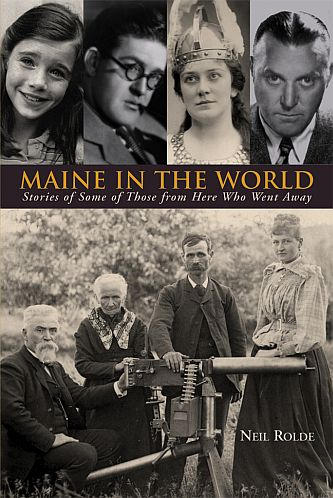

Maine has a special capacity – out of all proportion to its size – to lead by example. We tend to think of this dynamic in communal or civic terms, but in his latest book Neil Rolde ratchets it up to the plane of individual destiny. “Maine in the World” celebrates the deeds of a couple of dozen Maine-bred men and women whose circumstances for one reason or another sent them out into the world.

Whether collecting poems or people, the anthologist will always be called to task for what or who he left out. Doubtless Rolde is even now placating those whose heroes or heroines he ignored. The good news, of course, is that these conversations are certain to provide material for another book.

History as a mosaic of personal stories is fascinating, especially when they interconnect as much as they do here. Rolde presents his characters in chronological order, attending to their origins as well as their exploits, and the result is a lively portrait of our state. Clearly this was one of his criteria in choosing his dramatis personae.

Another was finding an appropriate mix of known and unknown faces. Henry Wadsworth Longfellow rubs shoulders with one Asa Meade Simpson of Brunswick, whom the author stumbled upon visiting a state park in Oregon. According to an informational panel there, Simpson made a North Western timber empire that “built homes and buildings on at least four continents.”

In “Maine in the World,” the various reasons to seek a life “away” boil down to four principle motives. Some found themselves at the behest of an external agency. Most dramatic – and involuntary – is the case of five Indians kidnapped and brought to England by Captain George Waymouth in 1605. Others were sent abroad by their country, like the dashing Commodore Preble quelling the Barbary pirates, or a pair of nineteenth century diplomats, one the first ambassadors to Mexico (though for less than a year) and the other ambassador to The Hague (which he didn’t seem to enjoy very much).

While most of Rolde’s subjects, with the exception of Waymouth’s Indians, left the Pine Tree State to better themselves in some way, material self-interest played a particularly dominant role in the cases of William Phips and Samuel Waldo, crisscrossing the Atlantic in pursuit of their personal, political and commercial affairs. Likewise, the aforementioned Simpson sought his fortune on the Pacific coast. And there is the Joker in the deck: Sir Harry Oakes, the biggest rogue of all, who ended up murdered in the Bahamas.

A trio of artists found the world clamoring for their talents. Longfellow’s initial exposure to Europe prepared him for teaching at Bowdoin and then Harvard, but he returned several times as a literary lion. Lillian Nordica became the first American to sing at Bayreuth, the shrine to Wagner’s music, still run by the composer’s widow. My favorite is the stand-up comic who performed under the name of Artemus Ward. Apparently, his writings were a favorite of Abraham Lincoln, who read a chapter to his bemused Cabinet before announcing his intention to issue the Emancipation Proclamation.

Finally, there are those who left the world a different place, or tried to, for good or ill. The most ambiguous, I suppose, is Sir Hiram Maxim who invented the machine gun. On the pastoral side, the figure whose story inspired “Maine in the World” in the first place was a graduate of the Bangor Theological Seminary and became a missionary on a tiny Pacific Island, Kosrae. So successful was he that over a hundred years since his death, the churches he built there are still standing-room-only on Sundays.

Most touching is 10-year-old Samantha Smith, who, as the world grappled with the potential of “nuclear winter,” took it upon herself to ask the Soviet premier directly, “Why to you want to conquer our country?” Tragically, her life was cut short in an air crash.

Rolde is an excellent raconteur, not afraid to use the vernacular. So we find Waymouth “casually tootling around the Maine coast,” and learn of Phips’s staunch supporter, Cotton Mather, “as a spin doctor, the minister was a master.” Not the least of the book’s fascination comes from the great and famous who appear in cameo roles.

Tilbury House has produced an attractive paperback, although there are a few more typos than there ought to be in this day and age. I can’t resist one quibble: In order to assist his son win a bet involving a two-headed coin, “Sir Hiram (Maxim) created a penny with a Lincoln head on either side.” This presumably took place in the 1870s, but the Lincoln penny was not introduced until 1909, the centenary the Great Emancipator’s birth.

Never mind: This is a great addition to the Maine history shelf, and I look forward to Vol. II. I have no doubt there are still plenty of candidates.

Thomas Urquhart is the former director of Maine Audubon, and author of “For the Beauty of the Earth.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.