“Vernal Pools” at the Atrium Art Gallery at Lewiston-Auburn College is the primavera of the spring season. I offer such redundancy as an affectionate bow to an exhibition that softly stirs the biologic soup of spring. Vernal pools — more saucers than bowls — appear almost as much from memory as in fact, stay around for a few weeks and then abruptly vanish. Some are called back by wet autumns, but without the slippery green concoctions of spring. Their reappearance lacks expectancy.

“Vernal Pools” is about those green concoctions. It treats of skunk cabbage, water striders, dragonflies, fairy shrimp and choice frogs, salamanders, turtles and snakes. It is an advocate for small temporary universes that in time give up their products to benefit larger and more stable ecologic enterprises. The seasonal pools are destined to supply the uplands and wetlands with small creatures to grace their enterprises.

All of this is suggested in the work of 16 artists selected by the gallery. Drawn from around New England, they inquire into the natural history of our spring through a variety of media including poetry. The work closely follows the theme of the event and none of it has the aroma of haste that often accompanies theme shows. Produced-for-the-event efforts seldom represent the best work of the artist and, by the same token, seldom really fit the prescription of the event. In this show the work was already in existence and was selected because of its aesthetic and ecologic inclination toward a public discussion about vernal pools.

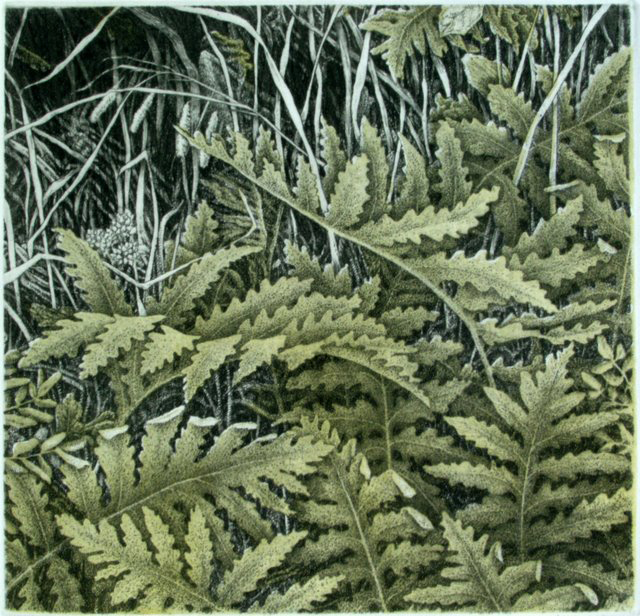

In a show so select, excising a few works to talk about is an almost arbitrary act, but some in it urge my thoughts more than others. I begin with Barbara Putnam’s “Skunk Cabbage” and “At the Water’s Edge.” Each a woodcut, each printed in black and white and each exceptionally large, they are magnificent accomplishments. As narratives about the landscape, I would be hard-pressed to cite their equal in the medium. I must confess to an initial reservation about “Skunk Cabbage.” Vernal pools are seductive, in part, because of their transiency. They don’t linger. They have to seize the moment and this implies vulnerability. Putnam’s print, however, is almost thunderous in its power. It presents a jungle of indestructible botanic forms that succeed one another into infinity. Space in it has no edge. I have come to understand this as a metaphor for the continuous seasonal return of the slippery slime of the pools and the life incubated within them.

“At the Water’s Edge” is more specifically aquatic and has a more spontaneous two-dimensional and calligraphic quality that I associate with Japanese aesthetics. It is a delicate achievement for so large a work.

Kristin Malin’s “Early June (Vernal Pool 4)” is a small oil on panel. It, and others in a series by this artist, look at pools as landscapes unto themselves. They are not extractions from the pools of exotic forms or of particular biologic incidents; they are just there, sitting in space as nature made them. They smell of the expectancy of early spring after having extracted enough sun to give them an advantage over their more self-assured forested neighbors. When viewing this painting, read Malin’s wall statement. It is moving in its tenderness and affection.

“Wetland — Late Summer,” a two-plate etching and aquatint by J. Ann Eldridge, reminds me that not every wetland dries up by June. In its depth it holds the earlier plant forms while making space for the later botanic growth. It is superb in its complex layering and in its elegance. I also note Rebecca Goodale’s collages superintended by representations of birds that have snared dragonflies or what appear to be spring butterflies. They are charming in their folkish directness. The birds may be quiet, but they are not posing.

THE ARTFUL FURNITURE MAKER

If you are drawn to furniture infused by tradition and made with notable excellence, there is a rare opportunity at hand. Kevin Rodel’s studio in Brunswick will be open to the public through early June. Rodel is a custom furniture maker and, like others of the ilk, seldom has work to show. Things get made and go out, leaving only photographs behind. As chance has it, he has a group waiting to leave and because his work is singular in Maine, the occasion is worthy of note.

If Maine has a current furniture-maker attitude, it runs from Shaker to Modernism as interpreted in wood. I note that there are also references to formal and provincial forms extracted from the 18th century, but by and large the simplified forms from the range I have suggested prevail. Hence my suggestion that you see Rodel’s work. It is outside of the present range. He works within the attitude of, as he puts it, International Arts and Crafts. His furniture provides an opportunity to roll Charles Rennie Mackintosh, Vienna Secession, Wiener Werkstatten, Joseph Hoffman, Kolomon Moser, Eliel Saarinen, Frank Lloyd Wright if you wish, Harvey Ellis, Stickley, Greene and Greene and Japanese Arts and Crafts around in your mind. Those designers didn’t quite fuse, but they kept an obvious eye on one another.

Rodel’s work is not a distillate of that brew, but its deep bows to Mackintosh and lesser nods to the old Japanese Arts and Crafts movement fascinate me. There is a wistfulness to Mackintosh’s work that finds its way into Rodel’s. Mackintosh flourished from the 1890s through the early 1920s in Scotland and Vienna, but the richness of the period for designers did not fully embrace Mackintosh.

There is an underlying severity to his work — his manner of manipulating mass, space, line and color — that is fascinating. It invites you to inspect, but then insists that you accept it for its rationality despite the lure of its decorative elements. Of the latter, the decoration — geometry and reduction to essential organic form — is ravishing if I can apply that term to almost dictatorial underlying forms. I find this fascination in Rodel’s beautiful furniture.

If you don’t get all this, take the opportunity to look at the work now at Rodel’s studio. It’s a pleasure to see. There has been no comparable opportunity in a public space.

Philip Isaacson of Lewiston has been writing about the arts for the Maine Sunday Telegram for 45 years. He can be contacted at: pmisaacson@isaacsonraymond.comI

Send questions/comments to the editors.