Commercial contractors in southern Maine say they are having trouble hiring experienced construction workers because many have fled for better-paying jobs outside the state.

Their departure, prompted in part by years of relatively little new construction in Maine, has made it harder to revive the industry now that more private and public interests are building projects again. The labor shortage also has suppressed competitive bidding in Maine and caused the delay of several projects.

Matthew Marks, CEO of the Associated General Contractors of Maine, a trade organization that represents 180 member companies, said the problem began two recessions ago in 2000, when construction in Maine reached a peak, followed by a sharp decline.

“We lost a ton of talent – 10,000 people out the door,” Marks said. “Those are the people that would have been training the modern workforce. They left.”

The problem worsened during the Great Recession that began in December 2007 and prompted many Maine contractors to downsize, consolidate with other firms or shut down completely, he said. Thousands of workers lost their jobs or were unable to find enough work to sustain their households in Maine.

According to Maine Department of Labor data, there were 5,171 specialty contractors in the state at the end of 2001. There were 3,389 by the end of 2015, a 34 percent decline.

At the time of the recent recession, commercial construction workers in Maine were making an average of about $45,000 a year, Marks said, so the exodus was driven by a lack of work, and not by low pay.

“I know people that have told us we lost a good portion of our people to the Boston market,” Marks said. “People have to feed their family at the end of the day. They have to keep a roof over their head.”

PAY TOO LOW TO LURE BACK WORKERS

Now that southern Maine is experiencing a resurgence of private-sector construction – including new hotels, condominiums and senior housing – it may be nearly impossible to lure back those skilled workers.

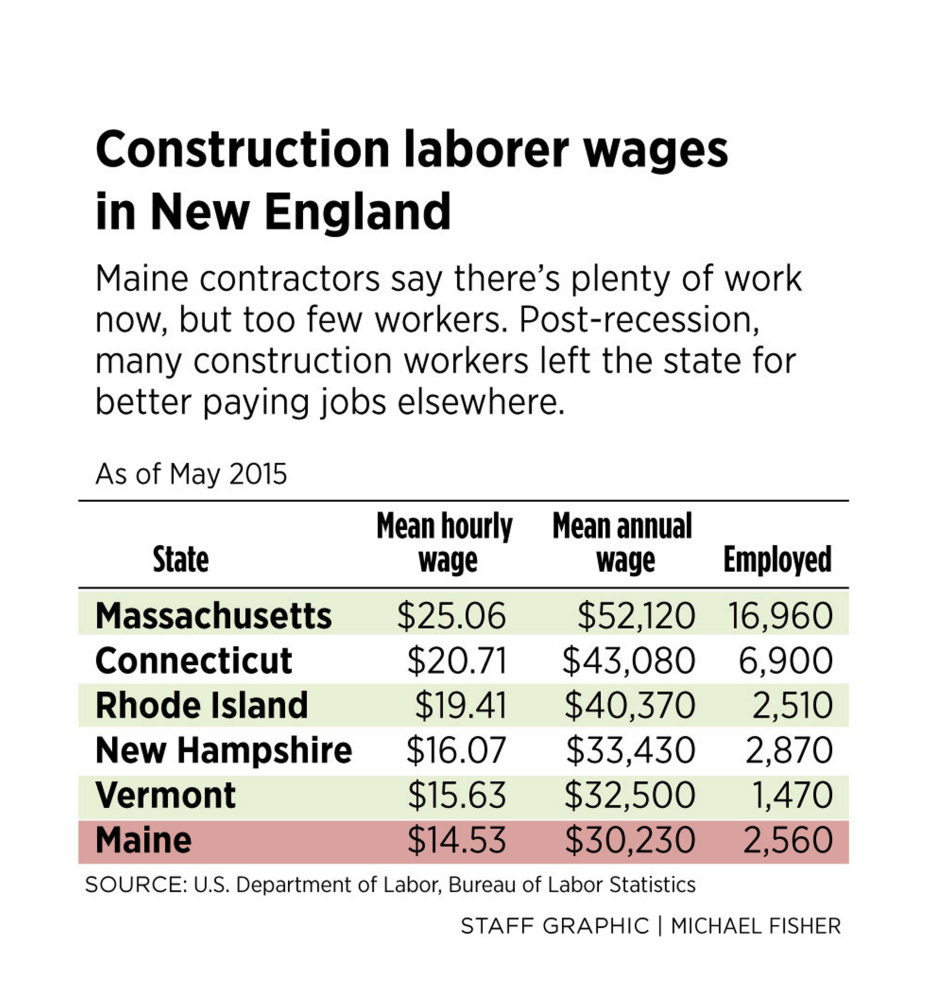

One reason is the significant difference in pay. As of May 2015, the mean hourly wage for construction laborers in Maine was $14.53, or $30,230 a year, the lowest in New England and 42 percent lower than the mean hourly wage of $25.06, or $52,120 a year, in Massachusetts, according to the U.S. Department of Labor’s Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Another issue is the reluctance of Maine construction companies to hire more full-time staff, even though the industry is recovering, Marks said.

“There is a sentiment out there of, ‘What will happen if there’s another downturn in the future? How many people should we bring on?’ ” he said. “Nobody likes to lay people off.”

The problem is occurring nationally as well. Construction employment totaled 6.7 million workers in April, the highest level since December 2008, but still isn’t sufficient to meet demand, said Ken Simonson, chief economist for Associated General Contractors of America. Although the association is seeing more construction spending, there is also a worsening worker shortage, which prompted the association to launch a new online job portal this month.

“Reports from contractors and recent Census Bureau data on construction spending through March suggest industry demand for workers will remain robust, if firms can find employees with the right skills,” Simonson said in a news release.

One consequence of the subcontractor shortage is that construction clients are receiving fewer competitive bids, and are likely paying more as a result.

In April, the deadline passed for competitive bids on the $100.2 million Sanford High School and Regional Technical Center, considered the most expensive project of its type in Maine’s history.

Seven general contractors pre-qualified to bid on the project. The district received only two bids, and it ultimately awarded the master contract to an out-of-state firm, New Hampshire-based Hutter Construction. A Maine company, Gorham-based Shaw Brothers Construction, won a $14.1 million contract to perform all of the pre-construction preparatory work on the 127-acre project site.

District Superintendent David Theoharides said he has been told that one reason more companies didn’t bid is a state requirement that the winning contractor pay a $12,000 penalty for every day the project goes past its Aug. 1, 2018, completion deadline. There was a concern that difficulty finding subcontractors could lead to delays and missing the deadline.

The district also received a paucity of bids on other components of the project. For instance, it received only a single bid for drywall installation, Theoharides said.

“I think the subcontractor on the drywall knew they were the only one, because boy did they come in high (with their bid),” he said.

Consigli Construction Co. in Portland is one of the general contractors that was pre-qualified to bid on the Sanford school and ultimately decided against it.

Matt Tonello, project executive and operations manager at the firm’s Portland office, said one reason was a concern that the lack of competitive bidding by subcontractors could delay the project’s completion, thus invoking the daily penalties.

Tonello said that about 85 percent of the work awarded to a general contractor is carried out by subcontractors, some of whom will make $5-$15 more per hour on projects in Massachusetts. Lately, a subcontractor bidding process that might normally take less than three weeks has been taking more than twice as long, he said. In some cases, the company doesn’t receive any bids initially, and it then has to call subcontractors repeatedly and cajole them into submitting a bid or extend the search area farther out, Tonello said.

“We’re not getting bids by our deadlines, pretty consistently,” he said.

The price of subcontractor labor has been rising as a result of the increased demand for their work, Tonello said, but so far, low prices on commodities such as fuel and steel have made it possible for general contractors to continue bidding at roughly the same overall price.

However, that only holds true as long as commodity prices remain low, he said.

“If we see commodity prices increasing, that’s going to compound the problem,” Tonello said.

NO FLEXIBILITY TO RAISE PRICES, WAGES

So why don’t general contractors simply raise their prices and pay everybody more? Tonello said the reason is that in Maine, developers are already paying about as much as they can afford while still allowing their hotels and other commercial projects to be viable. If the cost of construction went up significantly, they might stop building, he said.

Tonello noted that even at the current costs, certain project types such as office buildings aren’t being built. He said the situation isn’t likely to change unless Maine markets such as Portland begin to see an influx of new demand.

“I don’t see this market changing significantly unless we see employer growth,” he said.

Marks said it is worth mentioning that the labor shortage is in some ways a positive sign. It means that there is growth happening in Maine, things are being built and people are being put to work. He said it would help if more Maine schools encouraged students to pursue careers in various skilled trades, which can and do provide plenty of work at decent pay. For example, the mean annual salary in Maine as of May 2015 was $41,580 for brickmasons and blockmasons, $48,240 for electricians, and $48,780 for plumbers, pipefitters and steamfitters, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

“We have to get people trained, and we have to do it fast,” Marks said. “It’s a good problem to have.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.