The Bowdoin College Art Museum is featuring a compelling pair of exhibitions about how pictorial modern art came to America.

“Learning to Paint” focuses on American art’s relationship to 19th-century Europe and the development of an American art world. It showcases some fantastic talent: John Sloan, Albert Bierstadt, Maurice Prendergast, Mary Cassatt and Winslow Homer, to name a few.

My favorite part of the show is two portraits hung side by side: one by Munich-educated William Merritt Chase and the other by Paris-educated John Singer Sargent. Chase’s picture exudes bold clarity and sharply honed marks in extreme contrast to Sargent’s liquid-stroked virtuosity in rendering soft light (rather than bare skin or base material).

The bridge between the two shows is Winslow Homer’s painting of fountains at the 1892 Columbian World’s Exposition in Chicago. Homer tips his hat to the Old World: classical sculpture in elegant fountains fronted by a gondola held in relief by the well-lighted gushers at night. It looks like the Old World but tastes like the new, with electric lights and America as an international presence, painted in a style intended to dispel (or at least ignore) the patriarchal fetters of European cultural dominance.

Homer might be adored here for his strong Maine connection, but he was then seen by critics as utterly unrefined — even “bald and crude,” as Bowdoin professor Linda Docherty notes in her essay for “Learning to Paint” in the forthcoming (next month) catalog for this pair of exhibitions.

Docherty’s essay presents a clear and insightful introduction to the education of American artists and the birth of a distinctly American art. She cites the intellectual endeavor undertaken by the entire arts community, including the call for American art criticism offering (quoting Scribner’s Monthly from 1879) “sound principles of art, which will enable us to form judgments and understand” the work of contemporary painters. Critics were being called to educate the public and challenge the painters’ “language” of art.

The main catalog essay is by Diane Tuite, who curated “Methods for Modernism.” While I don’t agree with many of her positions or conclusions, this is the most interesting and instructive exhibition catalog I have read in several years: It is a must read — especially for artists and students of art.

Tuite pursues the discussion about educating American artists in styles opposed to the Academy and importing European modern art to America.

She privileges the role of photography in constructing an American modern art — not only in her essay, but in the exhibition, “Methods for Modernism,” which is loaded with big names (Matisse, Kandinsky, Picasso, etc.) and great Mainers (William Zorach, Marsden Hartley, John Marin, etc.), but also many great works of art in an extremely handsome show featuring 55 paintings and photographs.

The exhibition revolves around partisan debates about the roles of line (disegno) and color. This is an old topic, but Tuite presses the idea that photography was a huge player in developing modern art in America.

Considering that photographer Alfred Steiglitz’s photo gallery “291” was the leading importer of cutting-edge European modernism and that Camera Work, for example, was a leading intellectual American arts journal, Tuite is on to something.

But she seems to swallow the pro-photography cheerleading without sufficiently considering the role of self-interest on the part of those arguing photography was unquestionably fine art — something the public still hasn’t fully accepted.

“Methods for Modernism” sets a debate with line and photography on one side and color on the other.

Joseph Stella’s “Spring” (1915) is a masterpiece and the clear star of the show. It looks like a stream exploding into a million shards of scintillating color. While it’s easy to argue it’s an abstraction with no recognizable subject, I see it as a wildly blossoming spring defined by color: green.

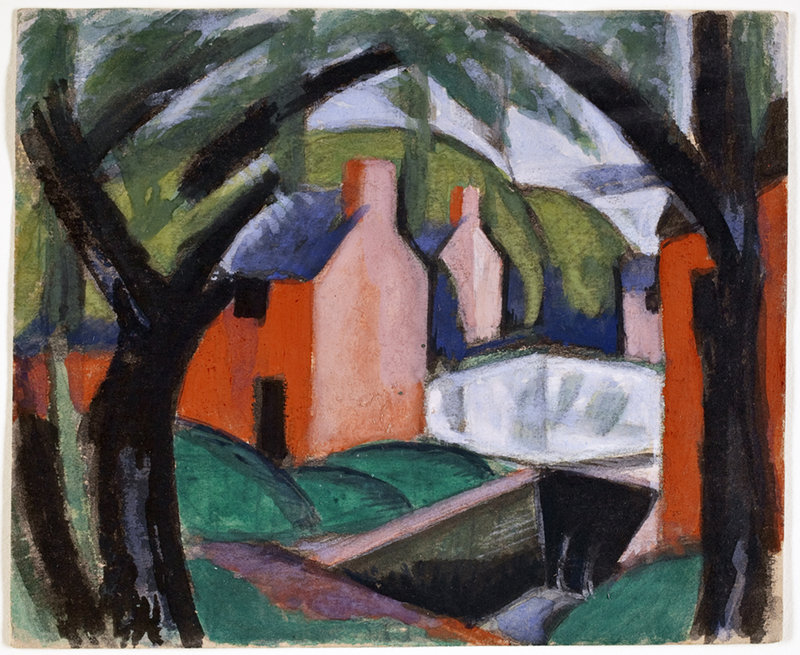

Kandinsky’s “Improvisation #7” (1910) is a similarly gorgeous, color-based painting. Yet, Oscar Bluemner (whose landscape with trees is one of the delights of the show) dismissed Kandinsky as a mere “theorist” and denounced his paintings as “not art — just arrangements of sensitive whims.”

Most works in the show side with the line/disegno camp: photos by Steichen, Weston, Strand and Sheeler; small cubist works by Picasso, Max Weber and Bluemner; even the great colorist Matisse (the belly curve of his figure alone makes this show worth seeing).

I think many of these artists were pursuing essentialist paths geared toward purging anything unnecessary from art. Some discarded color and made strong pictures. Others found that color alone made valid paintings.

But either mode could succeed. As long as the picture was legible, it worked.

At that moment, some artists (including Kandinsky) realized a painting did not need any recognizable object. It only had to be legible as a painting — thus abstraction was born.

This radical break, among others (such as the open door to photography), disproves the essentialist argument that there is some eternal truth to painting — or any art, for that matter.

I think the conclusion of these shows is that art will be whatever our culture learns to recognize as art.

This means, of course, that art will change as our culture’s values and priorities change — whatever direction or whatever reason.

While the catalog and the interesting quotes on the wall hint that “Methods for Modernism” is a heady show, it is nonetheless a gorgeous opportunity for visual indulgence. Whether you want to be intellectually challenged or simply enjoy some great art, these shows would be well worth your while.

Freelance writer Daniel Kany is an art historian who lives in Cumberland. He can be contacted at:

dankany@gmail.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.