Two interesting and strong Wyeth exhibitions recently opened at the Farnsworth Art Museum.

“The Wyeths’ Wyeths” is a show of works from the personal collections of members of the family — most have never been shown at the Farnsworth and several have never been shown in public. While the works of N.C. and Jamie dominate the very few by Andrew, the Wyeth Center is geared to focus on these two — with the main museum keeping a strong thumb on Andrew’s work.

While I am much more interested in art than artists, it’s impossible not to consider the generational differences among grandfather (N.C., 1882-1945), father (Andrew, 1917-2009) and son (Jamie, b. 1946). Instead of considering biography and family, however, I prefer seeing them as successive generations of American artists fully spanning the 20th century.

N.C. was known in his time as the foremost American illustrator. age 21, he had done a cover for the Saturday Evening Post and was dedicated to pursuing art that was genuinely American — probably inspiring the American Regionalists, like Grant Wood, who in turn were major inspirations for Andrew.

In 1922, N.C. was commissioned to illustrate a new edition of Brander Matthews’ “Poems of American Patriotism” — a sort of history of America by its poets. N.C.’s working method was to produce finished paintings (about 40 by 30 inches) to be photographed. To his great delight, a man named Michael Sweeney purchased the entire suite of 17 paintings and donated them to Pennsylvania’s Hill School. Sixteen of these works survive. As a group they make for a terrific show.

In “Poems of American Patriotism,” we see N.C.’s illustrations of American literary landmarks such as Walt Whitman’s ode to Lincoln, “O Captain! My Captain!” While the vast majority of N.C.’s pictures feature compositions typical of strong painting, a few assume the sensibility of graphic design. The title page illustration, for example, features Washington on horseback riding with a column of troops: Looming behind them is a dreamlike image of the Statue of Liberty. It sounds heavy-handed, but it’s a strong graphic that conveys memory and the process of American myth-making.

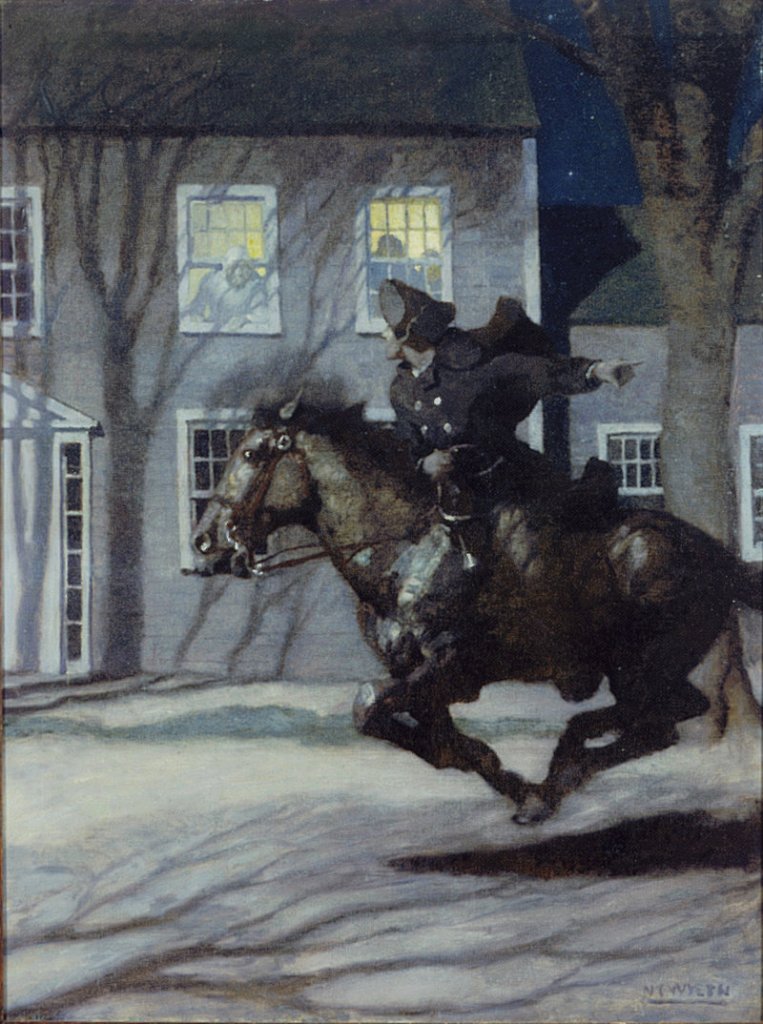

I adore the companion painting to Longfellow’s “Paul Revere’s Ride”: Through the shadows of the steely moonlight, Revere (a propaganda artist himself) calls men in a farmhouse to arms as he spurs on his galloping horse. From two (gorgeously impastoed and) yellow-lighted windows, faces look to the fleeting Revere as he gestures back towards the British onslaught.

History paintings topped the European hierarchy of genres 150 years ago — and the illustration work of N.C. was done with all of the historical rigor, narrative sophistication and painterly refinement as the masters of the Parisian Salon. N.C. was a cultural star in America — a very successful and influential artist.

The most interesting contrast is between a pair of images by Jamie in “The Wyeths’ Wyeths” and N.C.’s work from “Poems.” Jamie’s first study for a picture to commemorate 9/11 shows four figures assuming the famous pose of the flag-raising on Iwo Jima — including a fireman and a policeman. It seems agonizingly cheesy, but, in fairness, it’s an early study.

Another image is a study for “Night Vision” — a painting made into a print to benefit the Vietnam Veterans’ Memorial in Washington. With our nation divided by a pair of controversial wars, these might appear (unfairly?) to some viewers as jingoistic baubles rather than persuasive salutes to national service.

Ironically, the last time N.C.’s “Poems” were shown at the Farnsworth was in 2001 (how different they must have seemed then). As fodder for meditating on the ideas of patriotism, propaganda, history, memory and myth, these really are great shows.

The somewhat absent fulcrum in this equation is Andrew. N.C. appears as a rigorous and far-ranging artist (his large, Cezannesque still life is exquisite). We see Jamie as a great talent who can walk in the footprints of his forebears or, typical of a contemporary artist, follow any whim in any direction. Andrew, however, was a great American painter of singular and solitary vision.

I happen to prefer N.C.’s brushwork, but Andrew was one of America’s great technical masters. He distilled mystical still lifes from anything — whether landscapes, people or objects. A shell on a windowsill becomes a reminder that a person — now gone — sat there and meditated on it. Every object becomes both a memory trace and a marker of mystery. A sleeping woman seems to be dreaming — but about what? The painting reminds us she is gone and is now just a memory. Or was the image drawn from memory rather than her actual physical presence?

Andrew’s “Dance of Death” features a masked and hatted scarecrow in windswept cloak — uncannily terrifying. The end-season air is cold, and the gray-light landscape is at the tips of winter death. His vision is a dream slipping uncontrollably on the icy edge of nightmare.

Instead of bowing to the ironic play of Postmodernism, Andrew never left the mystical individualism of American transcendentalism. For this, he has been criticized and at times pressed out of fashion by art-world hipsters. However, the meditative spirituality of Andrew’s art refused to die when he did, and I suspect it never will.

“The Wyeths’ Wyeths” features a suite of watercolors by Andrew when he was 12 years old. It shows N.C. as a great artist. It shows Jamie’s vast range and abilities. And it shows that it’s wrong to see the Wyeths as a monolithic or hermetic presence — for they have been great artists of our culture, and our culture has never stopped changing.

Freelance writer Daniel Kany is an art historian who lives in Cumberland. He can be contacted at:

dankany@gmail.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.