Even if you have never heard of Carlo Pittore, you have probably felt echoes of his activities in Maine. For example, he founded the Union of Maine Visual Artists, which helped establish Maine’s Percent for Art program and craft the first legislation in America allowing estates of deceased artists to help pay tax debts with works of art.

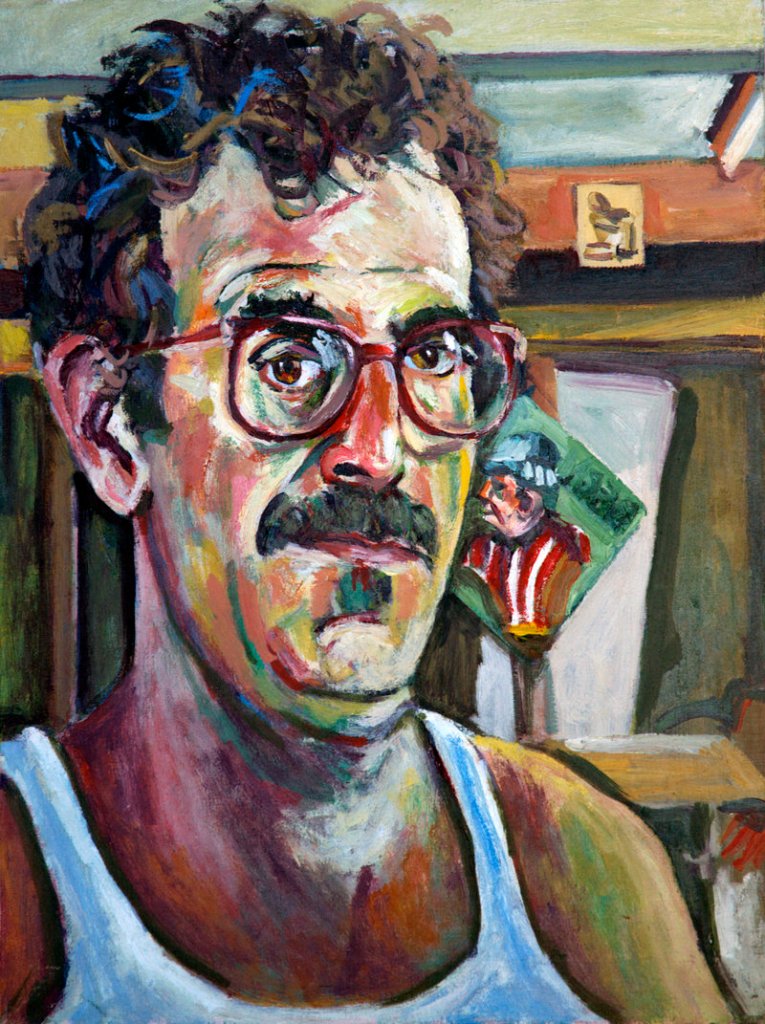

While he was an artist advocate, educator, publisher, actor, filmmaker and performance artist, Pittore was fundamentally dedicated to painting. His works are figurative and largely inclined to portraiture.

Pittore studied under Joan Semmel and Alice Neel, and I think it’s fair for a thumbnail description to say his work falls between Semmel’s unblinkingly odd eroticism and Neel’s organically empathetic portraiture.

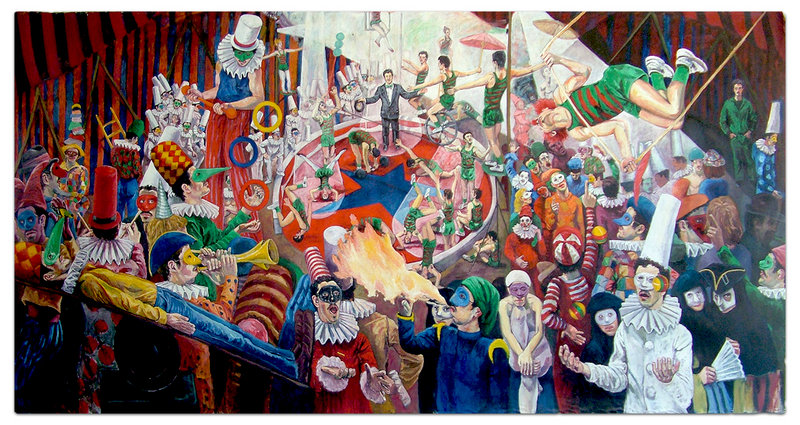

“Carlo Pittore @ The Constellation Gallery” features 33 works that showcase Pittore’s range, skill and painterly ambition. The show revolves around an enormous (8- by 17-foot) canvas shown for the first time since it was painted in 1983. “La Buffonera” (“the buffoonery”) features dozens of wildly energized performers in and around a circus ring.

In the center quietly stands a calm figure with his arms outstretched to present the entire performance. His gaze is fixed directly on you. He looks familiar — because he is almost every one of the 100 or so performers. (Pittore loved painting boxers, and this man was one of his boxer models.)

Despite the cacophony, “La Buffonera” is an extremely well-composed and structured painting that immediately brings to mind James Ensor’s similarly-sized 1888 masterpiece, “The Entry of Christ into Brussels.” Ensor’s carnivalesque and creepy characters form a crazy parade in which Christ is humbly mounted on a tiny donkey and quietly centered like Pittore’s ringmaster. But Christ seems to be forgotten at the party in his name: Not a single eye falls upon him.

I have no doubt Ensor’s painting was the main inspiration for “La Buffonera,” but Pittore takes his work in a completely different direction than the cynically misanthropic Ensor by exuding an optimistic enthusiasm for people and culture and a palpable love of humanity. Ironically, it might be his sympathy for all mankind that drove his admiration of outcast artists such as Ensor, Goya and Pietro Longhi (an 18th-century Venetian whose paintings are echoed by masked figures in the lower right).

“La Buffonera” is a recent discovery, so there is no definitive interpretation of it. That alone makes this an incredibly exciting exhibition.

I think the key is Pittore’s deep connection to the theatrics of portraiture and his obsession with painting self-portraits. In this show there are at least seven, including self-portraits as a weightlifter, a drummer with mouth opened in song, a wizard and a spectator of a chaotic performance in a 1978 painting titled “The Rag and Bone Shop” that sets the stage for “La Buffonera.”

“The Rag and Bone Shop” is from the last line of William Butler Yeats’ “The Circus Animal’s Desertion,” which, the poet said, was about his thoughts on Christianity. To conclude the poem, Yeats insists the author “lie down where all ladders start.” Yeats’ point is that any ending marks a new beginning.

We see a performer by a ladder looking toward its obscured base with the literal form of a man lying below it in the foreground (on a ladder?) in the lower left — where Pittore painted himself in the earlier work. In the later painting, however, Pittore shows himself quietly exiting to the right (the end of a page in Western culture). The two paintings share much in terms of structure and theme, including a specific form of a trapeze artist in the upper right; their interconnected narrative is undeniable.

Ensor’s and Yeats’ meditations on religion and Pittore’s recycled forms make for a clear start for interpreting the huge painting. Yet Pittore’s use of a single model for most of the figures (many of whom are recognizable despite being masked) hints that this picture is a single portrait of the many roles, identities and episodes that make up an individual. If a boxer, then he is the sum of all his fights. If an artist, then he is the sum of his entire oeuvre, and so on.

Pittore could really handle a brush, and this shows in his oil paintings as well as his studies and sketches. Pittore’s portraits of friends — as Mao or a clown or a sculpture — are quirky and deliciously painted.

There are luscious watercolor sketches for “La Buffonera” and related drawings of clowns from Italian comedic opera. Pittore’s black line brush drawings show off his spontaneous wit: Two feature a man riding backward on a donkey (remember the Ensor), and one shows a baseball umpire/Yankee/clown hilariously placing a lighted firecracker on the backside of an unsuspecting catcher.

It is not often that you get to see recently discovered paintings by major artists as complex and strong as “La Buffonera.” Coupled with 32 other works, this makes for a fascinating portrait of a late, great Maine artist.

Freelance writer Daniel Kany is an art historian who lives in Cumberland. He can be contacted at:

dankany@gmail.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.