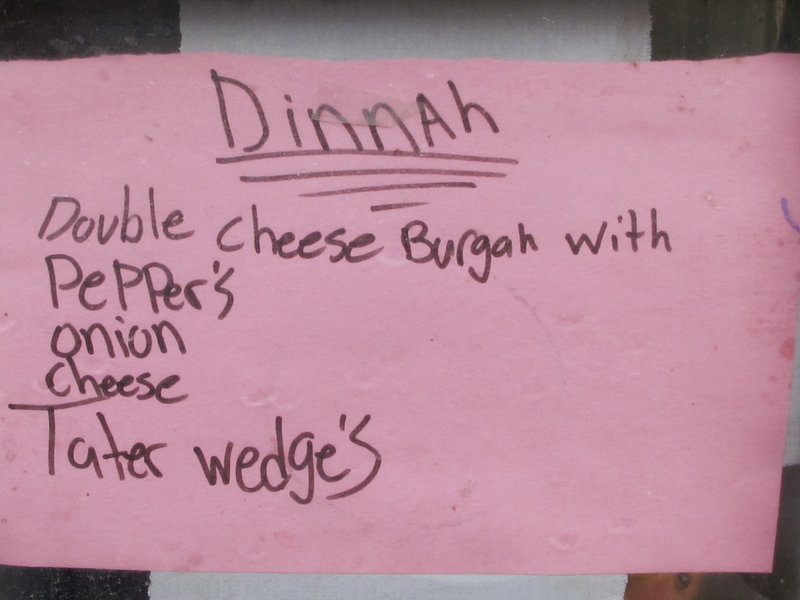

COMBAT OUTPOST DAND WA PATAN, Afghanistan – The half-cooked burgers, at least two dozen of them, pop-pop-popped on the hot electric grill.

The onions and peppers sizzled somewhere between al dente and saute.

The clock indicated 15 minutes, and counting, to chow time.

Spatula in hand (flip, flip, flip, flip scrape, scrape flip, flip, flip, scrape flip, flip, flatten and scrape ), Spc. Jeffrey Pelletier of Waterville moved like a soldier on a high-priority mission inside his hot, cramped Army kitchen.

Then it happened.

The massive generator out back coughed, sputtered and, just like that, died.

In this place where the roar of generators means all is well, the sudden silence was deafening.

“Uh-oh,” Pelletier said, spatula suspended in midair. “That’s not good.”

Without missing a beat, the baby-faced cook rushed outside, flipped open the lid of a makeshift, 55-gallon-drum outdoor grill and quickly ignited a roaring blaze from scrap lumber.

“We’ll barbecue the rest of them,” he said, cool as a cucumber.

You want pressure in a combat zone?

Try being the only cook for 150 young, strapping, always ravenous soldiers from the Maine Army National Guard’s Bravo Company, 3rd Battalion, 172nd Mountain Infantry.

“It’s a pretty daunting task,” Pelletier said during a rare quiet moment this week. “Ideally, you should have one cook for 50 soldiers. So there should be at least probably two or three cooks here.”

Instead, there’s Pelletier. And there’s Pfc. Kevin Beal of Machias, who helps out with the serving and the stocking while the boss focuses on the one thing that truly matters to any GI who’s toughing it out here on the Afghanistan-Pakistan border: his stomach.

Pelletier is 27. A decade or so ago, he was best known as the kid from Palermo who knew his way around engines and raced stock cars at tracks in Wiscasset and Unity.

Then, after he graduated from Erskine Academy in South China in 2002, life came knocking.

Pelletier broke up with his girlfriend, joined the Army and, just for the heck of it, decided to try cooking.

Smart move.

After finishing his advanced individual training as a food service specialist and, on the military’s dime, taking an intensive three-week course at the Culinary Institute of America, Pelletier soon came to realize that he was more than just interested in cooking. He was pretty darned good at it.

So good that by 2004, at age 20, he was named the National Military Pastry Chef of the Year — besting every other cook in the Army, Navy, Air Force and Marines when it came to all things crusty-yet-flaky.

Posted in Korea at the time, Pelletier soon found himself transferred straight to the top — the secretary of the Army’s dining facility at the Pentagon.

There, over the next three years, he cooked for generals, senators and congressmen.

He cooked for visiting military brass from the Mediterranean and all over the Middle East.

He even cooked for celebrities like former football star Terry Bradshaw, baseball legend Dave Winfield and World Wrestling Federation idol “Mankind” — each of whom posed for pictures with Pelletier at the annual Hall of Heroes banquet for wounded veterans in Washington, D.C.

So how does a young guy, well versed in the intricacies of truffles and creme brulee, end up at a hardscrabble combat outpost churning out cheeseburgers, bacon and eggs and chicken tenders?

For starters, Pelletier finished his four-year active-duty hitch in 2007 and immediately joined the Maine Guard.

But there was more to it. As exciting as his active tour of duty had been, it left him with a nagging feeling that he’d never actually been, well, a real soldier.

“The only reason I joined the National Guard was to deploy, because I hadn’t deployed when I was on active duty,” he said. “It kind of made me feel incomplete, like I hadn’t done my job.”

At the risk of understatement, that is no longer a problem.

Few if any soldiers in Bravo Company work harder, longer and with a more consistent smile than the guy with the 10 large metal food connexes (eight dry, two refrigerated) filled with everything from muffins and breakfast cereal to chicken breasts, broccoli and, yes, those really are frozen crab cakes.

Pelletier’s typical day begins at 4:30 a.m. and ends, without a break, sometime between 7 and 8 p.m.

In between, he’ll cook breakfast, lunch and dinner for 100 to 150 men — depending who’s here and who’s out on a mission. That, on a busy day, can mean close to 500 meals.

And often it doesn’t end with dinner.

While his fellow soldiers toss their paper plates and plastic utensils in the trash and head for the gym or the nightly video-game competition, Pelletier drags himself over to Bravo Company’s tactical operations center, logs on to a computer and fires off his next two-week food order to battalion headquarters.

Or he’ll head for his bunk, pull out his notebook and brainstorm menu ideas.

“Waking up in the morning is the hardest part — actually getting my feet on the ground,” Pelletier said. “There are some mornings where I’m just like, ‘Man!’ “

So can’t he sleep in on his day off?

“There is no day off,” Pelletier said. “I’m the only one here.”

OK, then how about the occasional sick day?

“You can’t ‘call in,’ ” he said. “If I don’t come in and do this, number one, I’m going to get my ass chewed and, number two, nobody’s going to eat. So you’ve got to take care of the troops so they can protect you.”

Ask him the date or day of the week, and Pelletier will answer with a blank stare. It got him into trouble — big trouble — on Easter Sunday.

“I didn’t know what day it was,” he said. “Honestly, I swear to God.”

Meaning?

“Corn dogs.”

Ouch.

“Guys were like, ‘Are you serious, man? It’s Easter!’ ” Pelletier recalled. “And I’m like, ‘What? Easter? Oh, my bad.’ Honestly, I wouldn’t have done that if I had known. I mean I actually had hams!”

He wasn’t the only one with Easter egg on his face: Bravo Company’s official holiday meal — a 70-pound roast beef — arrived two weeks later. Pelletier, in an act of pure redemption, slow-cooked the roast for an entire night and then hand-carved it in the mess hall for his salivating comrades.

Workload aside, what weighs on Pelletier most heavily is the lack of time and ingredients to turn chow time into, as the food critics might say, an unforgettable dining experience.

Still, his work doesn’t go unappreciated.

Danny Wiltsie of California and Ryan Cottle of Alabama work for a military contractor and spend their time traveling throughout the Afghanistan theater training soldiers on force-protection systems.

In other words, this nomadic duo knows military food — from the good to the so-so to the downright dyspeptic.

“For COPs (combat outposts) and smaller FOBs (forward operating bases), this is by far the best chow we’ve had,” Wiltsie said as he and Cottle loaded up on burritos at the serving window Wednesday. “This guy’s got ’em beat hands down.”

Pelletier nodded his appreciation to his newfound fans. And moments later, his day got even better.

Spc. Nate Allen of Portland showed up at the kitchen with a plastic bag in hand. This week’s mail call included a care package from Allen’s dad in Detroit — and the package included a bag brimming with big, fat cloves of garlic.

“The only thing I could think of was to bring them here,” Allen said.

Pelletier’s eyes opened wide. Fresh garlic. Right here. In the middle of a war zone.

Thanking Allen profusely, the young cook — check that, experienced chef — took the bag and set it down ever so gently on his counter.

Dinner, for once, would be different.

“Garlic,” Pelletier said quietly. “Sweet!”

Columnist Bill Nemitz can be contacted at 791-6323 or at:

bnemitz@pressherald.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.