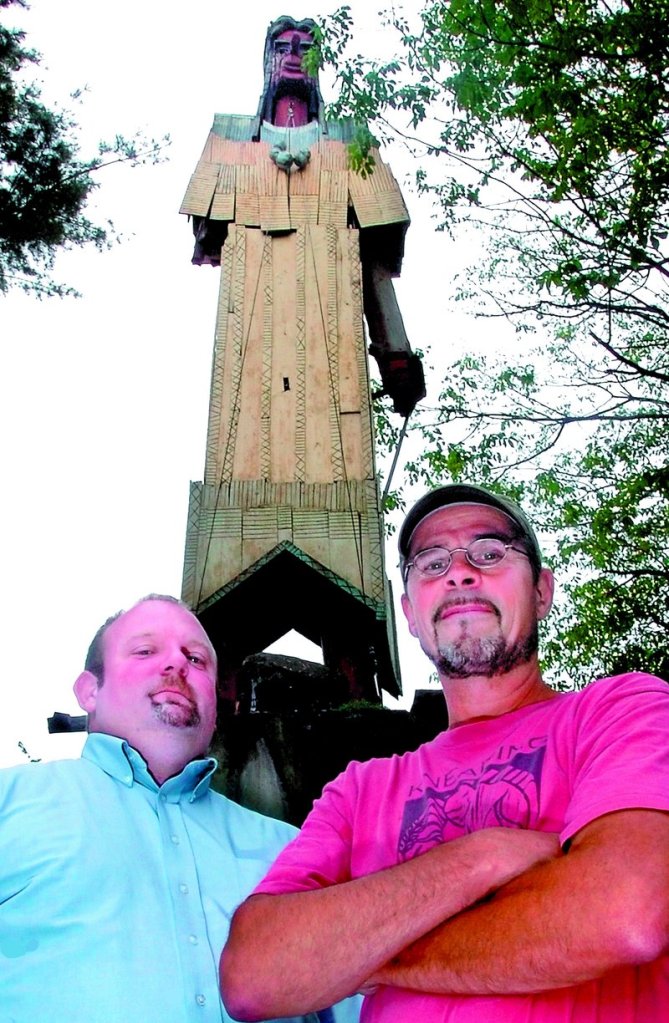

SKOWHEGAN – For 41 years, the Skowhegan Indian sculpture has stood over downtown, a towering symbol of a time long ago when indigenous people hunted and fished along the waterways here.

But now, the 62-foot-high work by renowned artist Bernard Langlais has fallen on hard times.

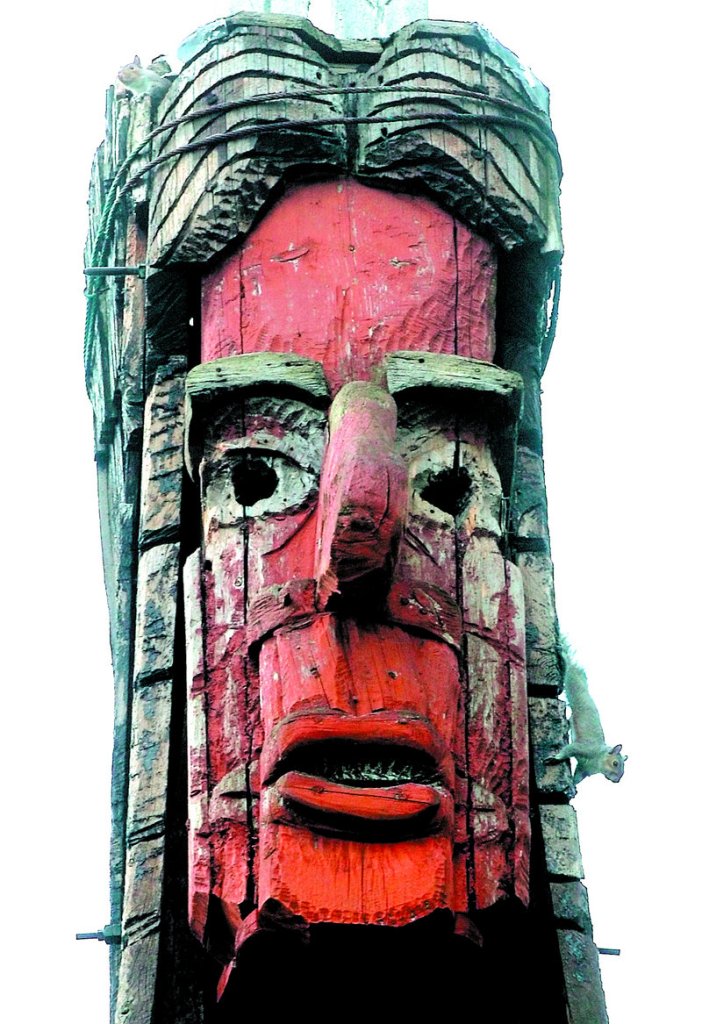

Its right forearm and hand are rotted, parts of the left hand and foot need replacing, paint is peeling, and squirrels and pigeons have commandeered it.

The Skowhegan Area Chamber of Commerce, which owns the sculpture, is stepping up efforts to raise money to restore the Indian, built by Langlais over three years and erected in 1969.

“We want to get this rolling before we start losing more of the sculpture,” says Cory King, the chamber’s executive director. “It’s gone far enough. It’s not the best time, economically, to start fundraising for something like this, but we also can’t afford to wait any longer.”

The chamber has about $22,000 from fundraisers for restoration, but about $45,000 more is needed, according to King.

The 24,000-pound Indian, made largely from white pine, is not in danger of falling over. Two steel I-beams inside the concrete base extend inside the sculpture to its shoulders to support it, according to experts.

“In my opinion, only about 7 to 9 percent of the sculpture needs serious work, either by replacing or rebuilding or consolidation with epoxy; so it isn’t all gloom and doom,” said Stephen Dionne, a Skowhegan builder, architectural woodworker and restorer chosen to do the work.

“If nothing is done, it’s just going to continue to deteriorate like an old building would. It’s the size of a six-story building. It will just, over time, continue to wear away.”

The restoration and preservation effort requires special scaffolding that will be expensive, according to Dionne. An estimate about four years ago was more than $15,000, he said.

Work on the sculpture also requires a delicate balance.

“You want to do as little as possible, but at the same time, preserve it,” said Dionne, whose history with the artwork goes back several years. “At all costs, pretty much, you try to keep what is original and not replace.”

THE SCULPTURE’S HISTORY

In 1966, the Skowhegan Tourist Hospitality Association, the precursor to the chamber, commissioned Langlais’ sculpture in memory of Maine Indians, “the first people to use these lands in peaceful ways,” according to a sign at the base of the sculpture.

Langlais, who grew up in Old Town and was a student and teacher at Skowhegan School of Painting & Sculpture, worked on the piece at his Cushing home. The sculpture was erected in 1969 off Madison Avenue, behind where Cumberland Farms now sits.

Langlais was born in 1921 and died in 1977; his wife, Helen, who grew up in Skowhegan, died recently.

Back in the 1960s, the tourist association borrowed $20,000 for the sculpture and later gave the Indian to the town. It was later given to the chamber.

There were initially big plans to develop a park around the sculpture. But the plans never materialized and businesses were built nearby.

Trees near the Indian have grown so large their branches obscure the piece. Over the years, debate about moving the Indian to a more visible location cropped up. And money was raised to fix problems plaguing the sculpture.

ONGOING REPAIR

Repairs were undertaken after a structural engineering study in 2004.

Bird nests were removed from the structure and the concrete base cleaned of bird droppings and soil, and then pressure-washed, according to Dionne’s records. A special solution was applied to the Indian’s legs, feet and other features to deter decay; and special screening was stapled to the underside of the hollow sculpture to keep out birds and squirrels.

Stainless steel guy wires were installed to increase stability. Paint samples were sent to a conservator in Virginia for analysis.

Parts of the sculpture, including the right arm, hand, weir assembly and spear have been removed for Dionne to work on.

A 21-item list of needed repairs includes hand-sawing and kiln-drying replacement parts for sections of the right arm and hand, left hand and left foot; harvesting logs from the forest and kiln-drying them for replacement in the weir; and trimming or removing trees near the sculpture.

The interior diagonal brace of the sculpture is broken and must be replaced along with several other parts; rusted bolts and flashing must be replaced with stainless steel pieces; and all accessible steel sanded and painted. The entire sculpture needs to be cleaned, scraped, sanded and painted. The sign at its base also needs repair and paint.

PRESERVATION PLEAS

Sharon Corwin, director of the Colby College Museum of Art, sees Langlais’ position in Maine art and American art as a great one and his Skowhegan sculpture, a treasure.

“Anything that the community can do to save it would benefit arts in Maine,” Corwin said. “There are so few of his sculptures left in public sightings.”

The wood sculpture is part of Skowhegan’s identity, according to Corwin.

“I think it’s a wonderful piece of art.”

Dionne, who has worked with preservation architects on structures such as the Skowhegan and Oakland public libraries and the Skowhegan History House, also cites the importance of preserving the piece.

“I went to Colby when Bernard Langlais’ show ‘The Middle Years’ was there,” he said. “I was really struck by some of the things he’s done in the past. I realize how important this piece of art (the Indian) is because he didn’t do anything else on this scale. This is by far his largest piece of work.”

King, of the chamber, hopes that the community will rally to fund the project and possibly start an endowment for future maintenance. A bike rally to benefit the sculpture is scheduled for July 17. Grants will be pursued, King said.

“Maybe this is something that can coalesce — that can bring the whole community together to restore this symbol that has kind of watched over us for so long,” he said.

He said donations, marked “Indian restoration,” may be sent to the chamber at 23 Commercial St., Skowhegan 04976.

“There are those that appreciate art, and those are the folks that really support the Indian project,” King said. “It does tell the story of our area. It’s a treasure we don’t want to lose.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.