BRUNSWICK – Blood in a test tube is not that scary.

Neither is urine, for that matter.

When I arranged to spend some time in the lab at Mid Coast Hospital, the idea of working with blood and urine, or any kind of body fluid that wasn’t my own, made me a little nervous.

But when I got to the lab, the various samples ready for testing were all neatly secured in packaging that made them much less imposing. Blood was in test tubes or plastic bags, and looked more like some red food coloring concoction to me. Urine was in test tubes to be handled with rubber gloves and a dropper.

Still, I was slightly nervous when Kate Cote, the medical laboratory technician with whom I was working, asked me to dip a dropper into a tube of urine and drop it onto chemically treated paper to see how it reacted. The reaction, Cote said, would tell us if the person the urine came from was pregnant.

I thought everybody did pregnancy tests at home.

“The doctor still needs to make sure,” said Cote, 33, of Lisbon. “And sometimes, a person might come into the ER unconscious or incoherent, and doctors will need to know everything that’s going on with that person, any conditions before treating them.”

That includes pregnancy.

Cote also showed me some urine that was red because it had red blood cells in it. Probably a urinary tract infection, she said.

Then, as Cote was listing all the things that testing urine and blood cells can help determine, she mentioned that in the very early days of hospital laboratory science, lab technicians checked for diabetes by tasting urine.

“Way before any of us,” she said, “maybe 75 years ago.”

Well, that’s a relief.

CHEMISTRY-KIT TYPE OF KID

Cote said she had considered going into nursing but decided that dealing with some of the messier, up-close-and-personal aspects of health care was not for her. She was always a chemistry-kit type of kid who loved looking at things under microscopes and testing organic matter in an effort to find health care problems. Still does.

And she’s still helping sick people. In a big way.

As a rule, 70 percent of all diagnostic decisions are based on lab results, hospital officials told me.

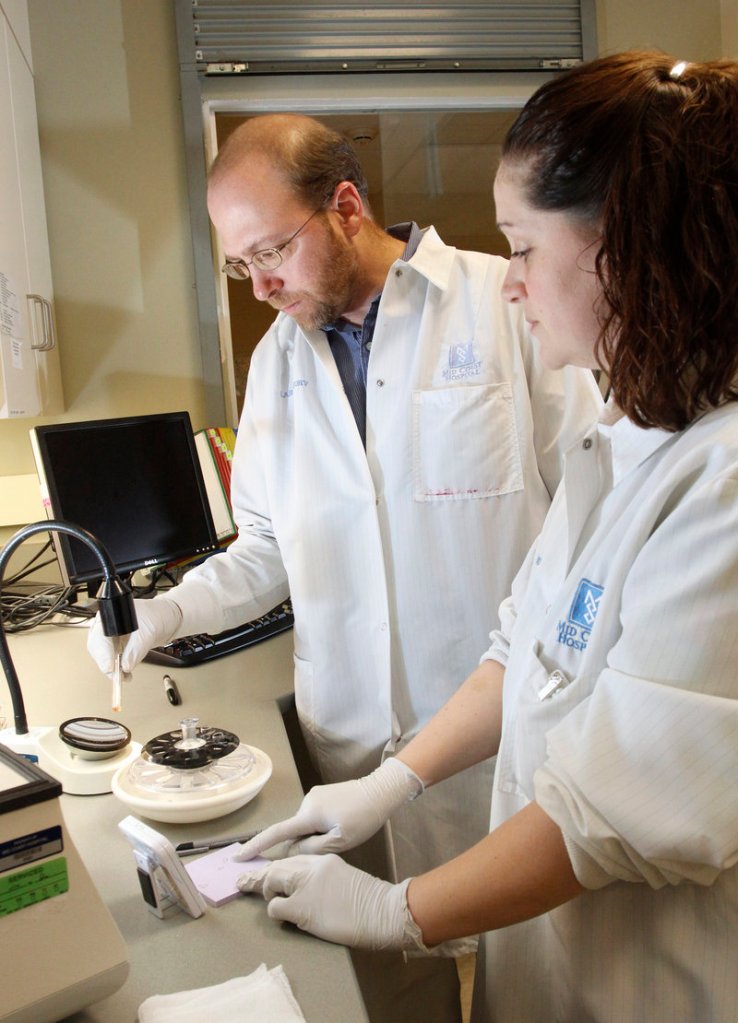

“We can do so many tests here that help the nurses and doctors figure out what to do or if treatment is working,” said Cote, who became an MLT after completing a two-year program at Central Maine Community College in Auburn. There is also a four-year degree for lab workers, and the position is usually labeled as a “medical laboratory technologist.”

Part of Cote’s training included conducting lab work 40 hours a week for a year. The lab technicians have to understand what they’re looking for, and why it matters, in every blood cell or tissue sample they test.

About 30 people were working in the lab in various areas when I was there. The lab processes about 600 test tubes and 100 or more cultures a day, performing thousands of tests.

Some were working in the blood bank, matching donated blood to patients. Some were in the microbiology room, growing bacteria samples obtained from patients to better identify them for treatment. Others were looking at blood cells under microscopes or running blood cells through a machine that counts them.

At one point, Cote had me look at urine samples under a microscope that magnified the cells to 40 times their size. To me, it looked like a bunch of purplish-blue circles and squiggles. But to Cote’s trained eye, the lines and squiggles were very specific, and important, components — red blood cells, white blood cells, crystals, bacteria.

KEPT IN THE DARK

The test was ordered by a doctor to see if treatment on a patient was effective. Cote said the lab technicians don’t know exactly what the doctors are looking for, or what the patient’s condition is. That way, they don’t have information that might skew their recording of the test results.

Over in the blood bank, we took test tubes and created suspensions of blood cells separated from plasma to look for antibodies and other matter.

Again, the science was way over my head, but basically Cote told me we needed to make sure there was nothing in a patient’s blood, or in the donated blood, that would indicate the two could not be matched. You don’t want to give a patient blood that will make them sick.

At the blood cell counter, we tested some samples that had a white cell count of 187. That’s probably an indication of leukemia, Cote said.

Besides microscopes and lots of test tubes, the lab was filled with machines that do many of the actual tests on blood, urine or tissue. Many looked like giant copiers or printers, with a small compartment to put the sample in.

Cote told me that, just like with copiers, if the testing machines break down, it’s often up to the lab technicians to try to fix them. Sometimes it means they have to get on the phone with the manufacturer to get to the root of the problem.

Although the lab technicians work mostly in the lab (naturally), they sometimes go to patients’ rooms to draw samples as well.

Sometimes, Cote draws blood from a patient every day — until one day, they’re not there.

“It’s hard,” Cote said. “You get a connection to people.”

Staff Writer Ray Routhier can be contacted at 791-6454 or at:

rrouthier@pressherald.com.

Send questions/comments to the editors.