“The Odyssey” is a Greek epic about Odysseus’ trek home after the Trojan War. The flip side of the story is about Penelope, the hero’s wife and mother of their son, who was just a month old when Odysseus left.

Faithful Penelope thwarts the scores of suitors insisting she remarry by saying she will choose a new husband when she finishes weaving a burial shroud for Odysseus’ father. Cunning Penelope weaves by day and yet undoes her work by night – buying time until Odysseus returns 20 years later.

Judith Allen-Efstathiou’s exhibition, “Here and There,” at Whitney Art Works brings Penelope’s story to mind for many reasons. The artist splits her time between Greece and Maine, and the show is about historical journey, women making textiles by hand and the difference made by perspective.

Although Allen-Efstathiou grapples directly with decorative aesthetics, her works greet the viewer with a coolly intellectual presentation. Most are lightly rendered drawings on paper – flat and devoid of representational space.

While the lack of traditional genre, space, subjects or rendering can be intimidating, this type of work is Whitney’s strong point, so I was not surprised when Allen-Efstathiou’s work came into focus for me as smartly insightful and appealingly open-ended.

“Here and There” divides itself loosely into three bodies of work.

The back gallery features a series of small (and pleasantly dense) paintings and drawings focused on the idea of the home as a vessel – a fixed point through which people and memories flow.

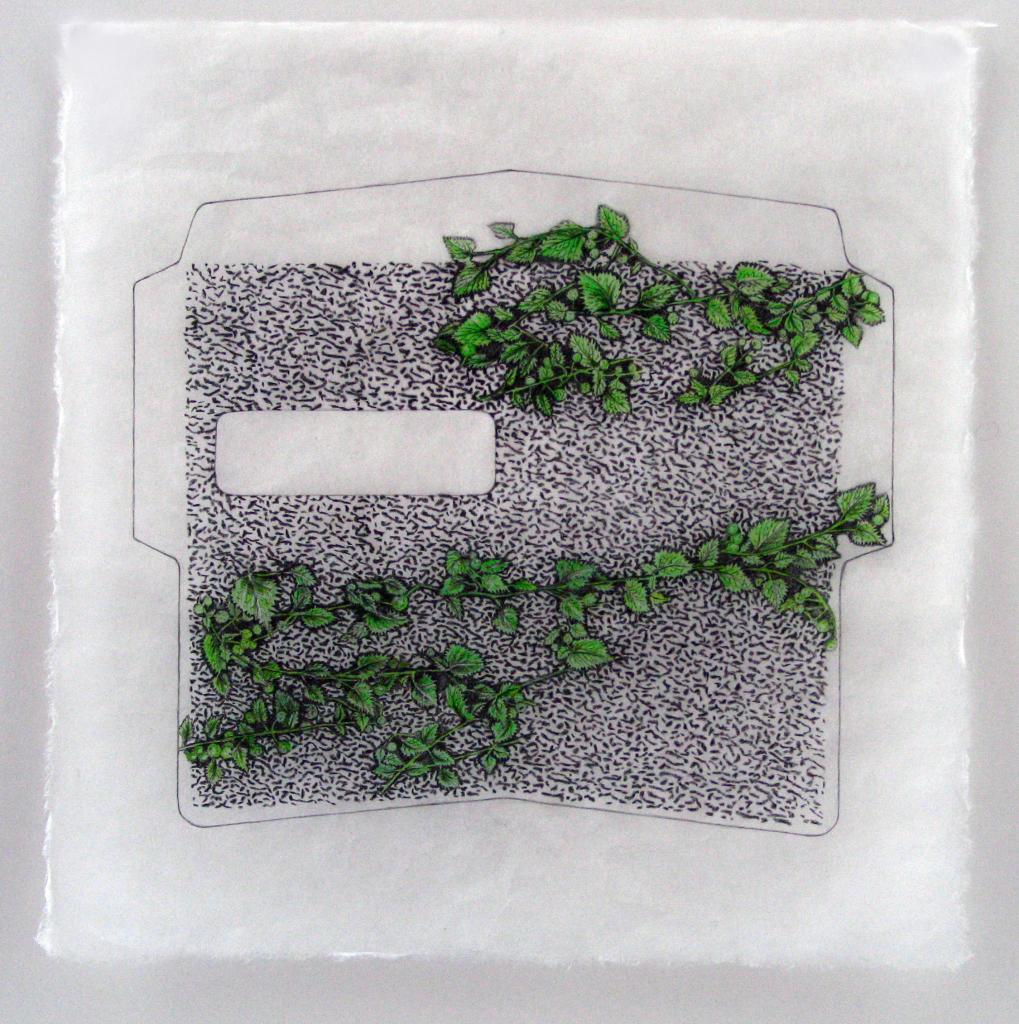

Ten of the works in the front gallery are based on security envelopes, the kind with a seemingly arbitrary pattern printed on the inside so the contents can’t be read until opened. Several are drawn as though unfurled, and woven into the pattern are traditional healing herbs. They are harbingers of bad news softened or remedied.

Allen-Efstathiou’s other works are about textiles and botanical forms. Most are drawings that emulate or mirror needlepoint and weaving patterns. Her work with pencil reveals she is a strong draftsman as well as a contemporary artist deeply dedicated to process.

Two drawings (both titled “Binary is Best”) are draped in the middle of the gallery. Each is 15 feet long and 25 inches wide. On one side is a decorative drawing of thistles or other healing herbs in the style of a needlepoint grid. On the other side, matching forms are rendered in the “0”s and “1”s of binary code.

So many associations immediately come to mind that I could see 20 viewers understanding the same work in 20 different ways: the use of pattern in computer code and weaving; traditional versus mechanized looms; symbolism versus ornament; pixilation in old versus new technologies; decoration versus function; tradition versus the new; and so on.

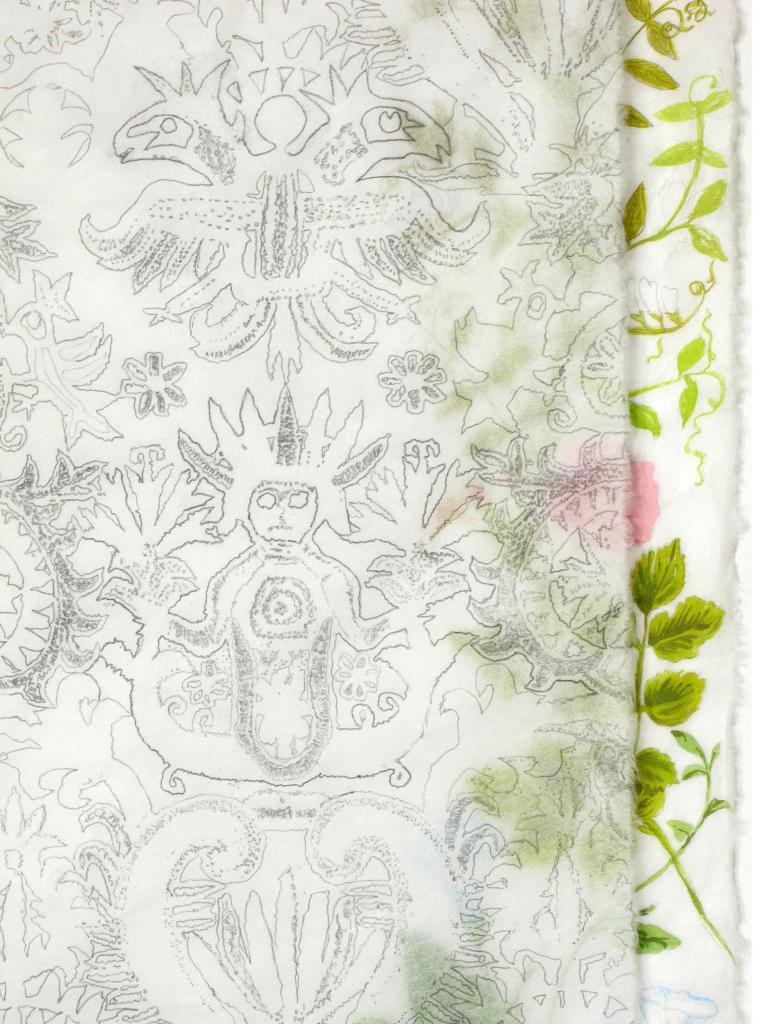

One of my favorite pieces is “Mermaids with Flowers.” It comprises drawings on two pieces of softly translucent mulberry paper – one, smaller, hung over the other. The decorative patterns (some colored beautifully with gouache) of the larger piece are only completely visible in the margins.

The metaphor of marginalization is handled by Allen-Efstathiou with commendable strength and clarity. She approaches many other works in the show similarly, such as drawings based on elements of their decorative frames.

Other pieces on paper or fiber allow the top layer to interact with those underneath, revealing how the bottom layers, though obscured, often play a broader foundational or organizational role.

I enjoy thinking about Allen-Efstathiou’s works in terms of feminism, which in the arts is fundamentally about an alternative viewpoint. Penelope and Odysseus, for example, share the same story – while the husband is off to war and adventure, the faithful wife faces her own tribulations at home.

Some of the fabric pieces were actually made by Greek women who are literally cloistered: they are using the money to enhance their dowries. Others were stitched by women in Greek prisons.

Even the title “Here and There” plays to the idea of the self and an Other. It is a complementary pair, but not equal. In this sense, I get the feeling Allen-Efstathiou is making some powerful political assertions, but she is doing so without whining about – or to – that Other.

She makes a very beautiful, compelling and appealing case that perspective matters.

Freelance writer Daniel Kany is an art historian who lives in Cumberland. He can be contacted at:

dankany@gmail.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.