CAP HAITIEN, Haiti – The pickup jostled through craters in the dirt road, pushing farther into Petite Anse, a packed collection of tin shacks, squat cinder block homes and abandoned trucks on the outskirts of Cap Haitien.

The three women in the back climbed out as it stopped and headed down one long dirt path, toward an opening piled with mound after mound of densely compacted garbage.

They are part of a team of outreach workers who go into Cap Haitien’s poorest slums, working out of a health clinic at Fort Saint Michel and funded by Konbit Sante, a Portland-based nonprofit.

The clinic is one of only two that serve the devastatingly poor neighborhoods bordering Cap Haitien, offering maternity care, tuberculosis testing and treatment, prenatal care, emergency care and other services.

Traveling Wednesday into Petite Anse, which is built on refuse, the women walked across a causeway built up with old tires, dirt and trash that held back the fecal-contaminated pools of stagnant water.

There’s no stench, oddly. Recent floods that temporarily forced the poorest of the poor out of their homes also washed out the ripest garbage.

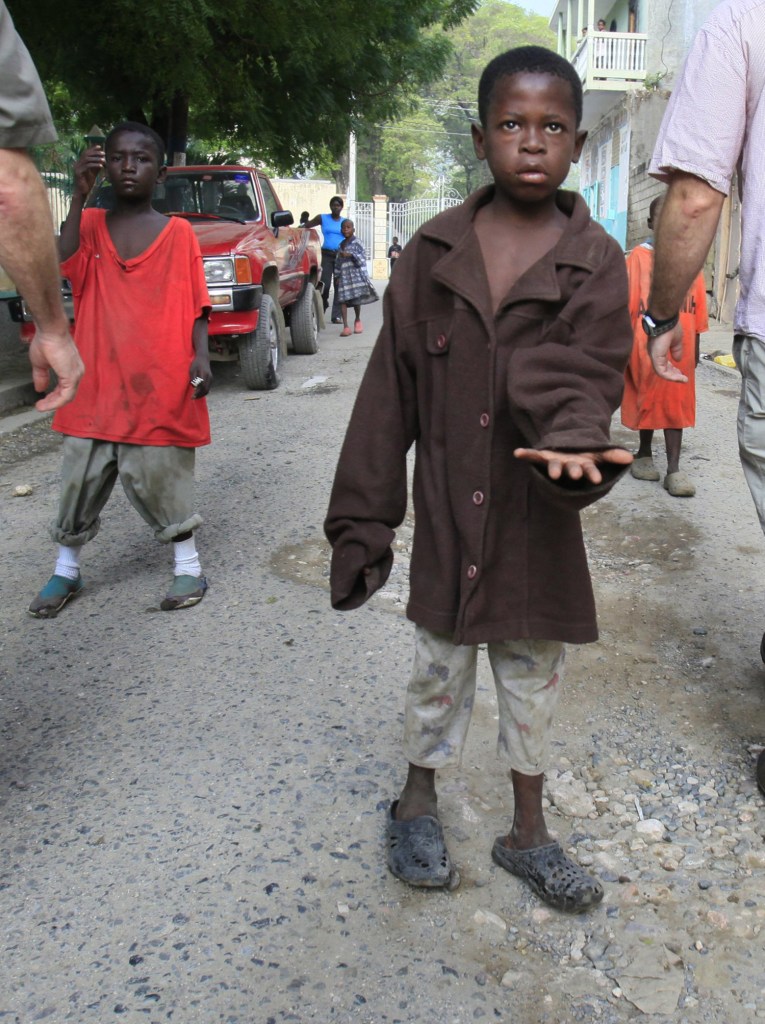

As they walked, a group of little children ran along behind, calling out ”mange, mange, mange” – ”eat, eat, eat.”

They showed their bellies – they were hungry.

The women abruptly turned a corner into the entry of a small home, where they met Mamyvon Rosannie. She was part of a class for new mothers, and the women wanted to visit her, to see how she and her baby, Jean Yves, were doing after the floods.

Smiling, she reached into the hut and pulled out a naked, fat little 4-month-old boy, bouncing him up and down as he looked curiously at the women.

”It’s the reward – the prize – when you see someone like that,” said Dr. Youseline Telemaque, obstetrician-gynecologist.

Telemaque and the other two women, health outreach worker Mansenat Goaciagia and her supervisor, Miguelle Antenor, are all funded by Konbit Sante, which has been working for a decade to help improve the health systems in Cap Haitien.

Konbit Sante initially began work at the Justinian Hospital, and expanded to a health clinic in the Fort Saint Michel neighborhood in 2003.

”All of us came to realize that the hospital’s impact, in terms of the health status on the community, is really limited to the extent it’s related to the community,” said Nate Nickerson, executive director of Konbit Sante. ”We wanted to look outside the hospital.”

The clinic is based in that poor neighborhood, but through its eight community health workers, Konbit Sante reached out into several of the slums, including Petite Anse. The slum neighborhoods are next to each other, separated by roads, rivers and other dividers.

As she walked amid the hovels, residents called out to Goaciagia, ”Hey Noola!”

”Hey, OK!,” she called back.

She’s responsible for the Petite Anse neighborhood, where about 10,000 people live. Konbit Sante’s outreach workers check on women after they have given birth, vaccinate the children and get the mothers into a class that teaches them everything from hygiene to the importance of exclusively breast-feeding their babies.

”It’s too much for one person,” said Telemaque.

Without Konbit Sante, what help would these new mothers get?

”Nothing,” she said.

Telemaque helps organize group vaccinations in the neighborhoods, and works with midwives who help women who can’t get to the clinic or Justinian Hospital. She has worked with about 80 midwives, teaching them about complications, and when it’s important to get the mother to a health care facility. Telemaque works at both the clinic and Justinian.

”She’s doing amazing work reaching out to the traditional midwives,” said Nickerson.

But it takes its toll.

In August, she wanted to leave Konbit Sante, Telemaque said. One of her patients couldn’t scrape up the 10 goude she needed to catch a tap-tap cab to the clinic and died at home of birth complications. Ten goude is about 25 cents.

”She died, only for that,” Telemaque said.

The endless struggle against unfathomable poverty – one mother at a time, one TB patient at a time – just wore her down. The other health professionals at Konbit Sante talked to her, helped her.

”They said ‘We do something this little to do something big,”’ she recalled.

Between 200 and 300 people come through the clinic daily, said Telemaque. The need is great, Nickerson said.

With a mountain of needs, how do the staff members at Konbit Sante feel that they’re doing something that makes a difference?

”It’s not about us feeling we’re doing something. It’s not about us. It’s about, in the end, the impact,” Nickerson said.

People are being found with tuberculosis and getting treatment. Women are having safer births. Babies are fat and happy and bouncing, even in the middle of a garbage dump, because of the work Konbit Sante continues to do.

”We never wanted to be medical tourists,” said Nickerson. ”We want to be genuine partners with other human beings who are really struggling.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.