Art galleries often match their shows to the exhibitions at nearby museums. From the public standpoint, this can be a great thing: Galleries don’t charge admission, staff members answer questions and many people like seeing work they could actually buy. Conversely, museums and their public audiences are often the ultimate beneficiaries of the activities of local galleries and collectors.

“Modernism and Masquerade” – an exhibition of Max Beckmann prints at the Portland Museum of Art – underscores the strength of the museum’s community.

The show’s 40 works are largely drawn from the PMA’s collections (mostly gifted by David and Eva Bradford), with a few on loan. For being culled from the museum’s own holdings, it is a surprisingly strong show.

Beckmann (1884-1950) is an interesting artist. He is understood as a pivotal figure of German Expressionism even though he distanced himself from that label. Beckmann was respected in his lifetime, but his legacy has continued to grow so that he is now considered one of the giants of Modernist art.

I think Beckmann’s increased critical fortunes are due to the ascendancy of the American focus on art with a heavy dose of “self” in unique self-expression.

He certainly was a tremendous talent and a brilliant man, but he also fits American myths and molds of the recipe for a great artist: Beckmann was classically trained, but his work turned away from that training; his WWI trauma is reflected in his work; he was brilliant but troubled; he struggled at times for money; he was demonized by Hitler; he was critical of bourgeois society; he desperately wanted to come to America; and he was self-absorbed to the point of obsession.

One thing Rembrandt, Van Gogh and Picasso share with Beckmann is the fact they produced so many self-portraits. Self-portraits would seem to be the hardest thing for an artist to sell (especially as prints), yet Beckmann’s are now more valuable than the rest of his graphic oeuvre. (You can check the prices at Susan Maasch Fine Arts, where three of the works from the PMA show are being shown – including two of the seven self-portraits.)

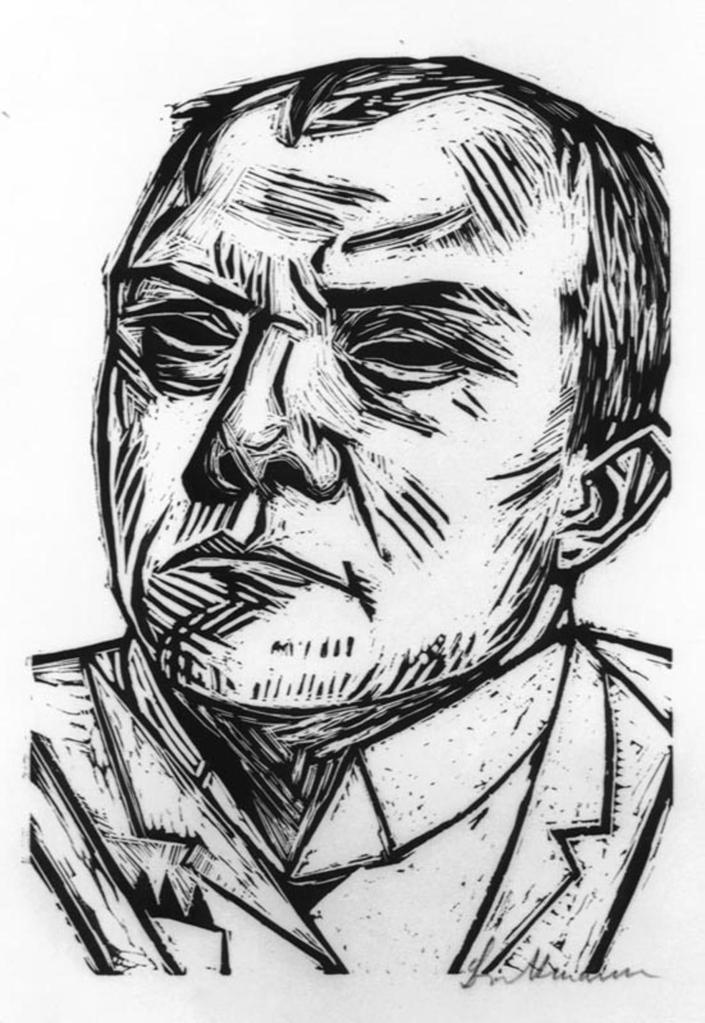

One of the most notable works in “Modernism and Masquerade” (also at Maasch) is a drypoint etching self-portrait of the artist wearing a suit and holding a stylus. Beckmann often made his prints without preliminary sketches, and here he doesn’t hide where he re-worked the plate. These changes reveal his thought processes and insist the print be seen as drawn in real time. It is an exciting metaphor that Beckmann’s hand actually moves. The point of view looks up at the artist – the sign of hubristic arrogance or the simple effect of drawing flat on a table while looking straight into a mirror?

Beckmann’s self-portraits are mostly tough-jawed and firm even though the show’s label copy notes a friend once described him looking like a “sad bulldog.”

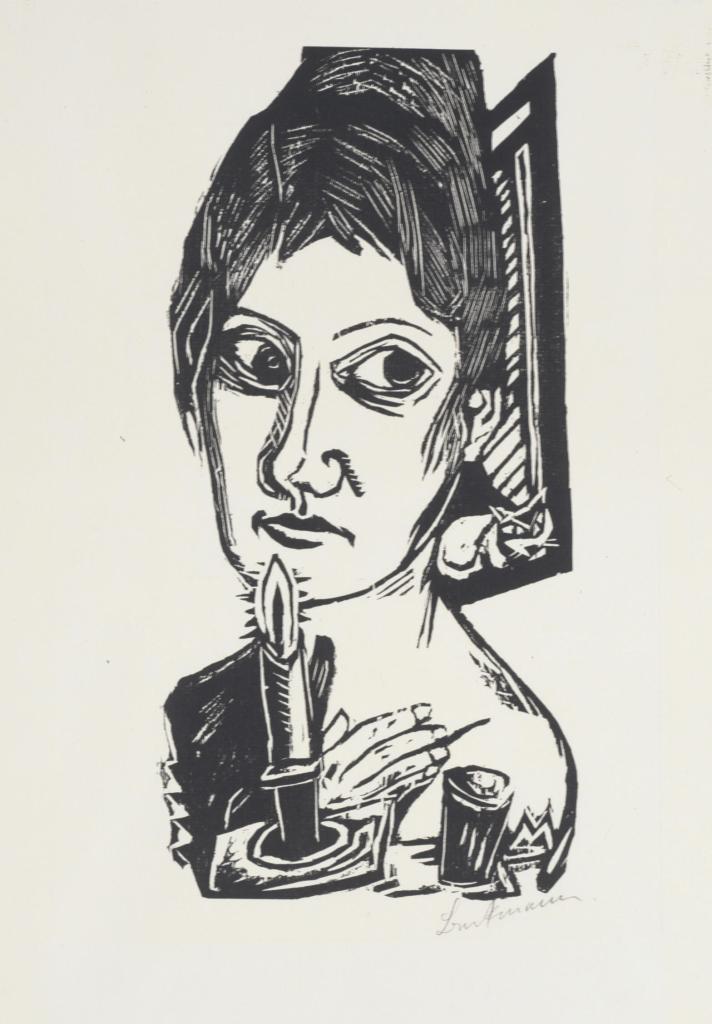

Beckmann’s “Smoker” is a small and densely brilliant gem with smoke rings on and around his face. A woodcut self-portrait (also at Maasch) shows him tough, confident and intense. A hilariously disturbing exception is the self-portrait for the 1919 portfolio “Hell,” in which he appears manically clownish.

Beckmann often presents society as chaotically impenetrable and peopled by a grotesquely self-indulgent bourgeoisie masquerading as decent folk. The flip side comprises the (mostly) sympathetic images of performers. Beckmann seems more comfortable with people who acknowledge their costumes and role-playing.

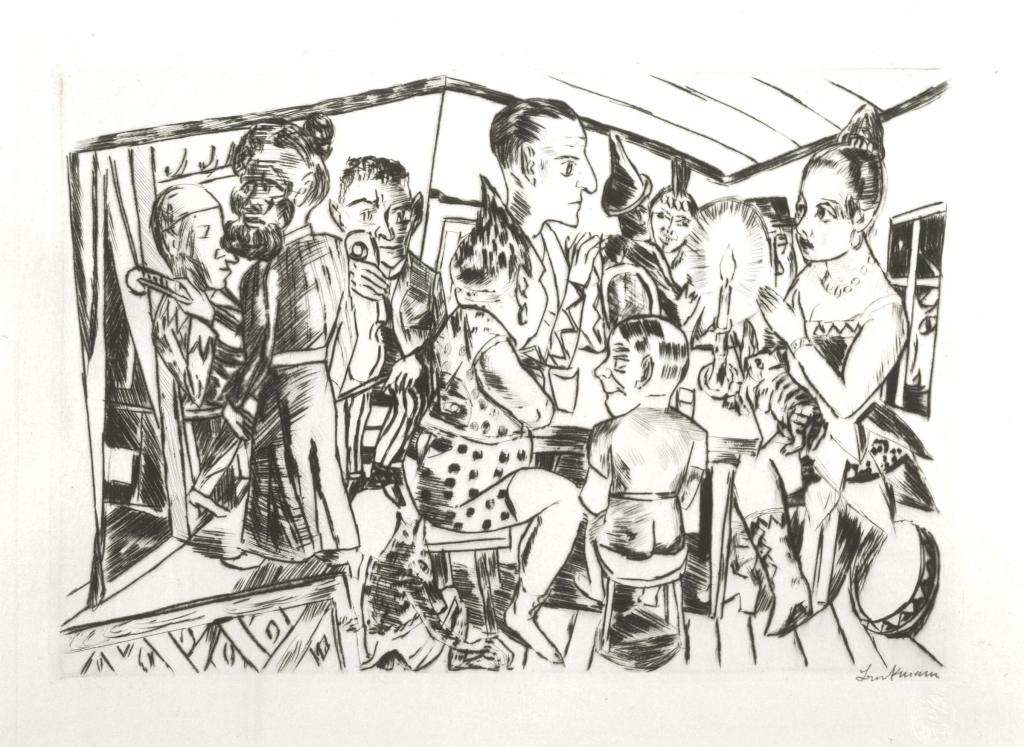

“Behind the Scenes” shows a group of performers backstage. Their repose is comfortable even though the room is rendered with a folded, zigzag perspective. They rest and talk. A pretty dancer sits before a candle stroking a cat. A cow peeks in the window (a nod to Chagall?). Together, these performers share a bit of sanctuary from the crazy world.

One wall of “Modernism and Masquerade” features four prints: intoxicated drinkers, a New Year’s party, “Society” and a scene from an asylum. Each shows a group of grotesque people uncomfortably squashed into a scene writhing with irrational complexity. The labels of the four could be mixed up without changing their meaning. Beckmann’s wit can be powerfully brutal.

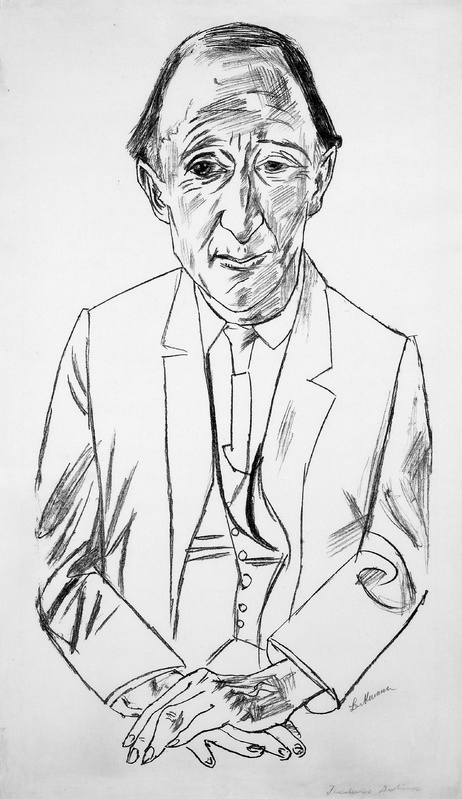

Yet, one of my favorite works at the PMA is an unusually calm and affable portrait of composer Frederick Delius on loan from Edward T. Pollack Fine Arts. Pollack’s gallery (just two blocks from the museum) is currently featuring a fine exhibition of German Expressionist prints by Beckmann’s colleagues and contemporaries.

Beckmann is mostly known as a painter, but his 300 prints are a major component of his expanding reputation. While his paintings are often intentionally impenetrable, Beckmann’s prints offer a scalable window into a world of brilliant and often biting insight and commentary.

These shows should not be missed.

Freelance writer Daniel Kany is an art historian who lives in Cumberland. He can be contacted at:

dankany@gmail.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.