CORRECTION:

PHOTO CREDITS ON THIS STORY HAVE BEEN EDITED TO REFLECT THE PROPER PHOTOGRAPHER.

There is a felicity to the Frederick Lynch exhibition at the Portland Museum of Art that I did not anticipate.

That quality fosters a sense of good fortune in just being there. I attribute this heightened state to the work on view to what I know of the development of Lynch’s art to the installation and to the skylit gallery itself.

First, the gallery. It is Henry Cobb’s deep bow to Sir John Soane’s idiosyncratic Picture Gallery at Dulwich. Situated in one of London’s farthest reaches, the 1811 top-lit Picture Gallery is Soane’s personal abstraction from forms that were fashionable in his time. Dulwich has skylights that appear to have detached themselves from its walls and hover as planes and sharply angled divisions of space.

Cobb borrowed those skylights for his PMA; however, much of his yearnings for the eccentricities of Soane are lost in his wonderful building. Dulwich is low and modest. PMA is neither. The skylights embraced by Cobb are largely obscure in the distance, except (and here I’m getting to the point) in the building’s hushed fourth-level gallery. There, Soane, Cobb and Lynch meet in a joint adventure that fills me with joy.

There is a correspondence between the noted British eccentric, the connoisseurship of Mr. Cobb and the accomplishments of Mr. Lynch that is thrilling. It is a conjunction all the more precious for its rarity. To this, as an accent, I add the clarity and the meticulously considered installation by Sage Lewis. It too is a presence.

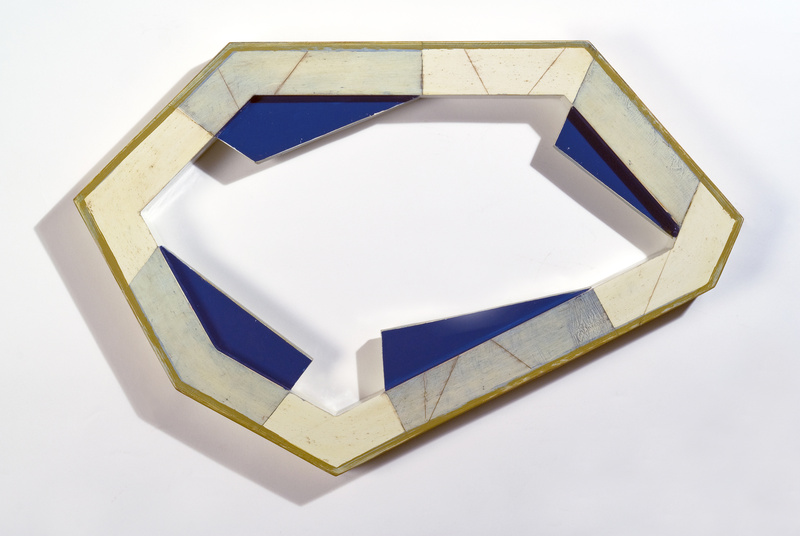

And now to Mr. Lynch. The emphasis in this show – which, by the way, is called “Division and Discovery: Recent Work by Frederick Lynch” – is on how the work comes into being; what, in a visual sense, generates its forms.

My own interests are somewhat different. Lynch is our pre-eminent abstract artist. He and a handful of others whose work I know and admire exist in a microclimate of their own local making. Their burden is to deflect our minds from the rules of traditional vision-based perspective and to encourage us to focus on the descriptions that make up geometry. Doing so encourages thoughts about the logic and clarity found in science and technology.

With that focus – the study of descriptive geometry – my interests come into play. I find in the prescience of Soane and its admiration by Cobb a romantic affiliation with geometry, and that is a bequest that enhances the display of Lynch’s work. And that work plays to it.

Does that imply a romantic response on the part of Lynch? The answer is yes, particularly in connection with his more recent work. Over the years, Lynch has allowed himself subtle excursions from the predictions of geometry. You would see this in his voluptuous handling of paint and in various linear temptations. Whether there is romance in this is open to argument – whether it fits with my view of the eccentricities of Soane as embraced by Cobb – but I think his current work advances my position.

To understand this, you have to see the show; reading the cogent artist’s statement in the handsome brochure would be of help. Briefly, Lynch explains that he is involved in applying geometric systems that produce constantly changing and unexpected results. The operative word here is “unexpected,” and therein lies the romantic component. In these departures from the rational, there is a fellowship with Cobb’s excursions, and whatever forces brought Sir John Soane’s aesthetics into being. Although all three appear neat and tight, the expressionistic urge is not that far below the surface in any of them.

One final thought about Frederick Lynch. The work in this show embraces a number of media – oil, ink, gouache, wood – and range from painting and drawing to relief sculpture. It is a big show, and the work was accomplished in a few years’ time. The work is not a restatement of what the artist has been doing throughout his career, a span that has been marked by an unbroken flow of innovative convictions offered in remarkable volume. This show is another elevating chapter in that flow.

In this and in every other respect, Lynch is an inspirational artist.

FINDING THE AFRICAN EDGE

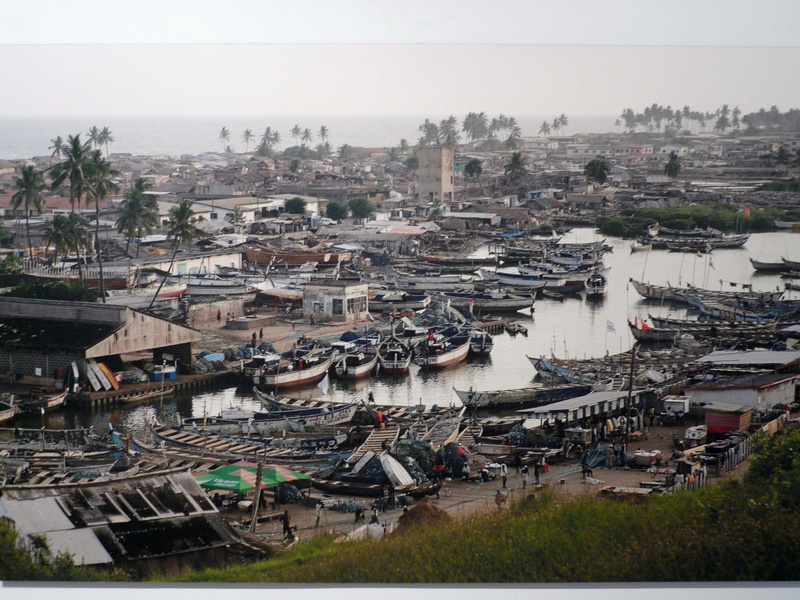

For a warm, ebullient show, I recommend “Ghana: An African Portrait Revisited” at Edward T. Pollack Fine Arts, presented in collaboration with the Addison Woolley Gallery.

Largely color photography, it represents work by six New Hampshire photographers who went to Ghana in 2006, spurred by the 50th anniversary of its independence. The “Revisited” in the title acknowledges a visit to Ghana by the noted photographer Paul Strand in 1963.

In 42 images, these photographers pick and choose their way among the people and landscape of that richly embroidered nation. There is no evident visual tribute to Strand.

It is a given that photographs of any West African nation are going to be exotic and interesting. The colors, the situations, the fabric of the land have a visual pulse that engulfs the viewer. The challenge to the photographer is to transcend the obvious and the curious to produce images that have edge. Charm when charm is so attendant is not adequate. The artist has to push to another level and find things intrinsic to the subject. To attain this implies long residence and slowly achieved contact.

I don’t know what the circumstances surrounding the making of the images were, but assuming the contact was a visit and not a prolonged residence, the results are of a high order.

Some prints are graphic and bold as one would anticipate; others are memorable of their genre. The best involved the relationship between people and industry, packed life along the edges of a great river, and a fetching image by Nancy Grace Horton of a young girl near a wall embellished by a clothesline.

AN INVITATION TO MEDITATE

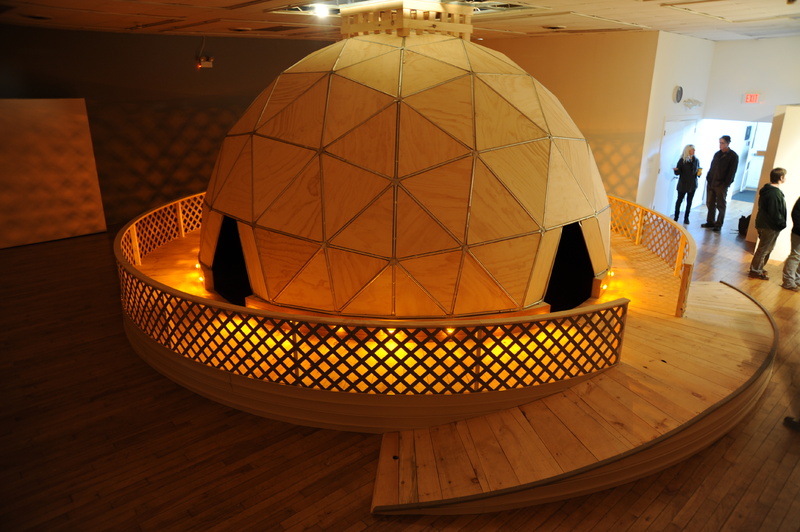

Finally, I mention STUPA Duplicator at the Art Gallery, USM Gorham. I was drawn to the event by the name. I’m something of a stupa addict, having climbed a number of the domed monuments in a number of places. Some were big, and some climbs were barefoot. All indigenous stupas are intended to commemorate significant Buddhist teachers by housing their relics.

In this instance, the stupa is a handsomely achieved structure that largely absorbs the entire gallery. It is based on the principle of a Buckminster Fuller geodesic dome, and it is not difficult to think of it as representing an enlightened mind. You can extend that to think of it in relation to the heavenly dome of the eternal.

It can be entered, and thus easily invites meditation. I suggest that as impetus for a visit.

Philip Isaacson of Lewiston has been writing about the arts for the Maine Sunday Telegram for 44 years. He can be contacted at:

pmisaacson@isaacsonraymond.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.