Sarah Hesselink loves food, and she loves writing.

So when the 14-year-old from King Middle School was given the assignment to write about food, she couldn’t wait to get started. She knew almost immediately what her subject would be: latkes.

“They’re one of my favorite foods,” Hesselink said, “and they also kind of say a lot about my family. And they really do tell a story.”

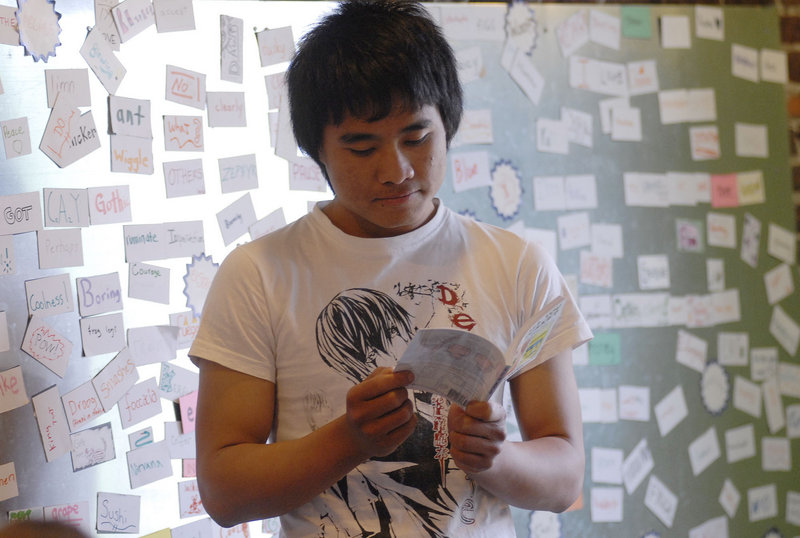

Sarah is one of 35 budding Maine food writers who have just published a collection of their stories and poems about food in a new anthology, “Can I Call You Cheesecake?” It’s the culmination of a year’s worth of workshops and mentoring by the staff and volunteers of the Telling Room on Commercial Street, a nonprofit writing center where children and young adults learn how to tell their own stories.

The anthology is not just another collection of reminiscences about lobsters and whoopie pies.

“When I was 9, I wished I could be a carrot,” writes Christina Murray, who attends Catherine McAuley High School. “I could’ve disappeared behind a cliff of meatloaf or under a river of gravy at the dinner table.”

Some of the students whose stories made it into the book were born in Maine, but others hail from India, Iraq, Somalia, the Dominican Republic, Burma, Uganda and Sudan.

Agustin Nyapir, a native of Sudan who attends Casco Bay High School, wrote a lovely and humorous account of trying to make aseeda, a Sudanese porridge, one day when his mother left him home alone and he got hungry: “Aseeda looks white because of the flour it is made with, and it is as pale as the sky, the color of the first day of snow. It tastes like freshly baked bread. It feels soft enough to sleep in while you dream.”

The students write about everything from the thrill of a Berry Backlash slushie to life from the point of view of a spoon. One or two of the stories includes a recipe.

Gibson Fay-LeBlanc, executive director of the Telling Room, says the staff has always used food as a way to get students interested in writing. With this project, they wanted to expand food’s role in the group’s workshops because “it’s just a great window into family and culture and geography.”

Often, the staff will bring out different foods for the students to taste and smell, hoping that a jar of olives or a whiff of stinky cheese will unleash their creativity. The students hold unnamed spices under their noses and linger on the scent of sage or mint or cumin, “and let that carry them somewhere,” Fay-LeBlanc said.

“What does this remind you of? So often, smell, in particular, just goes right back to memory, so in terms of writing personal stuff, that’s a great starting point.”

An olive, wrote Janet Mathieson of the Middlesex School in Massachusetts, “tastes like the bottom of a pond.”

Many of the pieces start off being about food, then turn into very personal accounts of life and family. Some of the stories are warm; some are heartbreaking.

Writing her story about her mother’s latkes sizzling in hot oil helped Hesselink learn more about her grandmother.

“I didn’t know her very much when she passed away because I was only 2 or 3,” she said, “so it was really cool to learn about her and about how she was when she was younger.”

Lee Reh, a 20-year-old student at Portland High School, teamed up with his brother, Ti, to write about rattan in their native Burma.

“It has no smell but the fruit of the rattan tastes sour and good,” they wrote. “Our father risked his life to get it for us.”

writing about rattan, Reh and his brother ended up learning more about their family’s journey from Burma to a refugee camp in Thailand and then to America.

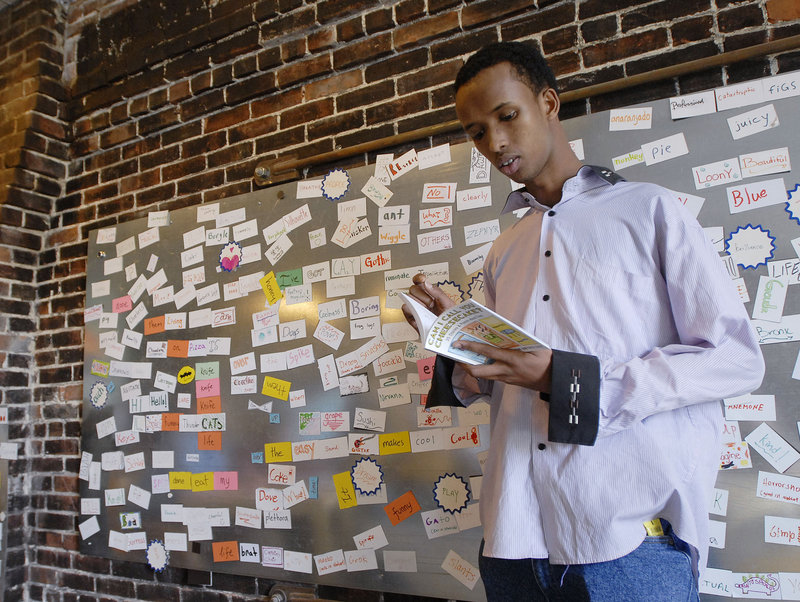

Rabiic Gedi, a 17-year-old from Portland High School, wrote about his mother’s lemon stew and how she taught him to make rice with lemon. Over the course of three weeks, Gedi interviewed his mother about lemons in Somalia, and learned that in the United States, lemons grow in Arizona and California. He drew pictures of lemon trees.

Gedi’s ode to lemons eventually segues to the story of how his father was killed by a stray bullet from street fighting while working in a shop in Mogadishu.

After his father’s death, his family moved to a refugee camp in Kenya, where they ate lemons every day.

“When I sit with my family at the table, I need to forget that there has been a war in our country for 20 years, longer than my whole life,” Gedi writes. “It is easier to forget about my father than be sad, but the smell of my mother’s stew reminds me.”

Staff Writer Meredith Goad can be contacted at 791-6332 or at: mgoad@pressherald.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.